Editor’s Note: Many of our students in ACU Biology Research work in teams composed of members with differing levels of experience. This blog was composed through a collaboration by Samantha Studvick (2nd year) and Kathy Le (1st semester) working together on the same research project.

Sam: I began doing research with Dr. (Josh) Brokaw at the end of the Fall 2015 semester. Initially, I was on one of the Thomasomys phylogeny projects, specifically the CO1 (Cytochrome c oxidase I) group collecting mitochondrial DNA sequences. I worked on this research for all of the Spring 2016 semester, and I got to present at the ACU Research Festival and the Texas Academy of Science and Society for the Study of Evolution conferences.

Since I enrolled in the Biology Research course this semester, I began a new project expanding on the DNA sequencing skills that I had already learned. I was a little nervous, not only to be working on an unfamiliar project, but to be working on a completely new project in a newly formed lab team. Drs. Brokaw and (Diana) Flanagan created a new research group, under the direction of Dr. (Jennifer) Huddleston, for a project to identify a set of unknown cave bacteria based on phylogenetic reconstructions.

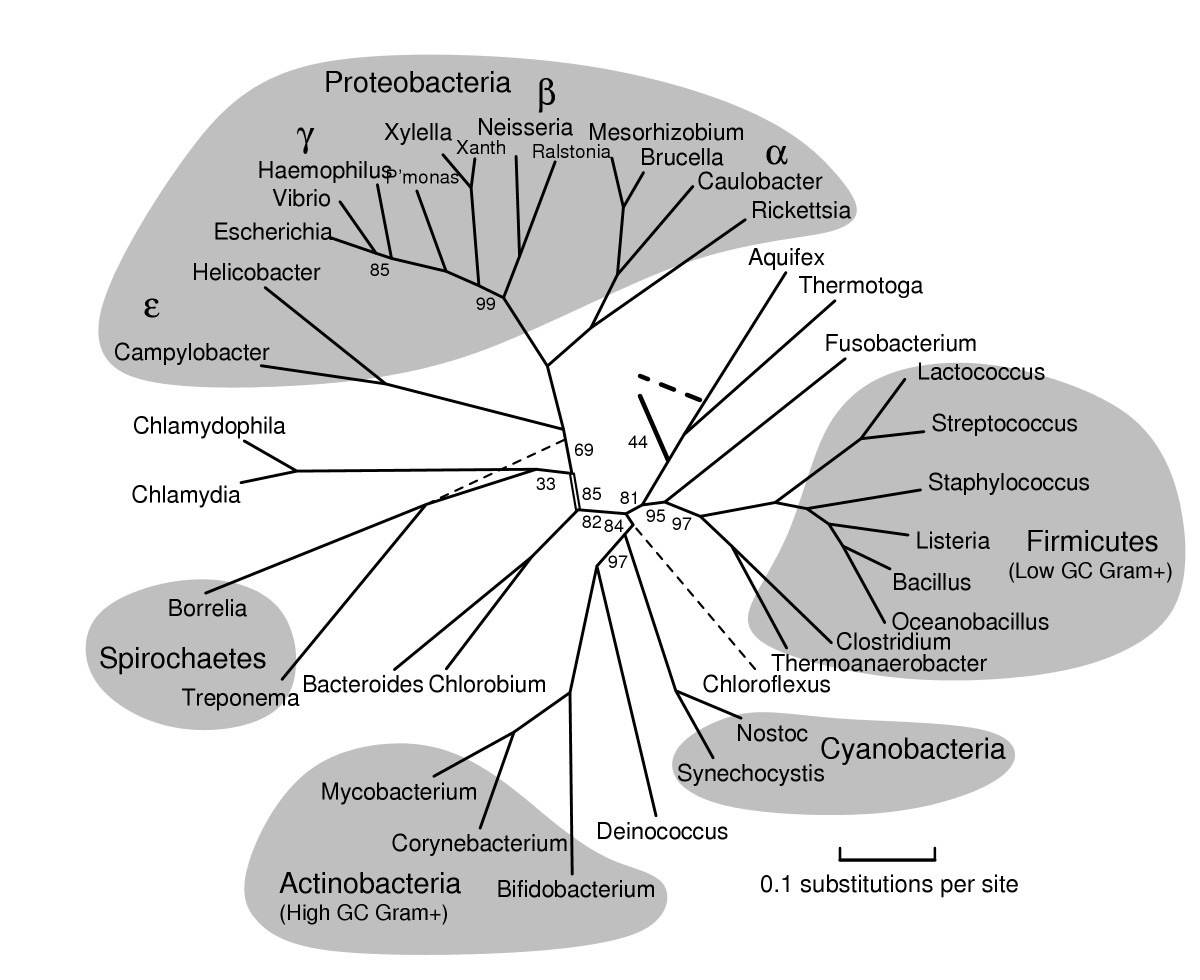

Example phylogeny of Domain Bacteria from BMC Evolutionary Biology 2005, 5:34

A phylogenetic tree demonstrates the interspecific relationships between organisms (like a genealogy of species). Most phylogenies are based on DNA sequences, and this requires a complex process of DNA extraction, PCR (DNA replication), gel electrophoresis, DNA purification, DNA sequencing and alignment, and computer analyses. While the goal of the project was to begin identification, most of the semester was devoted to finding the correct method for DNA extraction and running the PCR.

Kathy: In the fall of 2016, my sophomore year, I began my first semester of research with Dr. Brokaw. We did PCRs and ran gel electrophoresis data on bacterial cave swabbings done in Terrell County’s Sorcerer’s Cave (notably the deepest cave in Texas) with the goal of identifying the bacteria in this unique isolated environment.

Overall, we used three separate methods of extracting and replicating DNA because the DNA collected was not always able to produce bands. Even though much of this semester was devoted to finding a successful technique, I learned a lot about the processes behind running PCRs and gels. It’s quite interesting seeing something you learn about in a Gen Bio lecture class actually happen in the flesh. It makes concepts easier to understand because there is tangible evidence and processes that occur to support the concepts. For instance, the process of synthesizing and denaturing DNA. Eventually, we have enough to run a gel, since the DNA is copied to more than a billion times. Once this has occurred, we run the gel and search the sequence in Genbank to begin to identify the species of the bacterium.

Sam: We first tried to transfer portions of bacteria colonies directly into the PCR tubes without DNA extraction followed by the basic PCR protocol. The results were unsuccessful, so we implemented a new strategy for DNA extraction. Again, the results were not really worthwhile. After altering some of the quantities for the master mix (combined chemicals used in PCR), we were able to get some results, albeit inconsistent. With the DNA isolated and amplified by our successful PCRs, we were able to identify three of the isolates as Pseudomonas, which gives us a starting point for next semester; however, we will likely be switching our DNA extraction/PCR protocol yet again to hopefully yield more successful and consistent findings.

Kathy: Initially, it was a tough semester since I was coming in totally uninformed. I constantly had to learn as we went, continuing to ask questions about the protocol and materials used for PCR prep and gel-running. Gradually, I got the hang of it, as I’m sure everyone else who was a seasoned researcher in the lab had, since the research is basically student-run with supervision from their research advisors. My main goal was to just learn how to do the process and then become good at it. Seeing as we were failing to have bands on our gels, it was a bit discouraging to say the least. I felt that I was doing the procedure wrong or perhaps botching it on the filling of the wells in the agarose. We plan to correct this by using DNA extraction kits next semester to increase the likelihood of bacteria identification.

Sam: Doing research can be a frustrating process at times, especially with ineffective protocol. Nonetheless, I really do enjoy conducting research with a team. As a hopeful Pre-Med student, this research is not directly related to my intended field; however, there are some implications as this project may begin to look into the development of antibiotic resistance (in a distant future). The techniques used in the lab are invaluable resources, though, and are important for a foundation in any topic of research. Being concurrently enrolled in Microbiology (lecture and lab) has broadened my appreciation of the study of bacteria. Moving forward, I am excited to continue working on this project, and I look forward to presenting my findings at various conferences.

Preparing bacteria for PCR for the last time in the Clark Stevens Lab.