Reflection on Teaching

According to the Abilene Christian University Faculty Handbook:

The effective instruction of students is the primary purpose of the university and is expected of every faculty member. Applicants must include reflection on their teaching effectiveness. The generally recognized qualities of effective teaching are:

-

- Self-Reflection and Improvement

- Integration of Faith and Learning

- Knowledge of the Subject Matter

- Ability to Communicate

- Interest in the Student

- Reflection on Student Evaluations

- Self-Reflection and Improvement

1. Self Reflection and Improvement

“The teacher should constantly work to improve courses, experiment with new materials and methods of delivery, and keep current with the subject matter.”

— ACU Faculty Handbook

1. TEACHING PHILOSOPHY

2. TEACHING INNOVATIONS

3. SELF-REFLECTION & IMPROVEMENT

TEACHING PHILOSOPHY

1. Teaching Philosophy

The best lessons in life do not simply alter what we know, they transform how we know by reframing our taken-for-granted understandings of the world and inviting us to consider questions that are beyond our current vision. The best teachers challenge us to see a world bigger than ourselves as they equip us with the ability to use our imaginations and invite us to participate in community with others. As a teacher, my favorite lessons are the ones that ask challenging questions and require imaginative and critical thinking. In my first years of teaching, I focused too heavily on lecturing and failed to leave room for discussion. Since coming to ACU and discovering active learning strategies in Adams Center workshops, I have cultivated teaching methods that are more strategically designed, require more thoughtful reflection, and are much more collaborative, driving students to be better critical and creative thinkers.

A Problem-Based Approach

My favorite method for encouraging thought-provoking conversation is to utilize problem-based teaching. By presenting learners with complex dilemmas full of ambiguity and conflicting interests, I am able to challenge my students to take a stand on an issue or formulate a solution and defend their positions. Problem-based learning stimulates them on several levels. First, it requires them to make difficult judgments. The way we weigh our choices reveals the underlying systems of meaning that we draw from in our daily lives. Attempting to answer challenging problems, whether hypothetical or real, exposes these systems and uncovers the substructures of our beliefs. Second, problem-based teaching digs deeper by making students justify their positions. Such digging leads to deeper learning because as students defend their ideas, opportunities emerge for them to integrate the course content (readings, lectures, and discussions) into their responses. Finally, problem-based learning helps students make connections between their studies and their own personal narratives. When knowledge is practical and connected to our personal identities, it comes to life in the real world and gains more meaning.

Most of my art classes utilize this approach. For example, in 2D Design, one of the first exercises given to students creates a design problem by establishing arbitrary limitations that the student must work within. In the assignment, students are challenged to compose a visual design that explores the complexity of different characteristics of shapes to convey a concept by only using four rectangles and a circle. In the assignment, they are given a worksheet with sixteen artboards. The sixteen artboards are arranged in four by four columns with each column housing four differently shaped artboards (vertical rectangle, horizontal rectangle, square, and circle). Students are given theme words for each column and asked to represent the concept of the theme in four variations on each of the different artboards. By establishing the arbitrary boundaries for the assignment, I have created a unique problem that challenges them to dig deeper and draw connections between different elements of art and principles of design. Below is an example of one student’s response to this assignment.

Project-Based Learning

Learning in Community

A third philosophy that underpins my teaching is the belief that students learn best when they are in community with one another. Challenging students to work together invites interdisciplinary dialogues, demands teamwork, and can lead to important relationships with different-minded people. One advantage of group work is that it holds all students accountable to someone other than the instructor for their work by providing them with additional social incentives for the learning process. Another benefit is that it strengthens the network of connectivity among students in the classroom, cultivating a better learning environment. Group work in my classes can take many forms. From table discussions to semester-long projects, I try to include some component of collaborative learning in every class meeting.

One example of collaborative learning in my classes can be seen in the Topic Expert Group Presentation assignment I require in my Art History General Survey courses. In this assignment, randomly generated groups are asked to speak to the class as “experts” on a topic related to the class, but not explicitly included in the course materials. Topics include: death in art, the art of religion, copies vs. originals, iconoclasm, and functional art.

INNOVATIVE TEACHING

2. Innovative Teaching Methods

Innovation, by definition, is a process of refining ideas to develop better solutions. To understand what a better solution is, we must first decide what “better” is. In the classroom, better can mean a lot of things. For some it means more student engagement, for others it means more content, often for (some of) my students it simply means less work. This makes “better” somewhat of a moving target. But, according to Bloom’s taxonomy, better learning comes about through the engagement of higher forms of thinking that go beyond merely remembering facts. Instead, deep learning engages students’ higher faculties through application, analysis, evaluation, and creative generation. Thus, to innovate in the classroom essentially comes down to finding strategies that require intimate engagement with their subjects and creative and critical thinking.

Design Thinking

Design Thinking (DT) is emerging as a leading collaborative method for generating innovative ideas (Glen, Suciu, & Baughn, 2012). By embracing interdisciplinary collaboration, promoting empathetic listening, and encouraging iterative, exploratory processes, DT is a method of discovery that has the capacity to cultivate lateral thinking in multiple contexts (Cruickshank, 2012). Although most of its literature has primarily focused on its commercial potential for businesses, Design Thinking is now receiving greater attention as a pedagogical instrument, artistic ideation tool, and research method (Seidel & Fixson, 2013).

DT is, at its most fundamental level, a collaborative, divergent process for solving “wicked” problems (problems without one clear solution). Unlike analytical thinking, which relies predominantly on convergent processes to examine data and converge on a single solution to a specific problem, DT utilizes divergent methods that rapidly generate multiple possible solutions in order to “build up” rather than “break down” ideas into specific components (Baeck and Gremett; Waloszek; Hicks 393).

DT is a loose canonization of steps that has been popularized in recent years, most notably by the design firm IDEO and the Stanford d. school. Most DT methodologies have around 5 to 7 stages: understanding the problem, observing users, interpreting results, generating ideas, rapid prototyping and experimentation, testing, and iteration.

In my classroom, students have used DT to tackle major social problems, such as addressing the problem of food deserts in Abilene in a course on Human Identity and Community, considering traffic problems in an Honors Colloquium on the methodology, designing an orthotic support for a three-legged dog in collaboration with the Maker Lab, and building paper towers in Cornerstone. My favorite of these has been the incorporation of DT into the Human Identity and Community course.

In this course, we typically spent the first two-thirds of the semester discussing the topic of justice, exploring the different perspectives on the issue (largely through case studies), and challenging students to take stances on the approaches to the just community that they find most persuasive. In the closing weeks of the semester, I wanted to find a way for students to practically apply the theories we had discussed to real world issues.

We began by having students select a “wicked” problem related to justice in Abilene (see assignment description). Then, we took them through the DT process, step-by-step, using a project workbook. As students engaged in the processes of practicing empathy, defining the problem, brainstorming ideas, prototyping solutions, testing and failing, and iterating new ideas they were able to move from analysis to design—from formal, rigid intellectual examination to informal, divergent idea generation. As a result, learning moved from theory to practice and students saw the complexities of justice in action.

One of my favorite ideas was a concept students developed for a ride hailing app (like Uber) for university students to drive other students to the store or to share rides on trips out of town. The project, called “Shotgun” (referring to the common expression “riding shotgun,”) started because many students in the group were from international locations and were limited in their ability to travel off-campus because they did not have a vehicle. As the students engaged in the initial brainstorming, the international students communicated this concern and, taking a position of empathy, the non-international students who had vehicles mentioned that they would not have any problem giving rides to students if they only knew the students needed a ride. The initial idea was to use social media to communicate this with other students.

Eventually, the idea emerged to create an app that a student with a vehicle would use to communicate that she or he was going off-campus. It would give details about the location the driver was visiting, how long they would be there, what time they were leaving, how many people would fit in the car, and where to meet. Riders would then sign up. As they dug deeper, interviewing students and campus officials, the group realized that what they thought was a relatively simple solution required more thought. Liabilities were a concern. What if a driver had to leave and left some riders behind? Would there be background checks on drivers? Would there be a way for riders to “tip” drivers or help them pay for gas through the app? What if there was an accident?

The students created prototypes of an app and developed different business models, digging in as deeply as they could in the time provided. Overall, even though the app itself was never developed, the project was a great success. Through the assignment and subsequent reflection on it , students were able to see the many challenges that underlie issues of justice on campus. They recognized that there was an inequity in the experience of students without vehicles (engaging in empathy), saw that there were multiple possible solutions (wicked problems), experienced the joys of a great idea met by the frustrations of not being able to bring that idea to fruition, and worked collaboratively with others to hear out ideas and explore solutions.

Forgery Assignment

The act of creating something helps pull disparate elements together into a functional and coherent whole (Bowen 2012, p. 81). Creation requires imagination, exploration, composition, and revision, not to mention synthesis. Art history is a course that is mired in analysis and evaluation. All throughout the semester students present or are presented with artworks that they analyze formally, symbolically, and contextually, so that by then end of the course they have established a system (even if a somewhat rudimentary one) for analyzing and evaluating artworks. The system works, but I always felt that something more was missing from the course.

Starting in the Spring of 2016, I began experimenting with a new approach to teaching art history. The major change came about by giving my students the opportunity to forge the work of a master artist in lieu of writing a traditional research paper. Since the work is a forgery, students are not allowed to simply copy an existing work of their selected artist, but instead, they are required to create a work “in the style of” a great artist.

In the assignment, they choose everything from the subject to the medium to the color palette and technique, in an attempt to imitate, as closely as possible, the methods and processes of the master. They have the rich opportunity to go as deep as possible, learning as much as they can about an artist and her or his artwork. The results are often outstanding. In the years since I started this assignment, I have had students purchase and grind their own pigments (since modern paints are made with different chemical compounds than 16th or 17th century paintings), purchase old books and cut the flyleafs out to have authentic, weathered paper from the era of the forgery on which they typed their historical provenance for the piece using an antique typewriter, and I even had one student bake their work at a low temperature in an oven to enhance the effect of aging.

The greatest value of this assignment is that it creates space for both hands-on practice and generative learning. Generative learning goes beyond hands-on copying because it requires the students to generate their own content and the bar for the assignment is as high as the student sets it. Not all students are required to do the forgery. Some choose the route of the traditional research paper. However, for a class that is typically composed of Art + Design majors, about half typically opt into this assignment. In the end, it is a win all around. The students work hard on their projects, create something they are proud of, and get to share their work with others. Meanwhile, I have never had so much fun grading.

Top/Left Image: Chera Chaney, 2015, Rachel Ruysch Forgery, “Flower Still Life”

Bottom/Right Image: Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750), 1744, Original Artwork, “Summer Flowers in a Vase”

Low-Stakes Testing

In the spring of 2015, I participated in a semester-long reading group sponsored by the Adams Center. The group was led by Dr. Bob McKelvain and focused on the book Make it Stick. The reading group was a pivotal moment in my teaching career. My experience prior to coming to ACU, as is the case for many other academics, was one in which I received an excellent education in my primary field of study, but very little instruction on teaching or pedagogy. This reading group helped me understand much better how to plan and strategize in my courses to improve student learning and comprehension.

One of the arguments made in Make it Stick is that testing is a foundational component of learning, especially when establishing a base foundation of knowledge. Unfortunately, the most common manner in which we test, especially in Art History, is often through high-stakes, high-pressure examinations that punish or reward students through heavily weighted exam grades. Unfortunately, this approach does not necessarily lead to deeper or better learning than other assessment approaches and can even negatively impact learning for some students. Too often, tests serve merely as dipsticks created to quantify student performance, but do not necessarily encourage learning (Brown et al. 2014, 19).

After teaching art history general survey courses for five years, I recognized that I was not leveraging my assessments properly to enhance the learning experience for my students. To improve my courses, I implemented a system of low-stakes testing.

Before my low-stakes intervention, the objective examination portion of my survey courses consisted of a total of 300 questions administered in a series of high-stakes exams and quizzes. My first intervention altered the exams so that I still administered the same number of questions over the course of the semester, but I now offered students the opportunity to retake the exams and improve their grade.

Since I was increasing the total number of potential exams students could take (since each student could retake earlier tests), I administered the exams using our university’s Learning Management System (LMS), Canvas, which automatically grades objective portions of exams. The exams draw from test banks that contain both artwork memorization assessments and traditional multiple choice and fill-in-the blank questions over readings and lecture subject matter.

I only allow them to retake exams once per five-week period, which forces them to space out their practice after correction. The value of spaced practice is a well-supported concept that has been consistently proven to improve learning and retention (see Cepeda et. al.). I also allow them to see their responses because, as Butler and Roediger have shown, providing corrective feedback greatly enhances the positive benefits of testing, especially when using multiple choice examinations (261).

This new strategy for testing was important for me to implement because research has consistently shown that making errors is an important part of learning (Brown et al. 90). In the past, my assessment procedure focused on an error-free testing methodology (testing that punishes students for making mistakes without providing them with corrective feedback or an incentive to correct erroneous knowledge). There is much new research on learning and assessments that has disproven the effectiveness of our long-established practice of error-free testing (ibid.)

Another strategy I employ, based on Brown et al. is that now I make all of my tests comprehensive. This discourages cramming, as students will need to know the content throughout the entirety of the semester, rather than just the once for the exam.

The new testing method has been very successful. Not only has their performance improved, but through conversations with students I have seen their perspectives on the exams shift. For some students, they see this method as a way to move away from viewing the assessment as a way of punishing students for poor performance toward using assessment as a tool that encourages learning. As one former student, Denver Gravitt, commented, “I love your tests because they combine learning with grace. You don’t just learn the content once then leave and forget it until the final. You have to know it and it sticks with you.” Learning that sticks—that was my goal.

As is true with any assessment process, more refinement is needed. There are definite downsides to this method. For example, a student could cram and show up on the last test day, retake all of her or his exams, and improve a low overall grade to a very high one. Regardless of the system, there will always be students who take advantage of it. But I don’t see this isn’t a total loss. The student still had to learn the content. Should it matter when they learned it? Through my years of tweaking and experimentation with the method, I have come to believe that this testing process not only leads to deeper learning, but also creates a less anxious classroom.

Statement of Innovation in Teaching from Dr. Jeanine Varner:

“Trey is a remarkably good teacher. We taught together large sections of BCOR (45-60 students). He showed a creative spirit and a genuine humility. He never demanded respect from our students; he received it because of his creativity and his humility. A couple of examples may prove helpful. He added to BCOR a design project, with step-by-step instructions on how to think about problems from a design perspective. It was a new way of thinking for most students, and he walked them through the project in a patient, understanding way. He also added to BCOR as part of class discussion and lecture several aspects of art history—paintings of Jesus, for example. He was excellent at helping students to see in those paintings varying views of Jesus.

Often, after a class session, he would chat with me about what he and I could improve in a lecture or in an assignment. He was quite self-reflective and eager to change what he could to improve as a teacher. I quickly came to admire Trey as a teacher who cared deeply about his material and his students. He was a joy to team-teach with.”

— Dr. Jeanine Varner, Professor Emeritus

SELF REFLECTION

3. Self-Reflection and Improvement

BCOR: The Search for Meaning

One example of using reflection and student feedback to improve a course is exemplified in the restructuring of the way I presented the major research assignment in my BCOR courses. The new approach came about as a result of a series of several events that caused me to want to guide my students to provide better work.

The first event was a very tough semester in which I had several students plagiarize multiple sections of their papers. This is the class mentioned above in Dr. Niccum’s letter of support. After dealing with each of these academic integrity violations, I felt that a better-written assignment that asked for much more specifically-defined outcomes could drastically close the window of opportunity for students to plagiarize. It did, and plagiarism numbers in each of my BCOR classes went down substantially after implementing my new assignment delivery strategy.

The second event that impacted my decision came about from my positive experiences with the Cornerstone Annotated Bibliography assignment. The success of the Annotated Bibliography is due, in part, to its stepped structure where the assignment is broken into four sections that build upon one another. After teaching BCOR several times, I realized that, unfortunately, very few of my students were prepared to embark on the task of writing a well-crafted research paper unguided. In my new strategy, I created an assignment worksheet that guided them through the research process, requiring them to collect sources, define their theses, develop their arguments, respond to counter-arguments, and draw conclusions before they began the actual writing. The result led to much stronger papers.

Finally, the third event that caused me to rethink my approach was reading a paper published by IDEA (a non-profit organization that publishes evidence-based research for educators in higher education) on improving critical thinking. “IDEA Paper 37,” written by Cindy L. Lynch and Susan K. Wolcott, focuses specifically on providing steps to help students improve their arguments through critical thinking processes. Lynch and Wolcott prescribe four steps for improving critical thinking: helping students (1) identify problems, (2) explore interpretations, (3) prioritize and communicate arguments, and (4) re-address the problem. This much more systematic approach to presenting the assignment challenges students to not merely find research and report on it, but to process it, develop a personal stance, and identify the strengths and weaknesses of their positions.

Throughout BCOR, our learning objective was to introduce and compare three metanarratives (Christianity, Islam, and secular humanism) and reflect upon them as different visions of human flourishing. We explored each of these metanarratives through case studies on transhumanism, which often exposes the promises, challenges, ethics, and philosophical underpinnings of each of these visions of flourishing. The assignment asked students to choose a group from two of the three metanarratives (for example, Southern Baptists from the United States and Sunni Muslims from Iran, or New Atheists from Oxford, England) and compare common perspectives or philosophical approaches from those groups on a transhumanistic technology (such as human cloning or gene therapy).

As mentioned earlier, one of the benefits of this approach is that the question was so specific students were not able to easily plagiarize the work. In fact, they couldn’t even hire someone else to write the paper for them unless the person had taken the class.

Then, my co-teachers and I implemented a three step assignment based on the theories of Lynch and Wolcott:

Step One: Sources and Research Question (Link)

Prior to proceeding to writing, students were required to begin their paper by selecting the technology and metanarratives they would research. This assignment asked them to submit their research questions and a working bibliography with 8 scholarly sources.

• Step One Example (Link)

Step Two: Worksheet (Link)

For step two, students were required to complete an exhaustive research guide based on the questions presented in IDEA Paper 37 by Lynch and Wolcott. The worksheet begins with introductory questions leading to their research question and introductory paragraph. Then, the worksheet challenges them to explore different interpretations and perspectives on the technology from within the metanarratives they are studying. In this section, students begin to identify arguments both for and against their technology while also identifying potential weaknesses. Next, they must identify any areas of uncertainty or gaps in their knowledge to help them strengthen their positions. Finally, they move to drawing and communicating conclusions.

• Step Two Example (Link

Step Three: Final Draft (Link)

For the final draft, students had to prepare a roughly 2,000 word paper analyzing the transhumanist technology as it is evaluated by scholars from the two metanarratives they chose.

• Step Three Example (Link)

In the example provided, a former student engages in a thoughtful reflection on neoeugenics in light of the positions of Reformed Christian theologians and spiritual theists. The paper perfectly follows the worksheet, analyzing multiple arguments from each metanarrative, identifying their respective strengths and weaknesses, and providing a thoughtful examination on the difference not only in the conclusions, but in the reasoning behind each respective position.

Statement on Self Reflection from Steve Hare

“Dr. Trey Shirley has demonstrated good self-reflection as a teacher and mentor to the Cornerstone faculty. He has identified areas where he might present bias and has acknowledged such in a way that encourages open-mindedness. He has presented ideas for Cornerstone classes in a manner that elicits feedback and response. He has shown insight into teaching strategies as well an openness to suggestions and ideas from fellow faculty. He has grown in his ability to lead other Cornerstone faculty with gentleness and conviction. He is a valuable colleague to many and worthy of a promotion.”

— Steve Hare, Instructor, Department of Bible, Missions, and Ministry

Statement on Self Reflection from Ryan Feerer

“I have not met many faculty members who are as dedicated to their students as Trey Shirley. He is the most reflective in our department—constantly improving his courses and the way he delivers content. It is admirable. His knowledge of design and the arts is very impressive and has played an important role in the development of our 20/20 Innovation Grant. Trey is instrumental in the success of our department. Not only with our graphic design program, but also the fine arts. We and the university at large, need more people like him. I fully support Trey’s promotion.”

— Ryan Feerer, Professor, Department of Art + Design

2. Integration of Faith and Learning

“While not a generally recognized quality of effective teaching, the integration of faith and learning is critical for the faculty member at Abilene Christian University. The faith informed professor seeks to meaningfully integrate faith and learning, assisting students in identifying integral relationships that exist between the discipline and Christian theological perspectives.” – ACU Faculty Handbook

FAITH & LEARNING

Statement on Integration of Faith & Learning

For me, working in Christian higher education is an invitation to partner with God in sharing with college students the good news of God’s truth, justice, and love. This invitation is both frightening and exhilarating. It is frightening because to approach one’s work as a vocation is to reject the compartmentalization of our “spiritual” and “professional” selves and instead seek to empty one’s self in all arenas of life. Approaching my work as a calling is exhilarating because seeking the mission and justice and worship of God is always overwhelming and wonderful and mysterious. To serve as a leader in a Christian university is to engage in a calling that is at once communal, imaginative, and spiritual.

A Communal Calling

An Imaginative Calling

A Spiritual Calling

Evidence from Student Evaluations

-

-

- “He cares about his students and shows Christ through the way that he teaches.” – Core 110.02, Spring 2018

- “He was not afraid to talk about God” – ART 222.01, Spring 2018

- “He was always very considerate of our opinions and circumstances in the context of the class discussion. He had a high standard and encouraged us to work our best, something I appreciate. He also presented us with difficult subjects and world problems in order to push our thinking and open our minds. He always integrated Christian values and principles into answering these questions while encouraging us to think for ourselves.” – CORE 110.01, Fall 2017

- “He always related church topics and problems to what we were learning, and he even made us think about this relates to our faith. He also demonstrated the fruits of the Spirit whenever he taught and answered questions as well. He never seemed negative, but was always positive. I cannot think of a time when I did not see Dr. Shirley displaying a Christ-like character.” -CORE 110.01, Fall 2017

- “Dr. Shirley shared his importance of Christ, and at times he would pray over us.” -CORE 110.01, Fall 2017

- “He was very understanding and found a way to illustrate that no matter what you are doing you need to do it with a christ centered focus.” – CORE 110.01, Fall 2017

- “[He] Invites people to his home and treats them like family.” -CORE 110.02, Spring 2017

- “He related content to scripture frequently.” -CORE 110.02, Spring 2017

-

Statement on Integration of Faith & Learning from Dr. Cliff Barbarick:

“I’ve had the pleasure of co-teaching BCOR 310 with Dr. Shirley several times over the past few years. In this class, we challenge students to explore their own faith as they formulate a definition of the “good life” and compare it with other systems of belief. These conversations usually require us to deconstruct thin and fragile parts of our students’ faiths in order to help them replace it with something more robust and lasting. It’s delicate work, and I’ve always appreciated having Dr. Shirley as my partner in this setting. He brings an academic rigor and intellectual honesty that encourages students to ask the tough questions, but he combines that with a theological thoughtfulness and pastoral sensitivity that encourages their faith formation. This rare combination makes Dr. Shirley a valuable part of our faculty at ACU. “

— Dr. Cliff Barbarick, Associate Professor, Department of Bible, Missions and Ministry

3. Knowledge of the Subject Matter

“The teacher who knows the subject matter has achieved the first condition for good teaching.” – ACU Faculty Handbook

KNOWLEDGE OF SUBJECT

Statement on Knowledge of Subject Matter

Central to the work of a professor is possessing knowledge and expertise in a field of study. I believe that knowledge in artistic disciplines is best formed in practice and that experimentation and exploration are essential for students to truly grow in a discipline. In the classroom, I try to direct students to new and diverse ideas and practices drawn from years of my own research and practice. Through countless hours of reading, practice, research, and preparation, I aspire to create a classroom environment that empowers students with the resources they need to engage in academic inquiries of their own and experiment with their findings. My hope is that in doing so, they will be equipped to make connections between their work and research and their lives. Through discovery and innovation, I hope to model for my students a lifetime pursuit of wisdom and knowledge.

Statement on Research

Evidence from Student Evaluations

-

-

- “Trey is so fun to interact with in class and has such a fun sense of humor that connects with the kids so well! His heart for others and incredible knowledge about art history is actually ridiculous. LIKE HOW DO YOU KEEP ALL THAT STUFF IN YOUR BRAIN TREY, HOW?? Anyways, you rule, you’re cool, stay in school at ACU.” – ART 222, Spring 2021

- “It was clear that Dr. Shirley knew what he was talking about and had a passion for a subject. This made it easy to stay engaged and made the material seem considerably more interesting.” -Student from CORE 110.01, Fall 2019

- “The depth of his knowledge was amazing. He made his lectures interesting by not solely relying on the information that was on the slide presentations. Both essays were great and I wish there was a third essay.” – ART 221.01, Fall 2019

- “He is very knowledgable about the subjects, and he went in depth into the history surrounding all the art pieces.” – Student from ART 440.01, Spring 2017

- “He explained things well and showed his deep knowledge of the subject.” Student from ART 222.01, Spring 2015

-

Statement on Knowledge of Subject Matter from Prof. Dan McGregor

“The knowledge base that Trey brings to our department is formidable. His wide-ranging experiences in graphic design, branding, theology, and even architectural design and house renovation mean that as a studio art teacher, he is able to provide both a theoretical and a hands-on background for his assignments that I could only dream of having.

In the realm of art history, Trey is unmatched in his knowledge in our department. Out of all my A&D colleagues, he’s the primary one I can go to for conversations about illustrators, from Aubrey Beardsley to Ralph McQuarrie. Moreover, Trey is a treasure trove of great anecdotes about famous artists from the past. The art history stories he’s introduced me to (such as the saga of the “Slant Step”) have made their way into my own classes. Conversations with him have definitely deepened my knowledge of art history and given me new fodder for the classroom.“

— Dan McGregor, Professor, Department of Art + Design

Statement on Knowledge of Subject Matter from Karen Cukrowski

“Often, it seems to me, professors fail to synthesize innovative scholarship and the significance of their findings. Not so with Dr. Trey Shirley, whose skills of analysis and research find both their roots and their results in application. Trey’s work in marketing, graphic arts, and design thinking are integrally connected, for example, to the practical and frank implications of these areas in the church he so loves. Even there, he goes beyond mere excellent research and critique, where many good academics stop, but posits and finds theologically, sociologically, and scientifically sound solutions and suggestions that bear consideration in our ever-shrinking and changing houses of worship. Similarly, in his outstanding work with and direction of Cornerstone, which touches 100% of our student body at ACU, Trey guides us, the teachers, through an organized and challenging course, raising the rigor to which our students are exposed, all the while focusing us on application, the So What? of each activity and discussion.”

— Karen Cukrowski, Cornerstone Instructor

4. Ability to Communicate

“The teacher who knows the subject matter has achieved the first condition for good teaching.” – ACU Faculty Handbook

ABILITY TO COMMUNICATE

Statement on Ability to Communicate

Central to learning is the teacher’s ability to communicate effectively with their students; without effective communication, teaching is, at best, ineffective and, at worst, harmful to student learning. But, transformational learning does not occur through communication alone; rather, learning is cultivated through a partnership between the teacher and student engaging in a dialogical process of intentional reflection that culminates in the student becoming an active agent in their own learning. Through intentional course design that is attentive to the situational factors of the classroom and the learning objectives of the course, while also responsive to the feedback of students, a teacher may create an environment that makes space for more than the reception of information, but the synthesis and exploration of new ideas.

Evidence from Student Evaluations

- “Dr. Shirley is highly educated and experienced in his field of study. He has thoroughly explained concepts and fundamentals of art through his own Powerpoint lectures, as well as his personal critiques/comments on my artwork. I have gained so much knowledge about art and design; I have seen my creativity really reach new levels through each assignment starting at the beginning of the semester till the end. Dr. Shirley has been part of this growth and I am grateful to have had him as my art professor.” – Student from ART 105, Spring 2018

-

Comment from a student taking Cornerstone for the Second time: “Dr. Shirley was pretty awesome, actually. We disagreed occasionally, but in an academic, professional way. Interestingly enough, I didn’t hate being in this class. Especially considering that I failed it the first time because I thought Cornerstone is absolutely useless and that I “learned” less than 5% of the “curriculum” (mainly because I already knew the majority of it, even before I took the course the first time), Dr. Shirley actually managed to make it interesting a solid majority of the time. I came in angry, with extremely low expectations, but I didn’t mind learning from him. I begrudgingly admit that I quite enjoyed the course, although I still think it’s pointless. He’s an excellent educator. Give him tenure, he made a chronic pessimist enjoy something mind-numbingly boring.” – Student from CORE 110.99, Spring 2017

-

“This course was effective because the lectures were put together very well. Dr.Shirley is one of the best professors I have had, he has very good lectures and the lectures are easy to follow along. He also provides more than enough resources for the exams which is very helpful. I also like that he provides different options for projects like writing a research paper or completing a research paper to meet everyone’s needs.” – Student from ART 222.01, Spring 2020

-

“Dr. Shirley is an amazing professor. His use of classroom discussions helps the whole class grow together in thought. The thought provoking questions he gives and the emphasis he puts on thinking and learning is outstanding.” – Student from ART 221.01, Fall 2019

-

“You can tell that Trey LOVES what he does and that he really does know what he is teaching. I personally am not a Graphic Design major, but due to the way Trey taught this class I was genuinely interested. I really liked the format of the class and how the Powerpoints were a mix of lecture and video. I also feel like I really enjoyed not have a ton of test, not for the main reasons but because I really felt like not having a test took away the pressure, so I could just enjoy learning about the subject.” – Student from ART 440.01, Spring 2021

-

“He provided detailed study guides and helpful videos for our benefit. In class, he also showed videos that helped to increase our knowledge of the topics covered. He was always ready for class and very prompt. It was obvious he cared a lot about the subject matter and was very knowledgeable. He showed a strong command of the material.” – ART 222, Spring 2020

Statement on Ability to Communicate from Amy McLaughlin-Sheasby

“When I co-taught BCOR with Trey Shirley, I had the opportunity to witness his pedagogic methods up close. Trey is gifted in utilizing a wide variety of mediums and disciplines in order to articulate, demonstrate, or clarify course content. By incorporating literature, visual art, videos, and music into our class, Trey successfully captured the attention of students who might have otherwise remained disengaged. Trey is also gifted in facilitating class discussion; he knows what types of questions to ask in order to inductively guide students to deeper critical thinking. Co-teaching with Trey inspired me to be more intentional in the way I connect with students in the classroom. “

— Dr. Amy McLaughlin-Sheasby, Assistant Professor, Department of Bible, Missions, and Ministry

Statement on Ability to Communicate from Dr. Paul Morris

“In my years at Abilene Christian University I have team-taught with at least sixteen different professors and all but one of those has been an amazing experience. I always learn a lot and I think it is a wonderful model for students to see faculty persons continuing to learn. One of those great experiences was teaching with Trey Shirley.

Trey and I team-taught a section of BCOR in Spring 2015; Trey took the lead in developing our course and did a fantastic job of coordinating the curriculum so that both of our expertise were used in a harmonious and natural way with little or no thematic discontinuity. He demonstrated concern for the students and proper rigor for a junior/senior level course. His lectures were clear and demonstrated his wide-ranging interests including art, design, and theology. I believe this multidisciplinary/ interdisciplinary teaching is one of the important innovations that we need to encourage. He was able to generate student involvement through discussion of topics in the ‘search for meaning.’ Trey is an excellent teacher.

Trey and I have had several private conversations, primarily concerning liberal arts education. I know that he, as do I, strongly believes in the importance of the liberal arts in helping the students become whole persons. I think we need more faculty who are invested in that form of education.”

— Dr. Paul Morris, Professor Emeritus

5. Interest in the Student

“The effective teacher takes an interest in students as individuals. The teacher is conscious that teaching also offers opportunities to help the student experience ethical and spiritual growth, understand the implications of the discipline in matters of faith, and develop a Christian philosophy of life.” – ACU Faculty Handbook

INTEREST IN STUDENT

Statement on Interest in Student

Teaching is nothing without students. At the heart of what we do every time we walk into the classroom is an amazing group of smart, talented, and eager learners who deserve our fullest interest. I believe that students learn best when they know that the person teaching them cares for them personally. Letting our students know that we care for them keeps them engaged in the learning process and provides energy and reason to learn new things.

Interest in the student is a fundamental instructional approach to teaching that transcends educational trends and new technologies, reaching beyond the minds of learners and into their hearts, helping them see meaning for themselves. Although meaning comes in various forms and is expressed in many ways, when students have opportunities to understand their value, learn more about themselves, and connect with a bigger picture, a bigger Story, they are able to draw from a source of motivation that goes deeper than grades.

Evidence from Student Evaluations

-

-

- “The way Dr.Shirley interacts with his students before the lectures are great because he gets to know us a little better and is able to work with us.” – Student from CORE 110, Fall 2020

- “He was very involved and tried to get us involved. Being an intro class, he truly cared for us and was always ready to help us. In the beginning of the year and throughout the year he was very open and helpful with everything. It was effective because he stuck to the syllabus and everything was structured.” Student from CORE 110, Fall 2019

- “Wonderful lectures that I wish would have continued over Zoom every week during the online period. Great knowledge of and enthusiasm for the class material. Genuinely cares about the students and their success. Love that the class is a balance of exams, essays, and presentations.” – Student from ART 222, Spring 2020

- “He was very prepared for class, and you can tell he genuinely cares for us as students.” Student from CORE 110, Fall 2018″

- Dr. Shirley is a great professor and he really showed that he cares for each of his students.” – Student from CORE 110, Fall 2020

-

Collected Statements from Former Students

- “During my time at Abilene Christian University, I have had Dr. Trey Shirley as my professor for three courses and can honestly say he is one of the best professors I’ve had in my college career. Trey’s passion for his courses is infectious and promotes an active learning environment where students can feel comfortable and confident. Trey’s interest in his student’s transcends the classroom, not only does he seek out opportunities to further his students’ knowledge in the real world, but his character with his students is one that is approachable, relatable, and honestly enjoyable. Professor Shirley’s heart for his students is unmatched” – Daniel Tapia, ’19

- “I have been lucky enough to have Dr. Shirley for four art history and CORE classes over my three years at ACU, including my Cornerstone class my freshman year. From the beginning, two things have been clearly evident about Dr. Shirley – he is very passionate about the subjects he teaches, and he takes a very sincere interest in his students’ lives and education. He teaches with enthusiasm in a way that guides students to really invest in the subject and push themselves to learn. Dr. Shirley truly epitomizes one of the primary reasons I chose to attend ACU: a personable and passionate professor that genuinely cares for his students and their education. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to learn from him.” – Denver Gravitt, ’19

Statement on Interest in Student from Dr. Rodney Ashlock

“It is my pleasure to write to you about Dr. Trey Shirley’s interest in students. I witnessed first-hand Trey’s concern and care for our students when I co-taught a section of CORE 210 with him in the spring of 2015. We had a class of around fifty students. I remember vividly how patient he was with the students who were experiencing a difficulty or just undergoing stress. He knew the stories of several students and would often shape assignments that would connect with them in a special way. He wanted them to learn, but it was important for them to be shaped into better citizens and young Christians. In my opinion, he treated all the students justly.

I have always found Trey congenial and ready to help whenever necessary and I consider it an honor and a delight to write this letter for him. In my mind, he represents the best of what this university has to offer.”

— Dr. Rodney Ashlock, Chair, Department of Bible, Missions, and Ministry

Unsolicited Notes from Students

6. Reflection on Student Evaluations

Although the Faculty Handbook does not call specifically call for a reflection on Student Evaluations (it only calls for them to be included in the portfolio), the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Dr. Greg Straughn, encouraged me in my pre-tenure review to include a longitudinal evaluation of my student evaluations. Below, I report my findings.

REFLECTION ON STUDENT EVALUATIONs

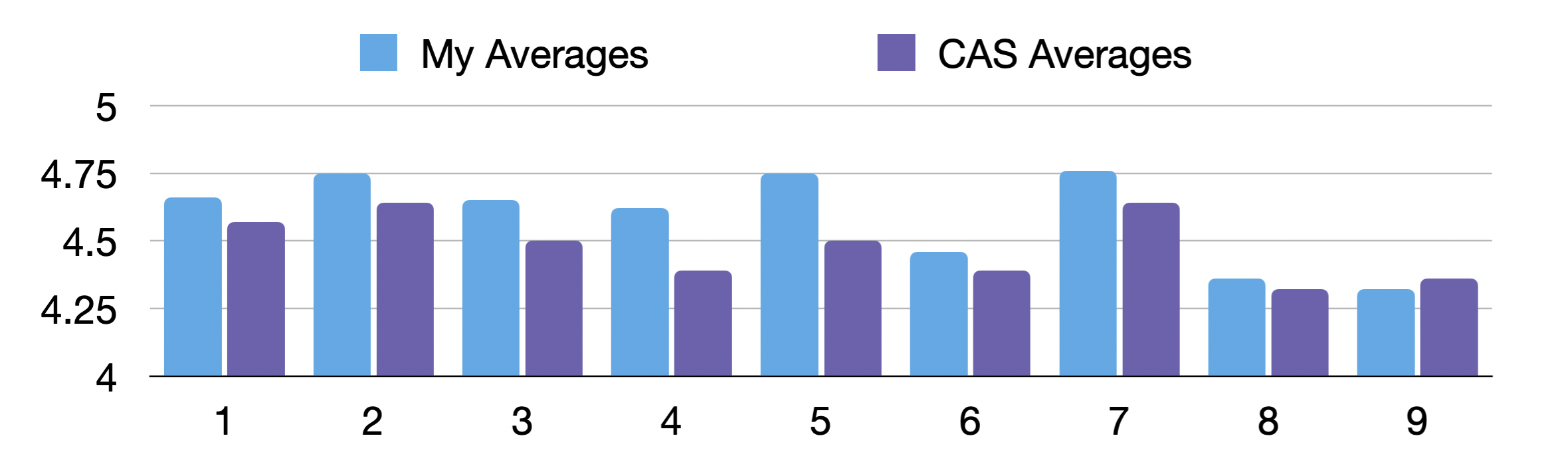

Longitudinal Assessment

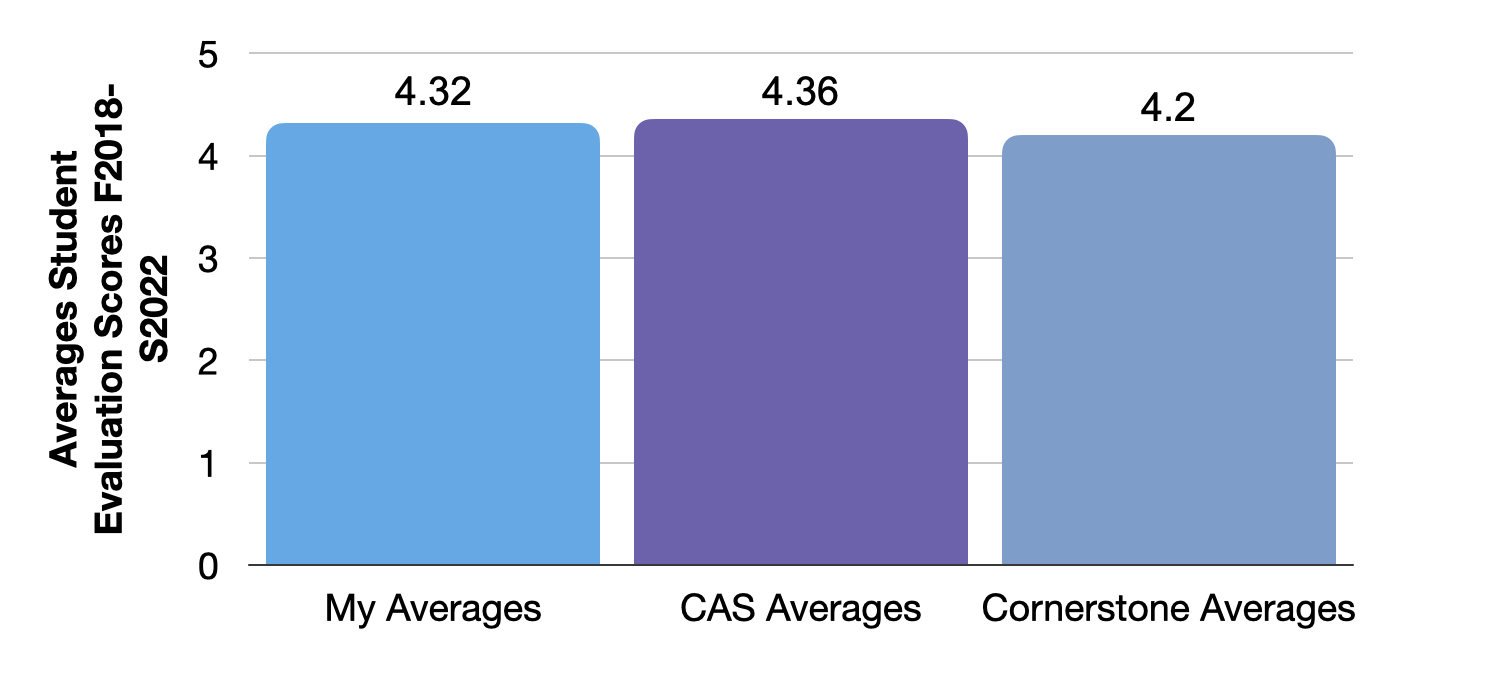

In order to evaluate my performance on student evaluations, I began by inputting the cumulative averages of my performance on each of the questions assessed in the objective section of student evaluations into a spreadsheet. I then compared them with the cumulative averages of the College of Arts and Sciences. Out of the nine categories of quantitative data collected since the implementation of the BlueEra Course Evaluation system, placed in service in Fall of 2018, my average student evaluation scores exceed my college’s (the College of Arts and Sciences) in eight categories (See chart below).

Student Evaluation Questions

- The instructor was receptive and responsive to my questions and concerns.

(My Averages = 4.66; CAS Averages = 4.57; Diff. = +.09) - The instructor treated me with respect and fairness.

(My Averages = 4.75; CAS Averages = 4.64; Diff. = +.11) - The instructor created a hospitable environment for learning.

(My Averages = 4.65; CAS Averages = 4.5; Diff. = +.15) - The instructor graded assignments and/or exams in a timely manner.

(My Averages = 4.62; CAS Averages = 4.39; Diff. = +.23) - The instructor was well prepared for class.

(My Averages = 4.75; CAS Averages = 4.5; Diff. = +.25) - The instructor communicated the course material clearly.

(My Averages = 4.46; CAS Averages = 4.39; Diff. = +.07) - The instructor showed a genuine interest in the subject and a desire to share it with the students.

(My Averages = 4.76; CAS Averages = 4.64; Diff. = +.12) - My experience in this course reflected ACU’s mission to educate students for Christian service and leadership throughout the world.

(My Averages = 4.36; CAS Averages = 4.32; Diff. = +.04) - As a result of this course experience, I have a better understanding of the subject matter.

(My Averages = 4.32; CAS Averages = 4.36; Diff. = -.04)

Raw Data

| Question | My Averages | CAS Averages |

| 1 | 4.66 | 4.57 |

| 2 | 4.75 | 4.64 |

| 3 | 4.65 | 4.5 |

| 4 | 4.62 | 4.39 |

| 5 | 4.75 | 4.5 |

| 6 | 4.46 | 4.39 |

| 7 | 4.76 | 4.64 |

| 8 | 4.36 | 4.32 |

| 9 | 4.32 | 4.36 |

Regarding the question where I did score lower, my average scores are still higher than the Cornerstone averages. Considering that 50% of the classes I taught during this period were sections of Cornerstone, and Cornerstone is not included in the CAS averages, my averages are higher than the combined averages of the CAS and Cornerstone (CAS and Cornerstone Avg. = 4.28; my Avg. =4.32; Diff = +.04) This is significant because Cornerstone has long been known as a challenging course in regard to this specific question (“As a result of this course experience, I have a better understanding of the subject matter.”). As one of the learning objectives of Cornerstone is to introduce students to methods of research and critical thinking across multiple disciplines, it is understandable that students would get confused or overwhelmed with the diverse subject matter.

Raw Data

As a result of this course experience, I have a better understanding of the subject matter.

(My Averages = 4.32; CAS Averages = 4.36; Diff. = -.04;

(My Averages = 4.32; Cornerstone Averages = 4.2; Diff. = +.12)

Changes in Response to Critical Student Evaluations

As shown above, in evaluating my teaching effectiveness, I have employed a number of different strategies throughout the years. Through team teaching, I regularly employed the assistance of my peers to help me identify areas in which I need to improve as an instructor. Through opportunities such as annual reviews, regular evaluation of course learning outcomes, and personal reflection, I have engaged in self-evaluation to help elevate my classroom instruction and create more targeted strategies for teaching. And, I have sought the input of my students through both formal and informal measures to help me improve as a teacher.

While student evaluations can provide some useful feedback for professors, there are also issues with using them to evaluate performance, especially if they are the only method of feedback a person is engaging for reflection. For example, one of the challenges of using student evaluations is that they can often indicate a student’s personal preferences for a teaching style, personality, or sense of humor, rather than evaluate the effectiveness of the an instructor’s teaching. Likewise, student evaluations can give an incomplete picture of the professor’s ability as a teacher, both through the ways and type of feedback collected.

Nevertheless, each semester I am eager to comb through the feedback provided by my students (especially the qualitative sections) so that I may learn how to improve my course instruction. Over the years, this information paired with feedback I collected on my own from students through personal conversations and periodic Canvas surveys have been invaluable for helping me improve as an instructor. Below, I highlight three specific changes that I have made as a result of feedback collected through these different means:

Memorization

As an art history professor, one of the most consistent critiques I have received of my assessments throughout the years has been my requirement for students to memorize information. Typically, this includes memorizing artist’s names, periods or eras in which a work was created, approximate dates, and artwork locations. Examples of student comments include:

- “Make the tests easier because not everyone can memorize as well as others” (ART 222, Spring 2015)

- “Great content but wish there had been more tips on how to learn the dates and facts and retain them.” (ART 221, Fall 2015)

- “All the material was very interesting and enlightening, but I feel there wasn’t adequate prep or aid in memorization of the content.” (ART 221, Fall 2016)

- “If there are going to be that many dates to memorize, it would be nice to have an explanation as to why the dates are important and why we need to learn them all.” (ART 222, Spring 2017)

In hearing these complaints, it has been helpful to me, not in that I have necessarily removed memorization as part of my course requirement, but because it has helped me realize (1) that many students believe that memorization is not a valuable way of learning and (2) many students have never been taught how to memorize information.

Memorization plays a crucial role in creating a strong foundation of knowledge in any new discipline. Learning involves building upon previously acquired knowledge, and memorizing key concepts and vocabulary provides a foundation upon which this learning can take place. Without memorization, it is difficult to grasp more complex concepts and ideas, and to make meaningful connections between different pieces of information. When learning a new subject area, memorization is invaluable. After all, one cannot learn a new language without also memorizing the vocabulary. In my classes, I now reiterate this at multiple points throughout the semester because I want my students to better understand that memorization IS a critical component of building a strong foundation of knowledge in a new field.

In addition, I also now give a brief lecture on how to memorize information. I focus on teaching many of the points made in the book Make it Stick. This includes encouraging them to avoid massed practice and cramming, and instead engage in retrieval practice through quizzing and summarizing. I teach them how to create mnemonic anchors to help memorize dates (for example, in 1492, Columbus discovered the Americas. Was this artwork made before or after this discovery?). And, I encourage them to space out their studies, starting with their notecards or Quizlets two or three weeks before the exam, instead of two or three days prior.

Ultimately, I stand by my assertion that memorization IS learning. Yes, we want to get to the deeper levels of learning in Bloom’s Taxonomy, but we can only do so if we have a firm foundation of knowledge from which to build.

Building Better Courses

Another area for improvement that has been pointed out to me by my students is that I do not remind them frequently enough of due dates or assignments or talk about them in class enough. Often, when students come to class we are quickly jumping into material and engaging in discussions about artworks or reading assignments for the day. By the time class ends, it has not been my habit to pause and remind them of what is coming up or when assignments are due. Examples of these comments include:

- “Point us to canvas more or be more clear about assignments and due dates.” (Art 105, Fall 2019)

- “Give us more information about bigger projects/assignments in class” (ART 222, Spring 2021)

- “I saw the connections, but the homework assignments were not mentioned during class or explained why they were relevant.” (ART 222, Spring 2022)

To remedy this, I have recently instituted several changes to make the experience better for my students. First, I have made an intentional effort to pause at the beginning of every class after taking attendance to look backward, look at what we’re doing today, and to look forward. This simple strategy has been really helpful, not only for helping students have greater awareness of assignment expectations and due dates, but has also created more opportunities to make connections from class-to-class. Opening up for a time to take questions has also helped uncover a number of concerns students have regarding how to do a certain assignment or what exactly they are being asked to do.

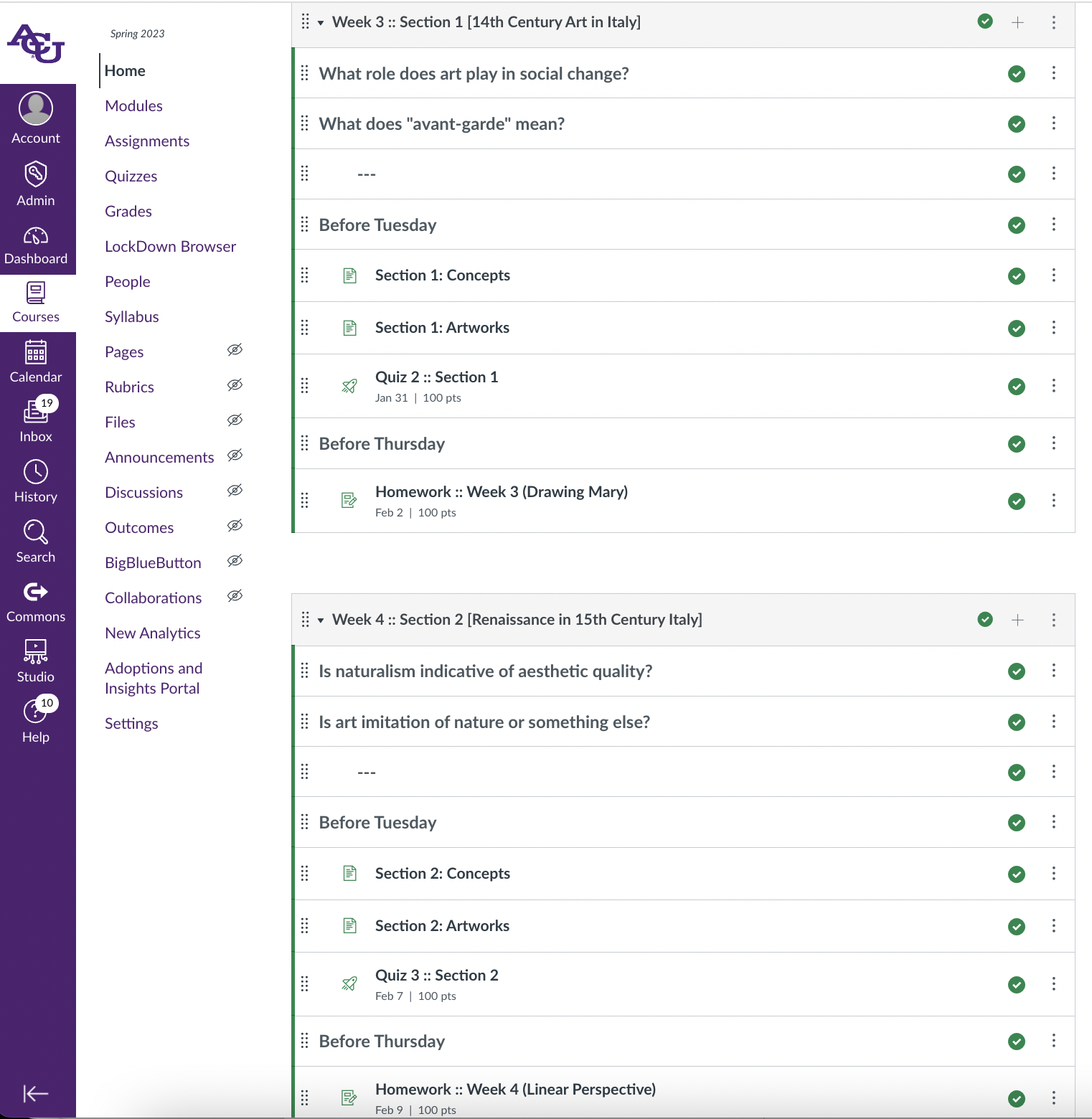

A second alteration I have made has been to design a better Canvas course. As a graphic designer, I am always looking for ways in which design can help solve problems. So, to me, it makes a lot of sense to use design and automation to make a better experience for my students. Through years of iteration, I have now landed on using the Modules section of Canvas to clearly map out a student’s experience. These Modules are designed prior to the start of the semester, so when a student logs in on the first day of class, they can see exactly what exercise we will be working on in week twelve. All assignment due dates and times are plugged in and each week of the semester is contained within a module. Inside the modules, the framing question(s) for the week’s discussion is posted at the top, followed by headers for each day of the week. Under these days of the week I have placed all assignments, quizzes, and readings to clearly demarcate their due dates (See image below). At the end of the lecture, I add my course slides to the module for reference.

By employing these simple, but effective strategies, I believe I have made a better overall experience for my students.

Weekly Art Assignments

One final example of how I have responded to student comments is that I have noticed that in teaching art history, many of my students (especially art majors) want to do more hands on learning. This led to the creation of our weekly art assignments.

- “May need to add more daily grades to help students learn better rather then just simply lecturing.” (ART 222, Spring 2017)

- “Provide more assignments so that grades don’t rely purely on very long and difficult exams.” (ART 221, Fall 2019)

- “Tests aren’t valid assessments of what we learn in class.” (ART 221, Fall 2017)

Each week throughout the semester, students do a homework assignment that falls into one of three categories: (1) a written response to a theme, (2) an objective artistic assessment, or (3) a creative artistic product.

The written responses are exactly what they sound like. Students are asked to find examples of kitsch from their lives, write a legal definition for art in response to a legal case, or explain the differences between plagiarism, forgery, and sampling or quoting in art. These short essays are constructed to invite students to engage more deeply with content from the week’s lectures and to make connections with their own lives.

Objective artistic assessments are activities where students prove that they understand a specific artistic concept. This might involve them drawing a building using one point perspective, taking a chiaroscuro photograph, or following the “rules” for drawing a human figure on a grid following Egyptian hieroglyph standards for composite images. In essence, these are tasks where a student may objectively show comprehension of the concept.

Finally, my favorite homework assignments are creative artistic products. Examples of this might include having a student turn a work of art into a pop-up book, re-illustrate it for a children’s picture book, or create a mood board for their own French salon. One example involves having them draw Mary, the mother of Jesus. In the drawing they have to choose what moment to depict Mary, what style speaks most to her character and reflects the scene they are illustrating, what color to make Mary’s clothes, and more. All follow in the footsteps of a long tradition with many different examples that deal with this question. The images the students come up with are not only creative, they are often powerful and full of rich meaning.

Welcome

Summary

Curriculum Vitae

Support Materials

I. Teaching

Reflection on Teaching Effectiveness

University Requirements

Departmental Requirements

II. Scholarship

Reflection on Scholarship

Scholarship Inventory

Scholarship Highlights

III. Service

University Requirements

Departmental Requirements

IV. Collegiality

Reflection on Collegiality

Significant Partnerships and Collaborations