Recapitu – what?

While preparing for the quiz last week, I was struck by one of the terms that we were asked to define: recapitulation, so I decided to do some more research on this term. I have gathered that there were several forms of this recapitulation theory (which was influential, but is no longer accepted).

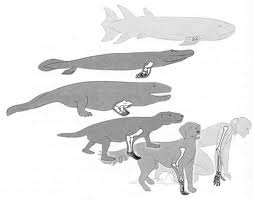

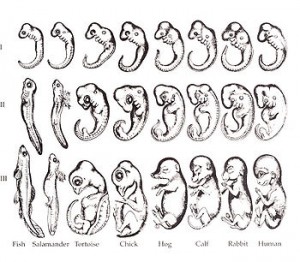

One of the earliest recapitulation theorists was Ernst Haeckel who believed that a developing embryo followed the evolutionary phases of each species that was in its evolutionary line. He made drawings of human embryos in each phase, sometimes overemphasizing the features that he wanted to highlight, but these drawings were used in biology text books. Haeckel showed how human embryos start out with gill like openings that eventually develop into the jaw and throat area. He said that this was because humans had a fish-like ancestor. Modern scientist have rejected this theory in part because even though some stages of embryonic development may seem to look like another species, at no time are these apparent similarities functional. That is the openings that look like gills could never function as gills.

Other theorists who embraced the recapitulation theory applied it to areas such as social development, child development, and education. Herbert Spencer believed that children learned knowledge in the same order that human species mastered the knowledge originally. G.S. Hall believed that there was a one-to-one correlation between child development and evolutionary stages.

There is an interesting article discounting the recapitulation theory on the Institute for Creation Research which you can peruse at your leisure here: http://www.icr.org/article/heritage-recapitulation-theory/. It links Freud to the recapitulation theory, basically stating that Freud believed that all psychosis was functional for our species sometime during evolution, but is no longer useful. Consider the following:

In a 1915 paper, Freud demonstrates his preoccupation with evolution. Immersed in the theories of Darwin, and of Lamarck, who believed acquired traits could be inherited, Freud concluded that mental disorders were the vestiges of behavior that had been appropriate in earlier stages of evolution.”

The evolutionary idea that Freud relied on most heavily in the manuscript is the maxim that ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny,’ that is, that the development of the individual recapitulates the evolution of the entire species.

I feel like the recapitulation theory is another example of confirmation bias. It is a theory that seems palatable to many atheists, that life is just a series of explainable patterns. Of course confirmation bias also occurs with Christians. People latch on to anything that will help support what they already believe. Sometimes, even proof to atheists that God doesn’t exist is proof to Christians that he does. I remember when we were talking in class about the brain’s response to God and religion. We said that people often say that because there was an area of the brain that is active when we are engaged in religious or spiritual activities, that it proves that it the feelings are physiological instead of any spiritual connection. As a Christian, I think, that those brain connections are proof that there is a God. Why wouldn’t God make our brains receptive to him?