The world of comic books is escapism and entertainment. The good guys always win and the bad guys always lose. They are filled with colorful images and expressions. We can see ourselves in the pages even. There’s now an entire market for the comic book universe with movies, movie studios, games, TV shows, video games, they are not going anywhere anytime soon.

But are comic books as wholesome and fun as some would like?

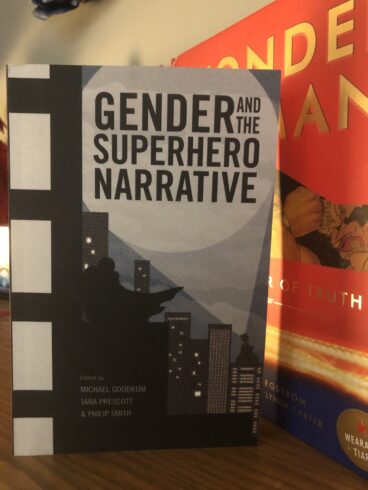

The explosive popularity of San Diego’s Comic-Con, Star Wars: The Force Awakens and Rogue One, and Netflix’s Jessica Jones and Luke Cage all signal the tidal change in superhero narratives and mainstreaming of what were once considered niche interests.

The explosive popularity of San Diego’s Comic-Con, Star Wars: The Force Awakens and Rogue One, and Netflix’s Jessica Jones and Luke Cage all signal the tidal change in superhero narratives and mainstreaming of what were once considered niche interests.

Yet, just as these areas have become more openly inclusive to an audience beyond heterosexual white men, there has also been an intense backlash, most famously in 2015’s Gamergate controversy, when the tension between feminist bloggers, misogynistic gamers, and internet journalisms came to a head. The place for gender in superhero narratives now represents a sort of battleground, with important changes in the industry at stake.

Gender and the Superhero Narrative launches ten essays that explore the point where social justice meets the Justice League. Ranging from comics such as Ms. Marvel, Batwoman: Elegy, and Bitch Planet to video games, Netflix, and cosplay, this volume builds a platform for important voices in comics research, engaging with controversy and community to provide deeper insight and thus inspire change.

EC Comics examines a selection of their works—sensationally-title comics such as “Hate!,” “The Guilty!,” and “Judgement Day!”—and explores how they grappled with the civil rights struggle, antisemitism, and other forms of prejudice in America. Putting these socially aware stories into conversation with EC’s better-known horror stories, Qiana Whitted discovers surprising similarities between their narrative, aesthetic, and marketing strategies. She also recounts the controversy that these stories inspired and the central role they played in congressional hearings about offensive content in comics. The first serious critical study of EC’s social issues comics, this book will give readers a greater appreciation of their legacy.

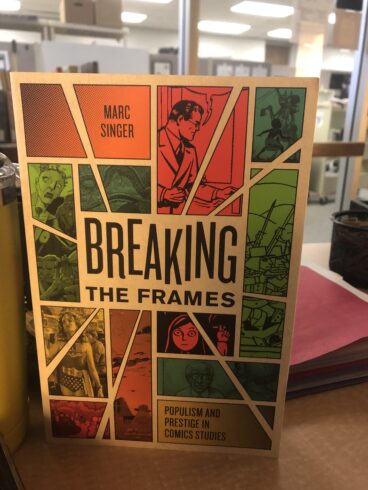

Comic studies has reached a crossroads. Graphic novels have never received more attention and legitimation from scholars, but new canons and new critical discourses have created tensions within a field build on the populist rhetoric of cultural studies. As a result, comics studies have begun to cleave into distinct camps—based primarily in cultural or literary studies—that attempt to dictate the boundaries of the discipline or else resist disciplinary itself. The consequence is a growing disconnect in the ways that comics scholars talk to each other—or, more frequently, do not talk to each other or even acknowledge each other’s work.

Breaking the Frames: Populism and Prestige in Comics Studies surveys the current state of comics scholarship, interrogating its dominant schools, questioning their mutual estrangement, and challenging their propensity to champion the comics they study. Marc Singer advocates for greater disciplinary diversity and methodological rigor in comics studies, making the case for a field that can embrace more critical and oppositional perspectives. Working through extended readings of some of the most acclaimed comics creators, Singer demonstrates how comics studies can break out of the celebratory frameworks and restrictive canons that currently define the field to produce new scholarship that expands our understanding of comics and their critics.

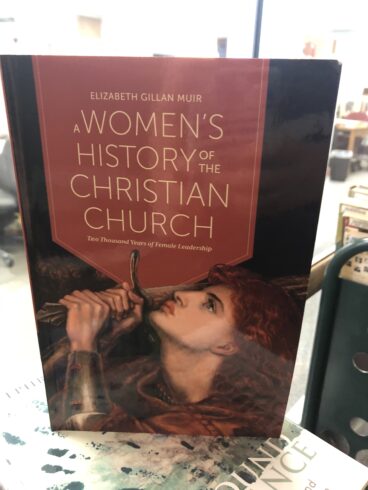

Well, now I have another book to add to my TBR pile (I cannot help myself, can I); Elizabeth Gillan Muir’s A Women’s History of the Christian Church: Two Thousand Years of Female Leadership. As she states in her Preface, this book grew out of an International Women’s Day event, as a panelist of female theological students were asked to discuss the women they admired in the history of the Christian Church. It soon became apparent that most of the audience was unaware of the rich history and contributions of females in the church over the past couple of thousand years. When Muir decided to write this book a friend told her “well, that will be a thin book” (xi). Yet, not only was there much to write about, but Muir was also not fully aware of the remarkable research that has been accomplished recently in this area.

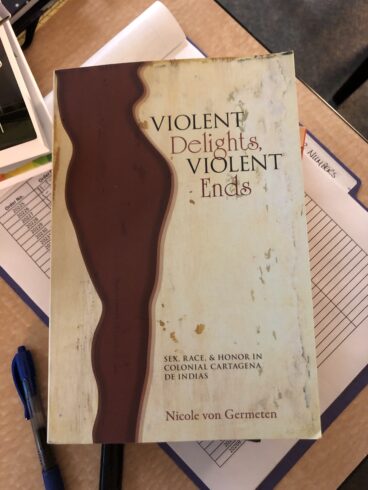

Well, now I have another book to add to my TBR pile (I cannot help myself, can I); Elizabeth Gillan Muir’s A Women’s History of the Christian Church: Two Thousand Years of Female Leadership. As she states in her Preface, this book grew out of an International Women’s Day event, as a panelist of female theological students were asked to discuss the women they admired in the history of the Christian Church. It soon became apparent that most of the audience was unaware of the rich history and contributions of females in the church over the past couple of thousand years. When Muir decided to write this book a friend told her “well, that will be a thin book” (xi). Yet, not only was there much to write about, but Muir was also not fully aware of the remarkable research that has been accomplished recently in this area. Nicole von Germeten takes the reader beneath the surface of daily in a colonial city. Cartegena was an important Spanish port and the site of an Inquisition high court, a salve market, a leper colony, a military base, and a prison colony—colonial institutions that imposed order by enforcing Catholicism, cultural and religious boundaries, and prevailing race and gender hierarchies. The city was also simmering with illegal activity, from contraband trade to prostitution to heretical religious practices.

Nicole von Germeten takes the reader beneath the surface of daily in a colonial city. Cartegena was an important Spanish port and the site of an Inquisition high court, a salve market, a leper colony, a military base, and a prison colony—colonial institutions that imposed order by enforcing Catholicism, cultural and religious boundaries, and prevailing race and gender hierarchies. The city was also simmering with illegal activity, from contraband trade to prostitution to heretical religious practices.