by Madison Roberts | Summer 2023 |

Wherever we go, we take a little piece of that place with us, whether it’s to your neighbor’s house down the street or halfway across the globe where you don’t speak the same language as everyone else. We’re like mosaics, built up of every little encounter we’ve ever had. Every simple act of kindness and every crushing act of cruelty leaves its imprint on our hearts. This became more evident to me on this trip than ever before.

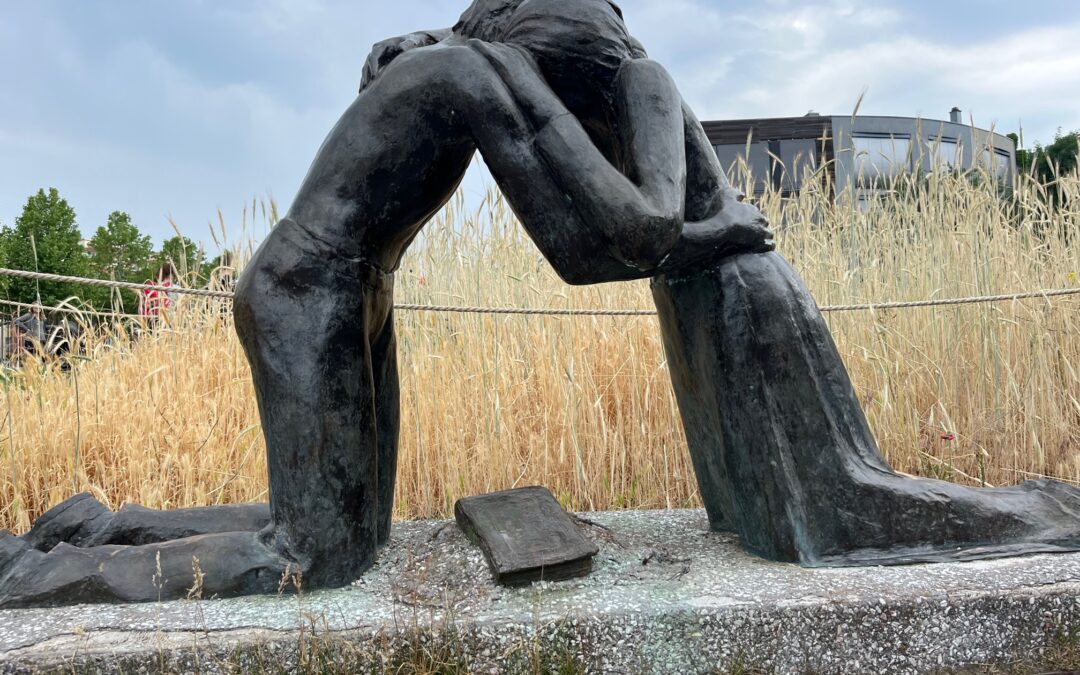

Germany’s history, while it is full of pain and suffering, is mended together by hope and perseverance. Nothing describes this as succinctly as Kathe Kollwitz’s sculpture titled Mother with her Dead Son, which she dedicated to her son who died in World War I. An enlarged version of this sculpture sits in the middle of the bustling city of Berlin. Despite all the chaos around it, once you walk into the building, there is a stillness and a sacredness in the air. I sat and stared at this image of a mother and child for several minutes, though I could’ve been there for hours. The despair on the mother’s face brought me to tears. Together, we mourned the loss of her son. Then, as if Kollwitz was telling me a story, a new kind of mourning began. We were mourning all of the sons, all of the daughters, all of the people who were lost; we were mourning the existence of evil in the world. For me, while this sculpture is representative of one mother’s despair, it is also about humanity’s brokenness, for one life lost to evil is one too many.

The moment that impacted me the most from my time in Germany took place right in Leipzig. Dr. Shewmaker was giving us a tour of the city. We made it to the Church of St. Nicholas, and he began to tell us about its significance in regard to the fall of the Berlin Wall. In 1982, people started gathering at this church for nights of prayer. At first, the gatherings consisted of only a handful of people, but they remained faithful and continued praying. On October 9th, 1989, 70,000 citizens gathered for a peaceful demonstration, carrying signs that read “We are the people.” This demonstration was huge for the peaceful revolution; it acted as a catalyst for more peaceful demonstrations in the surrounding cities. As Dr. Shewmaker was telling this story, an elderly lady walked up behind him. Though she was looking at the nearby memorial, you could tell she was listening intently to what he was saying. When he was finished, the lady introduced herself to us, revealing that she was there the night of the demonstration. She only spoke a little English, but I was hanging on to every word she said. “You don’t understand how important freedom is until you lose it.” To hear someone who had lived in the GDR say that was truly eye-opening. I am so grateful she stopped to tell us her story that day.

Kathe Kollwitz, the lady I met at St. Nicholas Church, and the man who gave me bread to feed birds in the park are all mosaics intricately formed by years of love and loss. Each one of them shared a piece of themselves with me, and I with them. This realization that we are all so interconnected fills me with a sense of gratitude for all the people who have made me who I am, but it also fills me with a sense of responsibility to love my neighbor to the best of my ability.