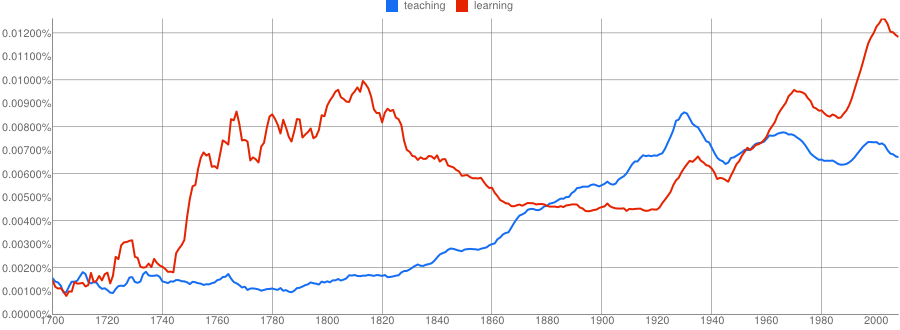

We live in an unprecedented age of literacy, technology, and learning. Google Books’ Ngram viewer allows you to search a digitized library of over 500 billion words from 5 million digitized books reaching back to the 16th century. A quick search on the prevelance of the terms “teaching” and “learning” in publications between 1700 and 2010 yields the following graph.

The general trends observable suggest that over the last three hundred years teaching and learning have become increasingly more important. If you look at the results over the last hundred years there is a clear “peaks” and “valleys” or roller-coaster effect evident in both teaching and learning amidst a general upward trend for learning and relatively flat trend for teaching. Some broad reasons for these trends in the last hundred years might include the following:

- The technological innovations of the 20th and 21st centuries enables “learning” for the masses and so increases the escalation of cultural learning norms. Consider what we considered “educated” in the early 20th century versus what we consider “educated” today.

- Because the peaks and valleys occur at roughly the same intervals an increase in “teaching” leads to an increase in “learning”.

The obvious question posed by these two observations is,

“If teaching and learning behave similarly, why does the relative importance of learning continue to increase over the last hundred years when teaching stays relatively flat?”

I’m not sure there is a single answer that adequately responds to this question, but the question itself illustrates precisely the basis for my personal philosophy of teaching and learning. In this section, I outline my personal philosophy of teaching and learning (informed by these observations), reflect on my first five years of teaching and learning at Abilene Christian University, and outline a variety of evidence that supports my general teaching effectiveness.