Article summary: the differences between, and uses for, power of attorney, medical power of attorney, and living will documents.

These three papers are part of what we call your essential documents (the other being your Will). These documents specifically allow other people to make certain medical or financial decisions for you, in the event you are incapacitated or otherwise unable to decide for yourself. The catch, of course, is that the power these documents provide has to be granted in advance of the incapacitating event.

Put another way, you should probably have these documents drawn up before you are diagnosed with a mental or terminal illness, or have a catastrophic incident.

You can, of course, put restrictions on the holder of your power of attorney. Most powers of attorney documents are what’s called “durable”, meaning they take effect immediately upon giving the paper to your designated holder. There is an element of loss of control here, which must be acknowledged. By granting the power of attorney, you are, in fact, giving this person the ability to act in your stead. This means bank accounts, investment accounts, real estate, vehicles, mineral interests, and monthly bills can be under the control of someone other than you. If you’ve granted this trust wisely, you should have no problems. Then, should some event happen to you that would require your power of attorney holder to need to step into your shoes, you’ll be glad you created this power.

To retain a little more control, you have a few options. You could forgo telling the designated holder about the power of attorney document, until it’s necessary. You could tell the designated holder about the document but not actually give the document into his or her possession. You could use a “springing” power of attorney (which means the power doesn’t become available to the designated holder until certain medical conditions are fulfilled). The downside to a springing power is that medical proof of your incapacity is needed. This might require one doctor’s opinion, or more than one. Depending on circumstances surrounding your incapacity, the need to provide medical proof to begin (or “spring”) the power of attorney may be cause for a legal challenge by a disgruntled family member.

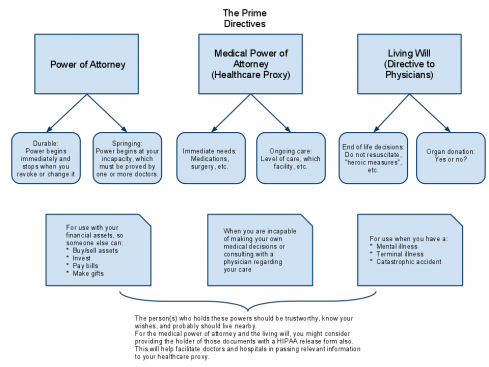

Here’s a chart to simplify things (click to enlarge).

Next week we will get a bit more personal, with some thoughts on what legacy you leave behind. In the mean time, if you would like more information on powers of attorney or health care directives, please contact The ACU Foundation. My email address is chris.sargent (at) acu.edu. Our toll-free phone number is 1-800-979-1906. Our services are completely confidential and completely free of obligation or monetary cost.

Disclaimer: All information on this blog is for educational purposes only. Employees of The ACU Foundation, and the writer of this blog specifically, are not attorneys and are not your adviser. Call us or come see us if you have any questions about this. See here for a more comprehensive (and more boring) version of this disclaimer.