College wasn’t for everyone and certainly not for someone like BT. He had barely any primary education to begin with, but BT was determined to one day go to college. He had his mind set on a school in Virginia which was considered a good distance in those days (about 500 miles) from his home in West Virginia. Lacking the resources necessary to pull off the trip, he went anyways, arriving a considerable time later at the college with 50 cents to spare. As soon as he could, BT went to enroll in classes. You can imagine the sight since BT hadn’t had a proper bath in weeks and was still in the same raggedy clothes he began his journey in. The schoolmaster was very reluctant, thinking BT was probably not capable or “worthy” of college admittance. After seriously considering saying no, she decided instead to give him an unorthodox test, asking him to sweep one of the nearby rooms of the college.

If you’re anything like me, you’re probably thinking, “Give the guy a break, don’t you know what he’s been through!” And what if you were in BT’s shoes, is it worth it for him at this point? Would you stoop to the level of sweeping a room? Then, think about what expectations you would have for what that room should look like. At best, after going through all of these challenges, if the guy does even a meager sweeping job, that’s enough, right? You can’t expect his best work now, can you? Let’s pick back up the story:

BT (or rather, Booker T. Washington) chronicles his thoughts in that moment by saying, “if I could only get a chance to show what was in me.” When given the opportunity (for that’s what he saw it as) to sweep this room, he said “never did I receive an order with more delight.” In other words, regardless of his circumstances, level of exhaustion, and hardships so far, he raised his expectations rather than lowered them. Here’s how Booker T. Washington remembers this in his classic autobiographical work, Up From Slavery:

I swept the recitation-room three times. Then I got a dusting-cloth and I dusted it four times. All the wood-work around the walls, every bench, table, and desk, I went over four times with my dusting-cloth. Besides, every piece of furniture had been moved and every closet and corner in the room had been thoroughly cleaned…She went into the room and inspected the floor and closets; then she took her handkerchief and rubbed it on the woodwork about the walls, and over the table and benches. When she was unable to find one bit of dirt on the floor, or a particle of dust on any of the furniture, she quietly remarked, ‘I guess you will do to enter this institution.’

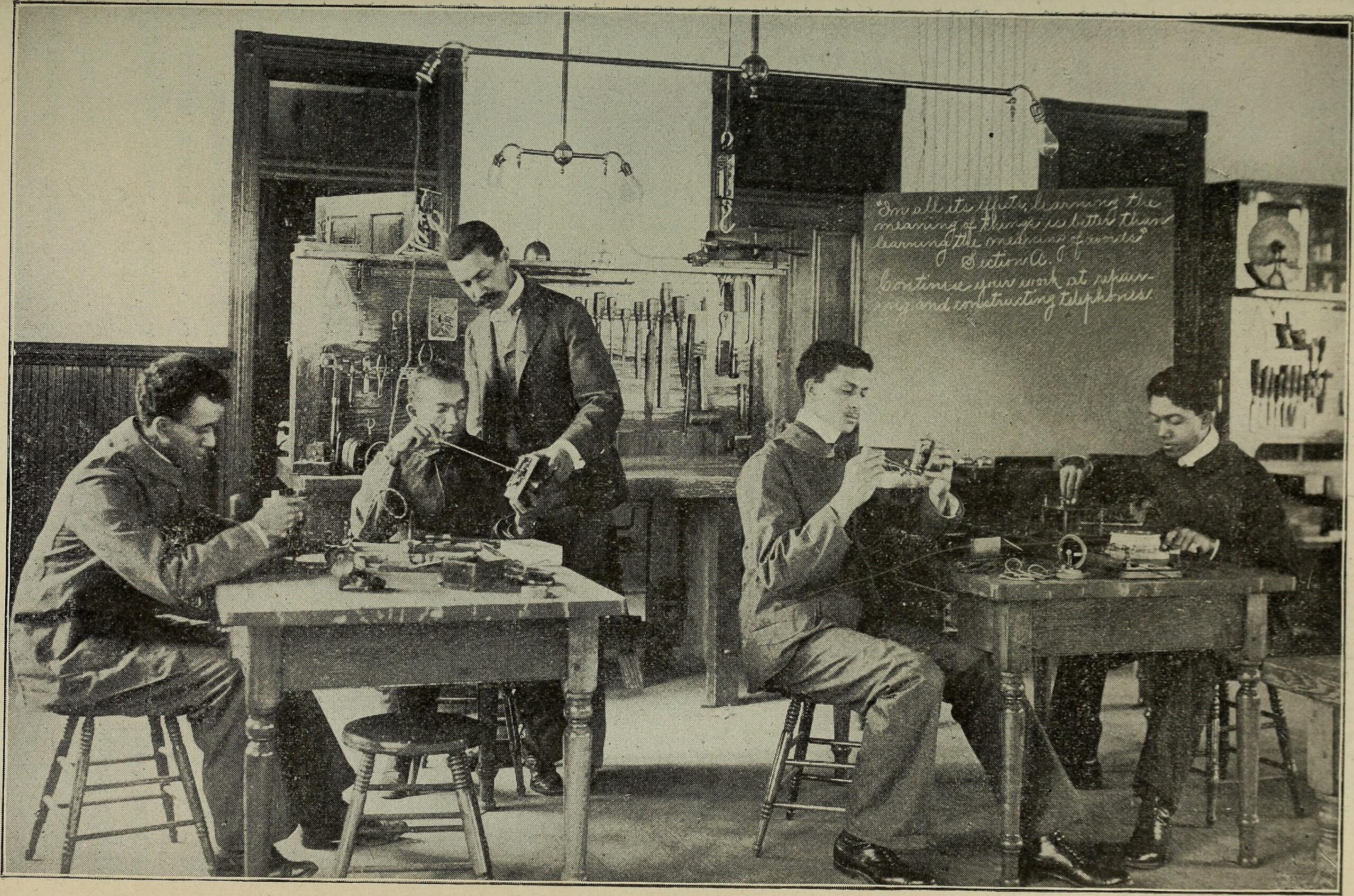

Booker T. Washington attended Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) circa 1870s

When Our Expectations Become Self-Fulfilling

In these perilous times of the COVID-19 global pandemic and more specifically the exceptional challenges it has created in academia, one can certainly sympathize with a desire for lowered performance expectations. How could we expect students or even professors to be doing their best work now? If people can just crawl across the finish line at this point, that’s good enough. In the midst of significant challenge, it only makes sense to lower our anticipation of what can really be accomplished. A significant body of research, however, suggests that we might be going at it all wrong. Perhaps it isn’t nearly as helpful as we think it is to decrease our performance standards when the environment poses greater risk and difficulty.

In 1928, sociologist William I. Thomas wrote, “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (The Child In America, p. 572). This sentiment was built on by Robert K. Merton in his seminal work entitled, “Self-Fulfilling Prophecy,” where he proposed that, “men respond not only to the objective features of a situation, but also, and at times primarily to the meaning this situation has for them. And once they have assigned a meaning to the situation, their consequent behavior and some of the consequences of that behavior are determined by the ascribed meaning” (Merton, 1948, p. 194). Merton explains this with an educational example of a student who feels like there is no way they will pass a test and spends most of his or her time worrying rather than studying, resulting in them doing poorly on the test.

Trouble at Oak Hill School

The dangers of the “self-fulfilling prophecy” emerged in a troubling fashion with the groundbreaking experiment at Oak Hill school published in 1966 by Rosenthal and Jacobson. In the study, the researchers tested students across eighteen classrooms at an elementary school in San Francisco. They shared the results of the tests with teachers highlighting that about 20 percent of the students showed promise for exceptional gains in intellectual growth. When the test was administered again about eight months later, the 20 percent of top students did in fact make exceptional gains in IQ compared to their non-exceptional peers and these effects persisted even to the second year of the study. The catch? The researchers didn’t actually share the objective test results at the beginning of the study, instead they simply chose 20% of the students at random and told the teachers that these students were exceptionally capable compared to their peers. The only difference between the top 20% and their peers was what the teachers believed to be true. And those beliefs resulted in consequences that were consistent with them. Teachers had higher expectations for those students in the 20%, and those expectations had real life impact.

One of my favorite extensions of this study was conducted by Eden and Zuk (1995) on Naval cadets. While nearly everyone is prone to some range of seasickness in their early naval training, the researchers set up an experiment to see if they might be able to change that. Cadets were randomly assigned to either an experiment or control group. Those in the experimental group were told that it was unlikely that they would get seasick, but if they did it probably wouldn’t affect their performance in the training. The control group was just given routine safety information. Results: those in the experimental group were significantly less likely to be seasick and had higher performance ratings from trainers than those in the control group. Eden and Zuk suggest that these messages (which they called “verbal placebos”) were effective because they raised the self confidence levels of the cadets and that heightened confidence resulted in the self-fulfilling prophecy. So the question is, what message are you sending yourself, your students, your kids?

Raising the Bar

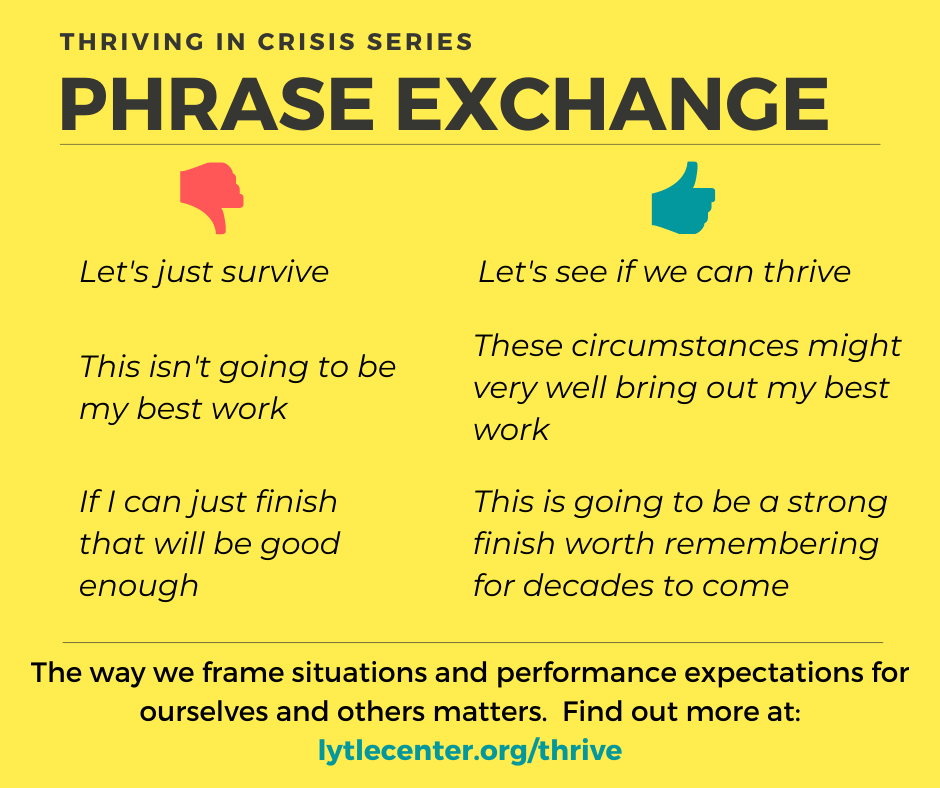

The way we frame situations and performance expectations for ourselves and others matters. It’s probably a good bet that if you tell your students you don’t expect them to be turning in their best work right now, they won’t be turning in their best work. But what if you told them instead, “this is a challenging circumstance and challenges present us with an opportunity to show what we’re made of – I know you have what it takes to turn in a top notch case analysis”? Perhaps that’s the confidence they needed to do something they will be proud of. Booker T. Washington had every right and excuse to do an average job of sweeping that room, but instead he did his best work and it was something he was so proud of that it made his autobiography decades later. What will we be telling our friends and loved ones about our work during this pandemic? Let’s speak and frame a narrative that makes it our best work!