With this post I launch an occasional series of reflections about what we do and how we do it. I’ll title these posts ‘Archives and Archiving’ and will from time to time write about how an archive operates. The inaugural installment is…processing. Processing collections is at the very heart of an archive.

‘Archival processing’ is a set of actions performed on a collection in order to gain intellectual and physical control of the objects and the information they contain. Here’s a good textbook definition:

Processing: “1. the arrangement, description, and housing of archival materials for storage and use by patrons.”

…

From Ford Motor Company: “A collective term used in archival administration that refers to the activity required to gain intellectual control of records, papers, or collections, including accessioning, arrangement, culling, boxing, labeling, description, preservation and conservation.”

–Richard Pearce-Moses*

*Moses, R. (2005). A glossary of archival and records terminology. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, p. 314.

The basic idea is this: What do I have, what is it about, and where can I find it? Answer these questions well and you have started down the road of processing that collection.

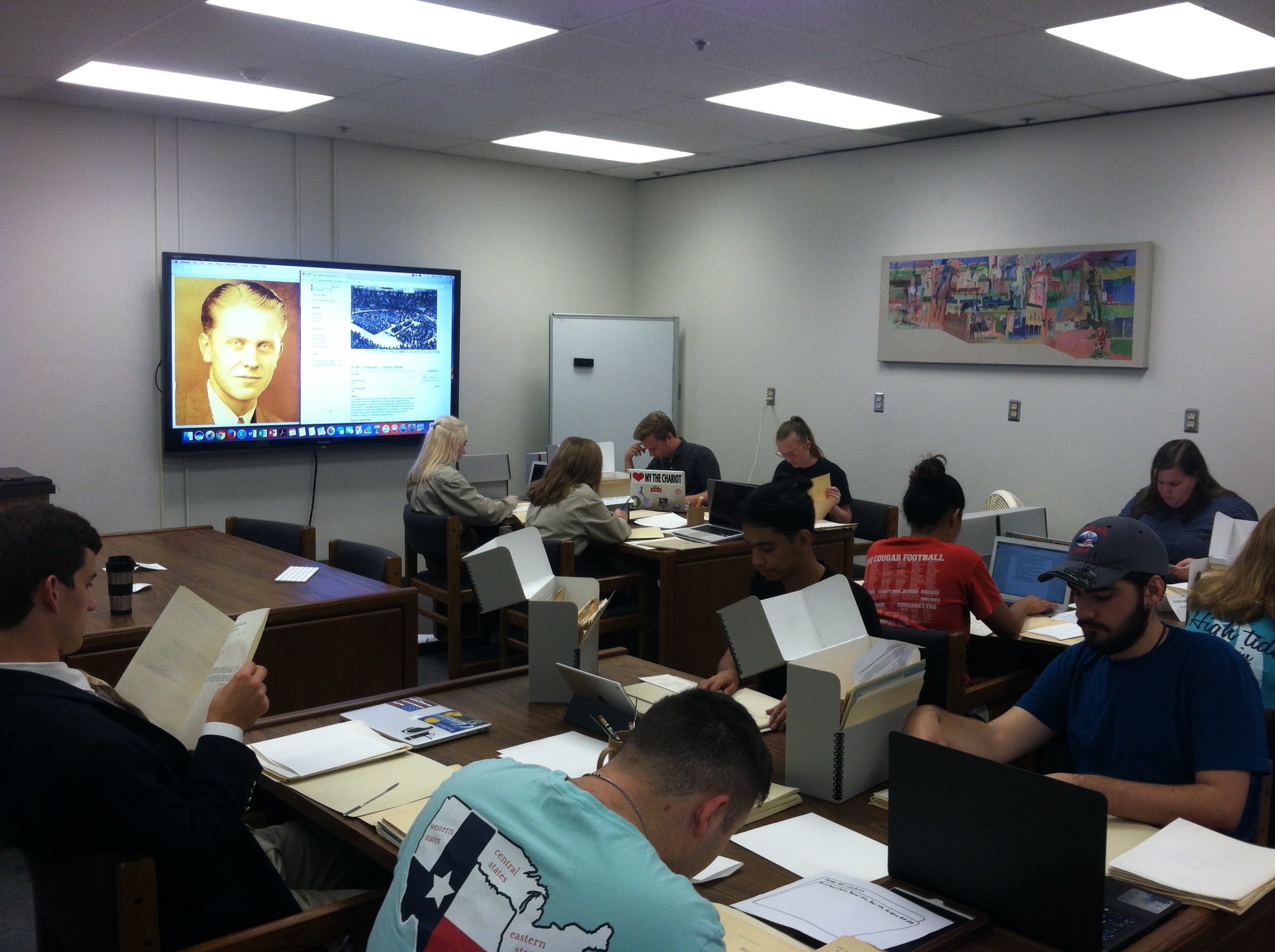

ACU history majors in Dr. Tracy Shilcutt’s HIST 353 (Historical Methods) course process the papers of longtime ACC president Don Morris. While they work the 1960 ACC Bible lectureship speech by Dr. Carl Spain, Modern Challenges to Christian Morals, plays in the background.

The size of the collection could be very small…a folder or two…or even a single item…or very large like the Herald of Truth Records at 406 linear feet (in 105 boxes). The collection could contain a single photograph, or a dimensional object, or a set of manuscript letters or diaries, or a series of institutional or organization records in file folders or notebooks. No matter the size, form, or contents, in broadest terms much of what happens in processing is very much the same across the board. In every case the objective is the same: we want to know what it is, what it is about, and where it is located or housed.

Until we have some answers to these questions the collection, practically speaking, is of little use to a researcher. If you, as the user of the archive, don’t know we have it, or can’t get to it, or can’t easily learn what is in the collection, you can’t make profitable use of the materials. However, knowing an archive has a collection, something of what it contains, and the archivist can reliably retrieve it (or you as the user can reliably and repeatedly retrieve items within it), then what a boon that is to your research project. That is the goal of processing: to put relevant materials within reach of the user. Or at least to put materials within reach and let the user determine relevancy and usefulness for their work. This needs to happen consistently and reliably for each collection; it also needs to happen across all collections in an archive.

The fuller definition Pearce-Moses uses above (from Ford Motor Company) captures the wide range of activities that feed into archival processing. It is appropriate to mention what is assumed to undergird this process. The prior assumption is that every archival repository operates from a set of core values, or at least an institutional charge or government mandate, that govern its collecting areas. Before anything is accepted into the archive it must first meet the collecting criteria. If it is outside of scope we decline the donation or assist the donor find a more suitable home. All things being equal and the materials are formally received into the archive (itself a separate set of actions called accessioning), the true work of processing begins.

A processed collection stands on two legs: arrangement and description. The materials must be arranged in some fashion, and that arrangement must be described. The materials themselves should also be described. For example, a minister donates to Center for Restoration Studies a large set of correspondence, sermon notes, ephemera, and photographs. The cardinal principle we follow is to maintain the creator’s arrangement of the material. Since the arrangement says something about the creator, we will maintain it. Some collections come to us in no order (I remember once about a decade ago opening a box to find a truly random stack of papers). In those cases we must impose an arrangement.

In our example, if the minister has kept correspondence in a certain way (chronological, or by sender, or some other discernible order) we will keep them as-is and describe accordingly. If it comes to us in chaos, we will sort it in a way that makes sense and enables a user to navigate through the materials. If a preacher worked through Biblical books in canonical order, and filed sermon notes accordingly, we will keep them just like that because the order reflects how those items were created and used and that is very important. Similar strategies will apply to the remainder of the collection. We will arrange this set of papers into four series: correspondence, sermon notes, ephemera, and photographs. We might further subdivide these series if needed or if the original arrangement demands it. Or we might decide this is sufficient to allow a researcher reasonable access, and let the motivated researcher take it from here. At this stage we will often rehouse materials into stable acid-free folders, sleeve photographs, or perform basic conservation techniques.

This might take a day or two for a small collection or several weeks for a large collection. Estimates vary about how long this should take, but all agree it takes time. Some estimate adequate processing should take 2-3 hours per cu. ft. box, other as high 8-10 hours per box. If items require extensive conservation it will require much more time. If the materials come to us in good order, processing time goes down. The opposite holds true for the rare cases when we receive materials in no discernible order.

No two collections are the same, but the goal is to achieve some level of knowledge about the contents of the collection, its arrangement, and order. The twin legs of arrangement and description give us something to stand on and by this point we have come a long way. Once a collection is processed we know (to some degree at least) what it contains and we can retrieve items from it easily and reliably and repeatedly. A corollary to ‘processing’ is ‘control.’ When we know what we have in a collection of papers and what it is about, we have achieved a certain kind of control over it: intellectual control. When we can gain physical access to it, be it at the collection level, or sometimes at the item level (or anywhere in between) we have achieved another kind of control: physical control.

The next step is to convey that information to our users in the form of ‘finding aids’ which are documents (paper or electronic) that render these kinds of knowledge available to users:

Finding aid: “1. A tool that facilitates discovery of information within a collection of records. 2. A description of records that gives the repository physical and intellectual control over the materials and that assists users to gain access to and understand the materials.”

“A finding aid is a single document that places the materials in context by consolidating information about he collection, such as acquisition and processing; provenance, including administrative history or biographical note; scope of collection including size, subjects, media; organization and arrangement; and an inventory of the series and the folders.

–Richard Pearce-Moses*

*Moses, R. (2005). A glossary of archival and records terminology. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, p. 168.

We use not one, but three methods to convey this knowledge to our users. The first is a library catalog record for the collection. This renders the collection visible to searchers looking in our online library catalog and globally through Worldcat.org. A second is through our online digital repository at digitalcommons.acu.edu. A third is through producing electronic documents (PDF format) that are also published on digitalcommons.acu.edu. To see examples of these, search our local library catalog and/or WorldCat for ‘Theophilus Brown Larimore Papers‘. You can search or browse ACU DigitalCommons and find the collection record that way, too.

There are multiple ways to process a collection. There are multiple components to the processing process: sometimes sequential, sometimes iterative, these steps come with a set of concerns, objectives, outcomes and ways of doing things. Each step or stage has options, and just as no two archival collections are the same, no two processing strategies need be the same. While there is a good bit of science here, much of it is an art. Part of this process is to determine the extent to which we should process a collection. How detailed must the arrangement and description be? How much do we need to learn or discover about a collection before we can call it processed? How much processing is sufficient to achieve access for the user? Who might use the collection? How much and what kind of processing is best, all things considered? All good questions, and all them and more are part of the process.

These approaches aim at different kinds of outcomes, each desirable in its own way according to its own rationale. We’ll cover some of those in future posts, with examples from the holdings of the Center for Restoration Studies. Stay tuned.