What does it mean to philosophize?

OUP’s Online Oxford Dictionary gives this definition: “speculate or theorize about fundamental or serious issues, especially in a tedious or pompous way.” If that’s what it means, most of us probably know people who fit the definition, though they may not be at the top of our dinner invitation list.

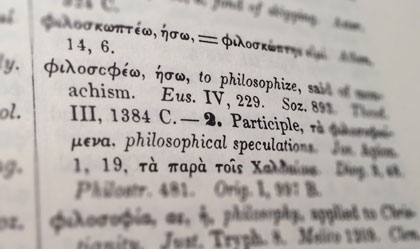

The term comes from the Greek philosophein, “to love knowledge, to study,” or “to teach philosophy.” But in the ancient world, it could also mean, “to lead a well-regulated life.” In his book, Philosophy as a Way of Life, Pierre Hadot masterfully explains the ways in which ancient philosophizing was as much about one’s commitment to particular ways of living as about engaging in philosophical discourse.

Early Christians picked up on this sense and amplified it. For instance, in his Exegetical Homilies on the Gospel of John, Chrysostom (ca. 349–407) uses words based on the root philosoph– over 200 times. The celebrated preacher of Antioch and Constantinople was fond of “philosophizing,” though he normally had something distinctly Christian in mind when he uses the term. “Philosophy is a great good!” he says (Homily 63.1). “That is, the philosophy that we have… true wisdom.”

The early Christian notion of what it means to philosophize comes out strongly when we look at the early Syriac translation of Chrysostom’s work. Since translators are trying to find the best possible ways to convey the meaning of their source texts in different languages, early translations can open windows onto the full breadth of meaning a term could have in its ancient context. Chrysostom’s Homilies were translated into the Aramaic dialect known as Syriac in the 5th century. The translator is very sensitive to the nuances of the Greek term “philosophize” as Chrysostom used it. Whenever Chrysostom uses the term in its intellectual and typically pagan sense, for Greek philosophers and their philosophical discourse, the translator is happy to use the Syriac loan word, pilasapha (or pilasupha), basically preserving a very Greek feel to the concept (e.g. Homily 2.2, 3; 17.4).

But when it comes to the practical virtues of the Christian life, a topic to which Chrysostom repeatedly returns often using the expression “philosophy,” the translator avoids Greek terminology and employs a host of Syriac moral terms instead. For instance, in various contexts the translator renders the term “philosophy” as:

- wisdom

- the fear of God

- endurance

- diligence

- all prudence

- self-control

In Homily 83, where Chrysostom mentions “the philosophy above,” the translator has “heavenly commitments.” In Homily 85, “to philosophize” is rendered with the Syriac, “to lust after heavenly things.”

It is unlikely that Chrysostom knew his Syriac translator, but if he had, he would have said, “That’s it! You got it!” True philosophizing is about living the Christian life, with wisdom and discipline. This sense of the term, so strongly evident in Chrysostom’s preaching, was sharpened and focused through the Syriac translator’s intuitive and flexible handling of the word.

Interesting post, thank you. I am curious what the actual Syriac terms are and detail about the translation. It would be interesting to see how different 5th century Syriac is from what we see in later classical works.

David, thanks for your interest! The post is more of an appetizer than a ful academic piece. A more detailed study is due to appear in the volume edited by H. Teule, et al., Syriac in its Multi-Cultural Context, scheduled to be released by Peeters later this year.