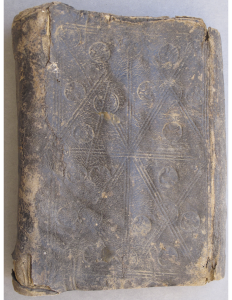

Manuscript Cover, Ethiopic Paul

Biblical manuscripts are not just depositories of texts, they are testaments to history. Each document has a story to tell, from the artisans who contributed the various components (pages of vellum or papyrus, decorations and art, book covers, cover designs, and bindings) and the original scribe (and sometimes the person who commissioned the book) to subsequent owners, readers, and editors, whether at home or in a monastery, whether in private or during worship. The scribbled notes, drops of candle wax, and smudges from unwashed hands all tell a rich, complex story.

In November 2017 CSART will host a webinar with Dr. Steve Delamarter entitled, “The Third Moment: Learning How to See Manuscripts with New Eyes.” The “third moment” is the moment of the book itself. In-between the moments of a text’s production and its reception by contemporary readers is the often lengthy and complex “moment” of its transmission as an object.

Bell Tower, St. Catharine’s

At ACU, professors and students are examining the rich history of documents from one of the most famous and oldest operating libraries of the world, thanks to the generosity of Father Justin, librarian for St. Catherine’s monastery at Mount Sinai. One manuscript only recently identified, is the oldest known copy of Paul’s letters in the Ge‘ez language (classical Ethiopic). As important as the document is to the history of the New Testament text, it has other stories to tell.

Because large portions at the beginning and end of the manuscript have been lost, we do not know much about where it was written. Nevertheless, we know that it was treasured. Notes added to the remaining portions of the codex provide windows into the heart of some of its owners the book has had over the years.

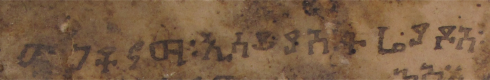

The first to lay claim was a Greek speaker, whose name was apparently Isaias Triados.

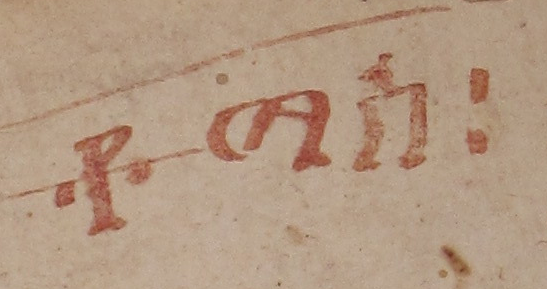

Isaias Triados

In the top margin of the first extant page he writes a Greek phrase using Ge‘ez letters. With no attempt at false humility he proclaims, “Great is the name of Isaias Triados” (μεγα τ᾽ονομα Ησαιας Τριαδος). We can only hope that he was referring to another entity, either a person such as a good friend or favored church, rather than to himself.

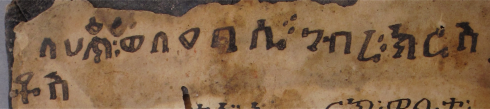

In contrast to this potential self-aggrandizement by one owner, the next owner more humbly enters on the next page: “[This is the property] of the sinner and transgressor Gabra Krestos.”

The Sinner Gabra Krestos

His attachment to the codex is expressed at the bottom of the same page: “If this book were not mine, I would have no other consolation.” Later in the book he asks for prayers from those who might encounter the book in the future.

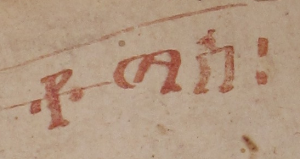

Tomas

Another person, Tomas, left evidence of his presence. In a well trained hand he inscribes his name in red ink at the top of a randomly chosen page. It is as if a traveler left graffitti, hoping to be remembered by those who would visit the same treasured spot in the future.

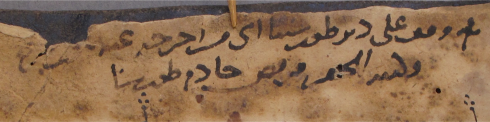

Finally we have the note of Marqos, who tells us in Arabic that the manuscript was donated to the monastery at Mt. Sinai. This same Marqos has inscribed other books donated to the monastery, so he probably served as a librarian. Thankfully in this manuscript he does not add the threat of excommunication from the church and from God’s glory for anyone who steals the book – a threat he makes elsewhere.

Marqos’s acquisition note

This remarkable book is not only a crucial witness to the text of St. Paul’s Epistles; it is a testament to many chapters of the complex history of those who owned and used the book. For some time the document sat in obscurity, stored with a number of other books in disrepair in the tower of St. George. In the mid 1970s, though, the floors of that tower collapsed during an earthquake, with the document thankfully being rescued in the process of cleaning up. It is certainly a document with much more history ahead of it as it will be the object of study for decades and perhaps centuries to come.

Recent Comments