The Don Heath Morris Presidential Records (1942-1974) are processed and ready for researchers. The finding aid for the papers is now available on our institutional repository. These papers include 80 linear feet (190 boxes) of correspondence and topical files generated, compiled, and utilized by Don Heath Morris in the course of his duties as President of Abilene Christian College.

Dr. Don Heath Morris earned his education degree at Abilene Christian College. As a student, he served as president of his class; edited the school yearbook, the Prickly Pear; and participated in intercollegiate debate, never losing a decision. After graduation, he taught and coached debate at Abilene High School. He returned to Abilene Christian in 1928 as a speech teacher. In four years, he rose to the vice presidency. From 1932-1940, he was vice president and head of the Department of Speech. Morris was the first former student to become president of Abilene Christian College. He served 29 years, and in 1969 ranked as the dean of college and university presidents in Texas, having served the longest in the chief executive’s position. He received three honorary doctorates from other Christian colleges before his retirement in 1969. After retirement, Morris was appointed the first Chancellor and remained active in campus life. He died suddenly on January 9, 1974, suffering a heart attack while walking from Moody Coliseum back to his office in Brown Library. His Presidential papers remained as he left them, and we transferred into the University Archives shortly after his death. [Adapted from https://www.acu.edu/about/past-present-future/leadership.html. Accessed 19 August 2020]

Photo of Walter Adams (Dean), Don Morris (President), and Lawrence Smith (Bursar) sitting on a couch with Walter Adams getting ready to sign something. There are flowers on the middle of the table and a Bible is in front of Lawrence Smith. Ca. 1965. From the Jesse P. Sewell Photograph Collection: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/sewell_photos/837/

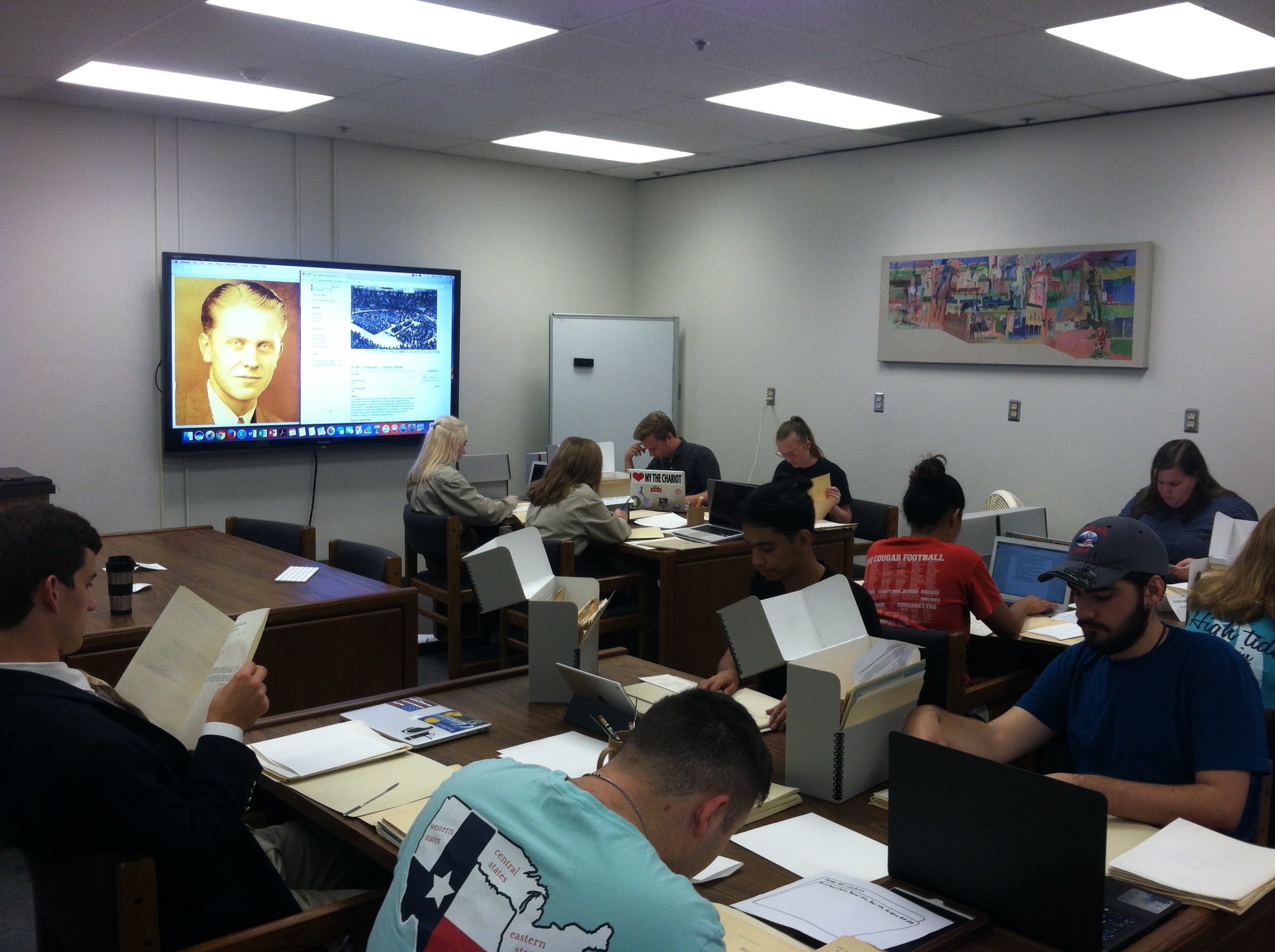

This processing of the Morris Papers began through partnership with Dr .Tracy Shilcutt, Professor of History, and successive classes of her students in HIST 353: Historical Methods. These students worked under the supervision of Special Collections staff Chad Longley, Ron Longwell, Carisse Berryhill, Amanda Dietz, and McGarvey Ice. Students refoldered the collection into acid-free folders, generated the folder-level description, while gaining hands-on experience in archival theory and practice as part of their training in historical methodologies.

ACU history majors in Dr. Tracy Shilcutt’s HIST 353 (Historical Methods) course process the papers of longtime ACC president Don Morris. While they work the 1960 ACC Bible lectureship speech by Dr. Carl Spain, Modern Challenges to Christian Morals, plays in the background.

Photo of the Sub-T 16 Social Club:top row-Walter Adams, Raymond Simcox, A.C. Hill, Wendell Bedicheck, Aubrey Pete Banowsky, Jack Meyer, John Paul Gibson, Lowell Whimbush, J.C. Brown. second row-Oscar Kelley, Ernest Wells, Rupett Watson, Ernest Witt, Frank Kerchville, Albert Wall, Don Morris. From the Jesse P. Sewell Photograph Collection: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/sewell_photos/392/

Additional materials by or about Don Heath Morris:

–Don Heath Morris, “Moral responsibilities of Christian Leadership,” 1963 Abilene Christian College Lectureship

—Owen Cosgrove interview with J. W. Treat. Oral history interview on cassette dated 29 August 1975. Owen Glen Cosgrove interviewed J. W. Treat, head of the Language Department at Abilene Christian College. Cosgrove chose to interview Treat because he roomed with President Don Morris while they were doing graduate work at the University of Texas and because they worked together at Abilene Christian College for thirty-five years.