Each month I have checked in here to provide updates about the growth and development of our print collections. We steward several print collections of books, periodicals (both bound and loose issues), tracts, and pamphlets. We also catalog audio, video, and digital materials in several formats which were/are published or otherwise widely distributed; nearly all of them are either produced by the University or are Stone-Campbell-related. These are discoverable through the online library catalog. As an aside, we have tens of thousands of A/V items (reels and cassettes, mostly) in our archival collections. These items are usually not published or mass-produced, such as sermons delivered at congregations. These are discoverable, in varying degrees, through the finding aids we create for each collection.

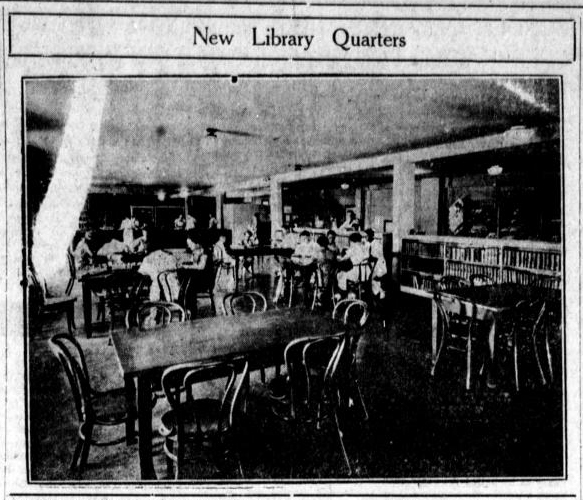

‘New Library Quarters’ from The Optimist, February 25, 1937. Available at: https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth101341/m1/3/

In nearly every case, when we add items to print collections, the new catalog records are also pushed over to Worldcat so they are globally discoverable. Many of the Stone-Campbell items we preserve have never been cataloged before, so each month in my blog posts I call attention to how original cataloging is a tremendous contribution to knowledge about information resources from and about the Stone-Campbell Movement. Additionally, I am always looking out for variant editions and printings of Stone-Campbell items so our collection represents the full breadth of our publishing activities. These variations are also noted in the catalog records.

As we begin 2021, with great thanks to our colleagues and student workers in Technical Services, we can reflect on the addition of 2,749 items* to our print collections. Thank you to Gary Oliver for his work with original cataloging, to Shan Martinez who creates multiple hundreds of records and supervises several students, and volunteer Linda Foster who has faithfully created records for thousands of tracts (with thousands more to go). Shan’s work in 2020 is especially significant in that she cataloged almost 400 boxes worth of unbound periodicals this past year.

*Some of these ‘items’ in my monthly lists are in reality only the titles of items which in the case of loose periodical issues represent many, many (many) more ‘items’ than might be readily apparent. Unbound periodical issues present a storage and cataloging challenge. We store them in boxes (often multiple titles in a single box when we only have a few issues of a title), number the boxes, and when the box contents are cataloged, these box numbers function like a call number. The boxes vary in size (about 10 x 13 x 4 in thick) to bankers boxes and a few larger boxes here and there. The cataloging work involves collation of issues, arrangement, storage, and description, so there is quite a bit more work to cataloging these than you might realize. Mac and student workers accomplished much of this, but Shan’s work at the point of cataloging is an added layer of verification. In 2020 we began at box 404 and now are filling box 790 for the cataloged titles. Also in early 2020 we completed a pre-sort and arrangement of an additional 200 bankers boxes of loose uncataloged periodicals and church bulletins that we will catalog. By the way. some bulletins (single issues especially) are not cataloged but are filed in the Congregational Vertical File. At this rate, it is entirely possible that the remaining 200 bankers boxes of loose unbound periodicals will be finished in 2021. Of course, we hope to acquire more and are perfectly content knowing the work will never truly be ‘finished.’

Here are the breakdowns of the number of items added by month in 2020. If you’d like to see the titles and authors, browse these lists.

January: 185

February: 212

March: 404

April: 391

May: 230

June: 362

July: 139

August: 185

September: 181

October: 167

November: 135

December: 58

In order to prepare new items for our colleagues in Technical Services, I determine whether the item is within our collecting scope. If not it goes to our colleagues for evaluation for possible addition to the circulating collection. But if it is in scope, a student worker (I do this often, too) verifies whether we have the item already cataloged. If not, we add it to the workflow to be cataloged. If we already have a copy I compare its condition against the one on the shelf. I also look for variant editions, printings, bindings, or other features (such as an author’s signature or gift inscription) that merit inclusion or a special note. If the new book is in better condition that the shelved copy, I replace the worn copy. If it is in comparable condition, it might go in the queue for scanning or digitization, or I offer it for the circulating collection, or trade to another library. We then take the items upstairs to Technical Services along with instructions for catalogers: where it should be cataloged (into the CRS collection or another sub-collection within rare books), who the donor is, and whether cataloging should make special note of any edition or printing or provenance. When the catalogers finish, our student workers lead the way in making sure items are shelved, and I or Amanda assist when needed.

Not only do these 2,749 new (and new-to-us) titles represent the fine cataloging work of our colleagues and their staff, they represent dozens of donors who wanted to see the collection grow in scope, utility, breadth, and depth. We do not yet know how students and researchers will utilize these materials, but we look forward to the contribution they will make to our history. And we look forward to what 2021 will bring to the shelves.