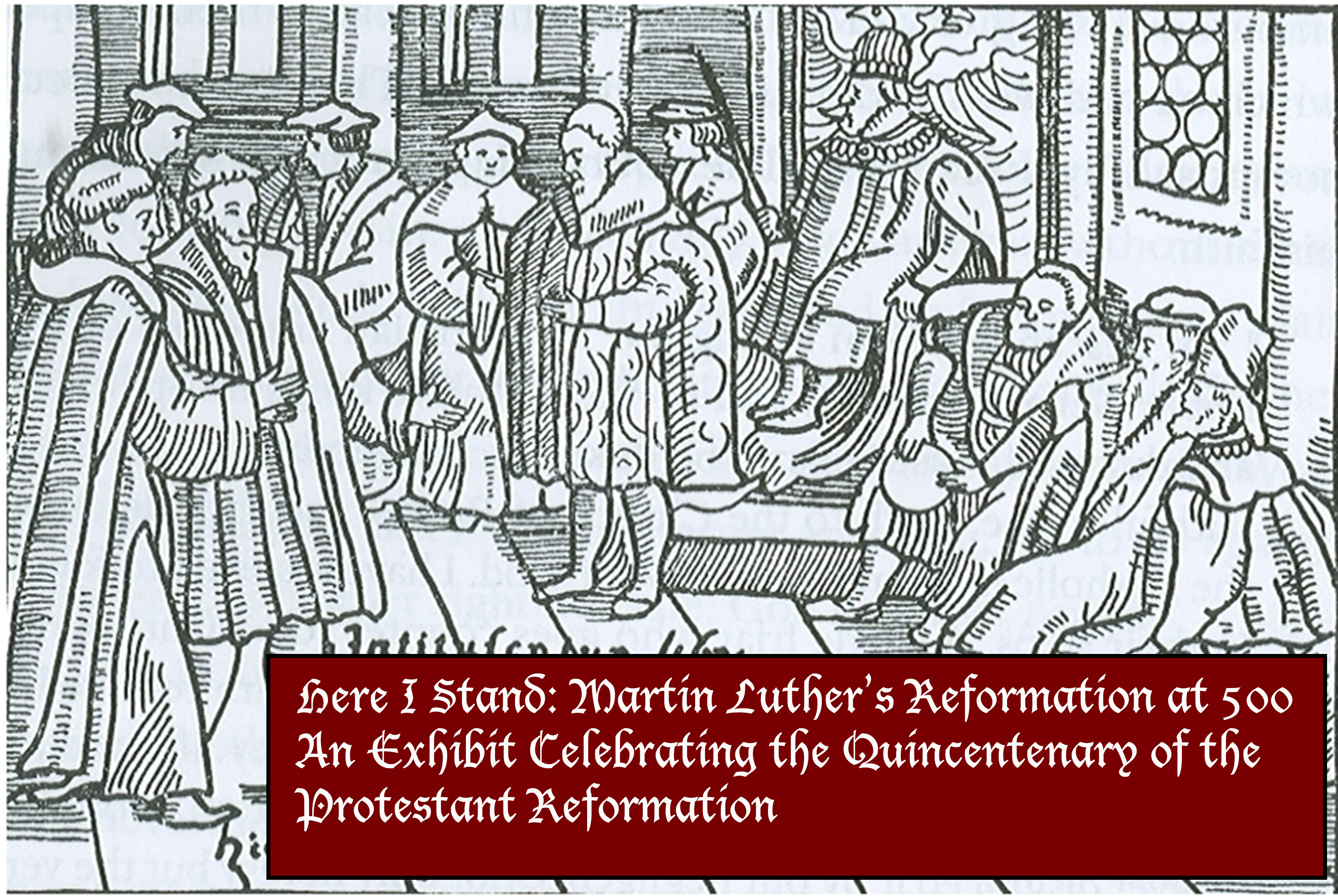

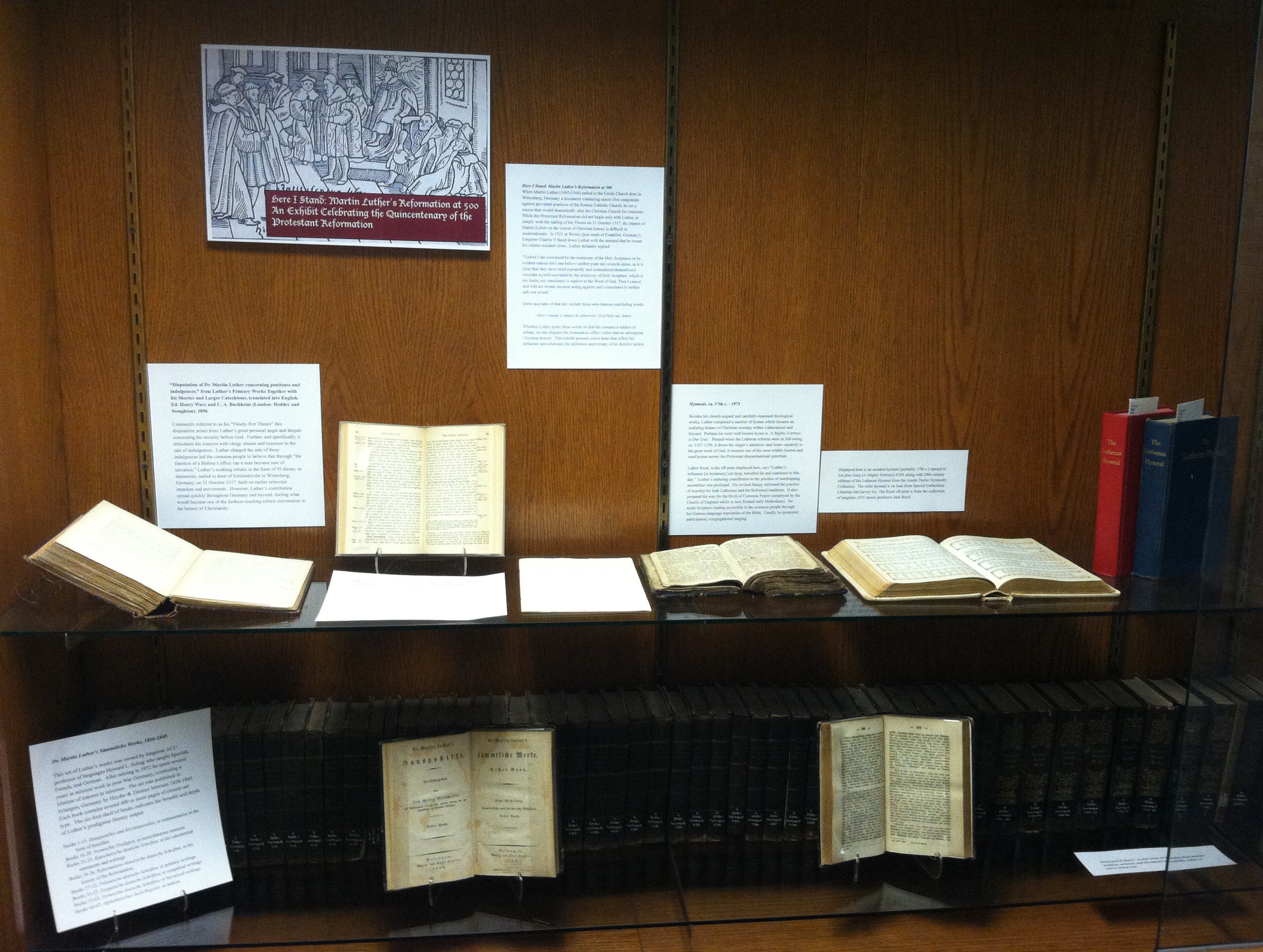

Here I Stand: Martin Luther’s Reformation at 500, An Exhibit Celebrating the Quincentenary of the Protestant Reformation

When Martin Luther (1483-1546) nailed to the Castle Church door in Wittenberg, Germany a document containing ninety-five complaints against prevalent practices of the Roman Catholic Church, he set a course that would dramatically alter the Christian Church for centuries. While the Protestant Reformation did not begin only with Luther, or simply with the nailing of his Theses on 31 October 1517, the impact of Martin Luther on the course of Christian history is difficult to underestimate. In 1521 at Worms (just south of Frankfurt, Germany), Emperor Charles V faced down Luther with the demand that he recant his reform-minded views. Luther defiantly replied:

“Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Holy Scriptures or by evident reason-for I can believe neither pope nor councils alone, as it is clear that they have erred repeatedly and contradicted themselves-I consider myself convicted by the testimony of Holy Scripture, which is my basis; my conscience is captive to the Word of God. Thus I cannot and will not recant, because acting against one’s conscience is neither safe nor sound.”

Some accounts of that day include these now-famous concluding words:

Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise. God help me. Amen.

Whether Luther spoke these words on that day remains a subject of debate, no one disputes the tremendous effect Luther had on subsequent Christian history. This exhibit presents select items that reflect his influence and celebrates the milestone anniversary of his decisive action.

This online exhibit showcases the physical exhibit displayed on the lower level of ACU Brown Library during the fall semester 2017.

Left case:

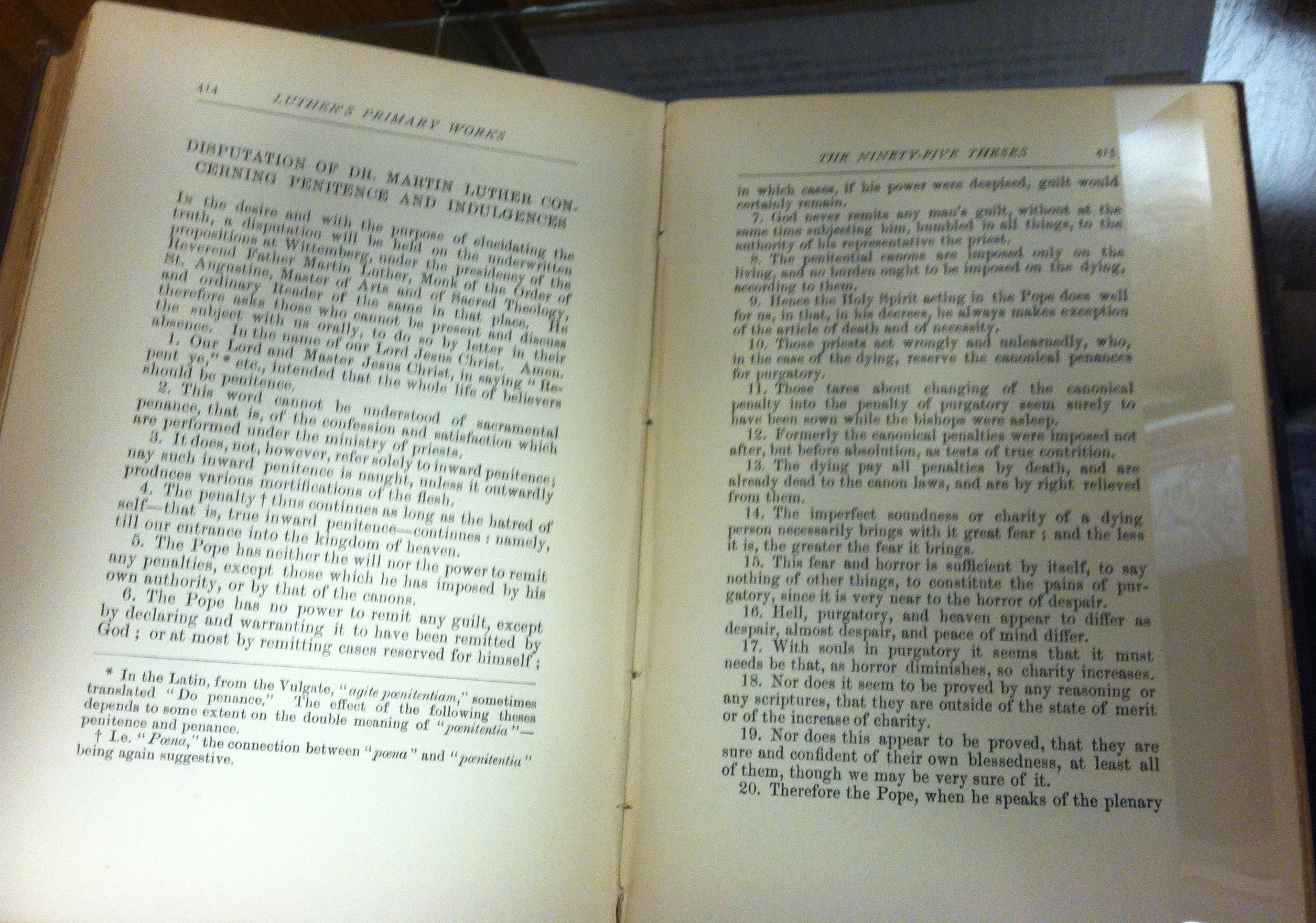

“Disputation of Dr. Martin Luther concerning penitence and indulgences,” from Luther’s Primary Works Together with his Shorter and Larger Catechisms, translated into English. Ed. Henry Wace and C. A. Buchheim (London: Hodder and Stoughton), 1896.

Commonly referred to as his “Ninety-five Theses” this disputation arises from Luther’s great personal angst and despair concerning his security before God. Further, and specifically, it articulates his concern with clergy abuses and excesses in the sale of indulgences. Luther charged the sale of these indulgences led the common people to believe that through “the function of a Bishop’s office can a man become sure of salvation.” Luther’s scathing rebuke in the form of 95 theses, or statements, nailed to door of Schlosskirche in Wittenberg, Germany, on 31 October 1517, built on earlier reformist impulses and movements. However, Luther’s contribution spread quickly throughout Germany and beyond, fueling what would become one of the farthest-reaching reform movements in the history of Christianity.

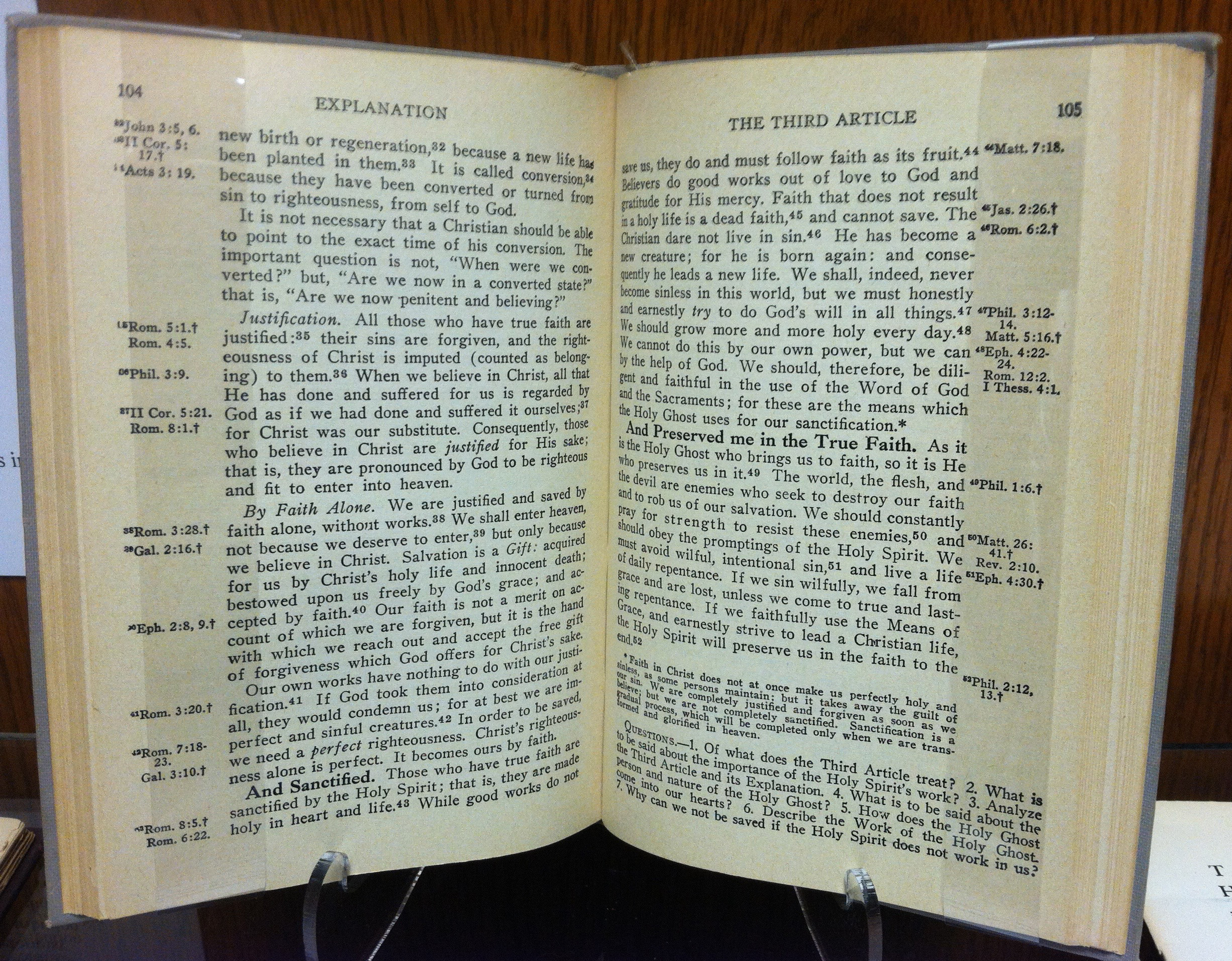

John Stump, An Explanation of Luther’s Small Catechism. A Handbook for the Catechetical Class. (Philadelphia: The United Lutheran Publication House), 1935

“Since the task of the pastor in catechization,” Stump writes, “is not only to impart religious instruction, but to impart it on the basis of that priceless heritage of our Church, Luther’s Small Catechism, the explanation here offered follows the catechism closely. The words of the catechism are printed in heavy-faced type and are used as heading wherever possible; and this the words of the catechism may be traced as a thread running through the entire explanation.”

Designed for use in congregational class settings as well as private study, it is opened to a section describing the classic Reformation doctrine of sola fide or justification by faith alone.

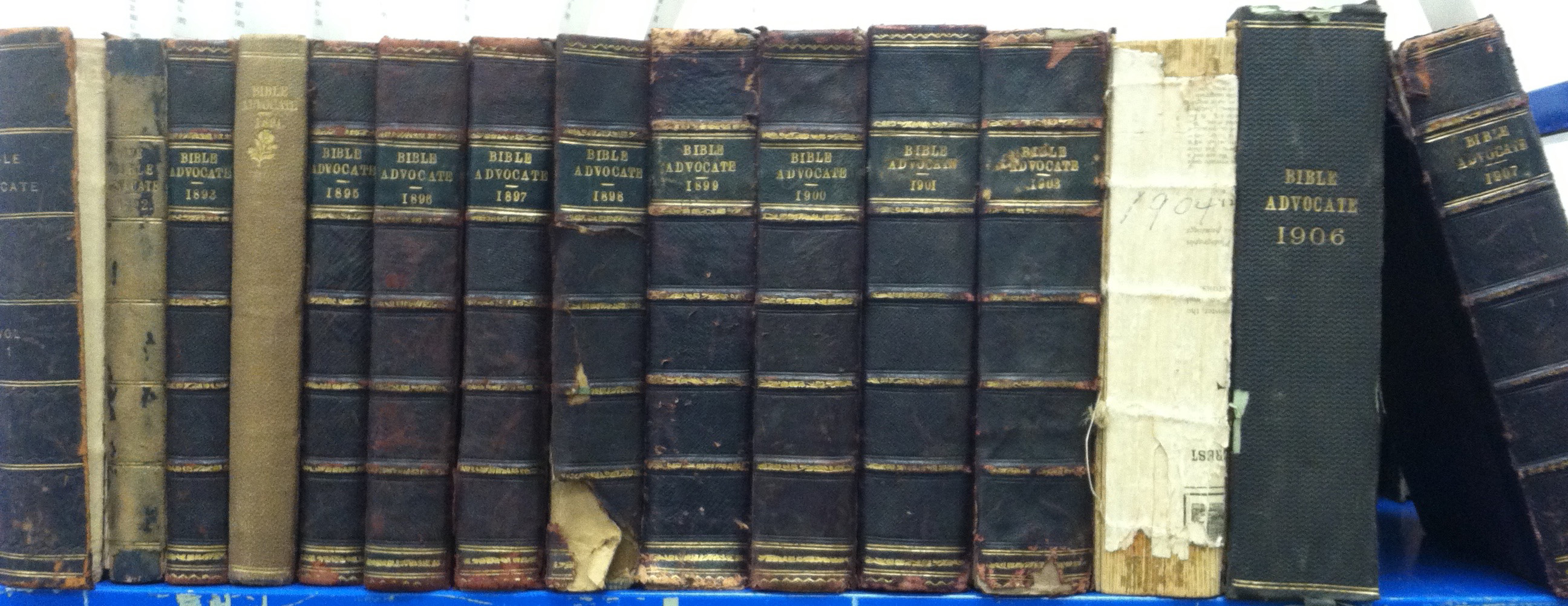

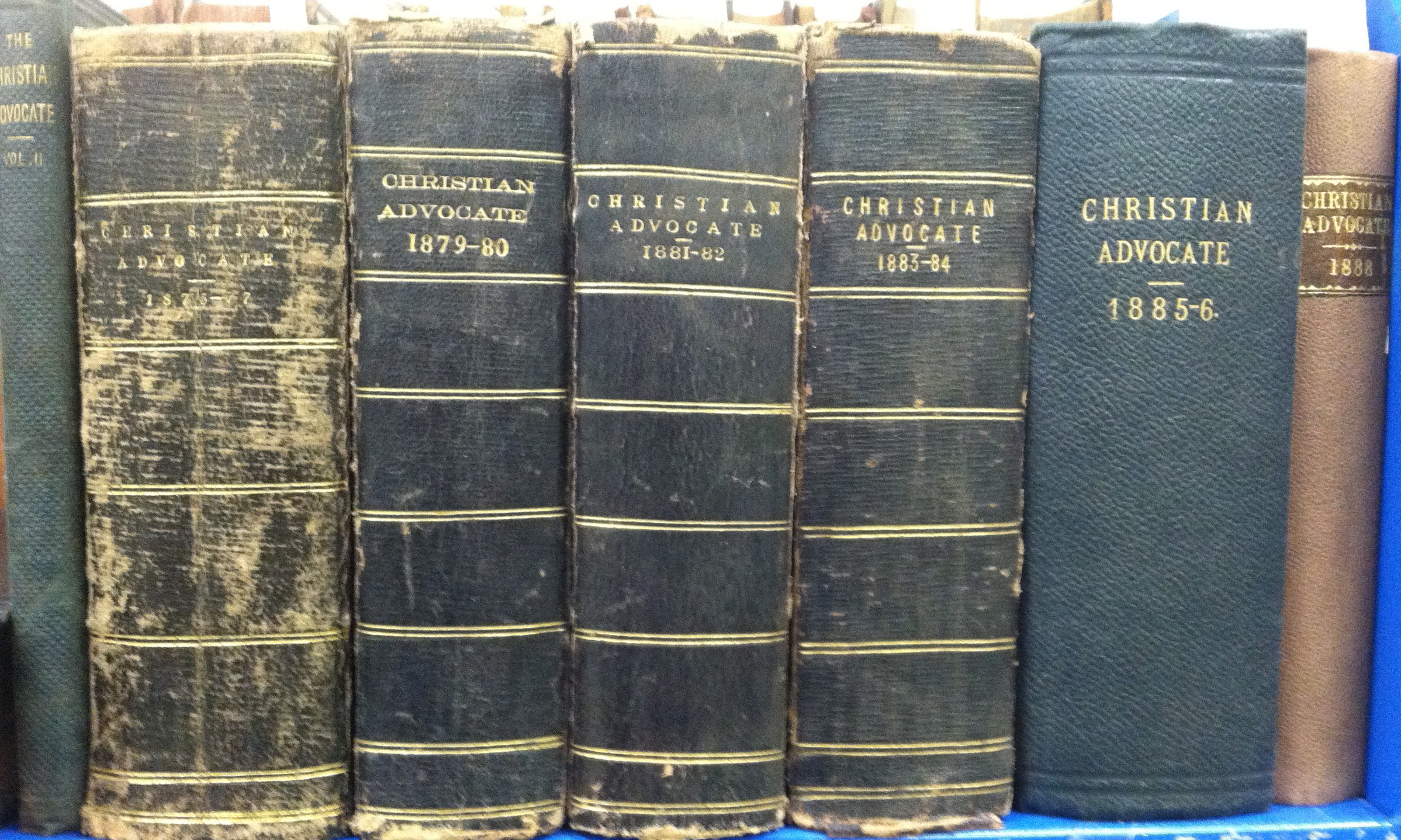

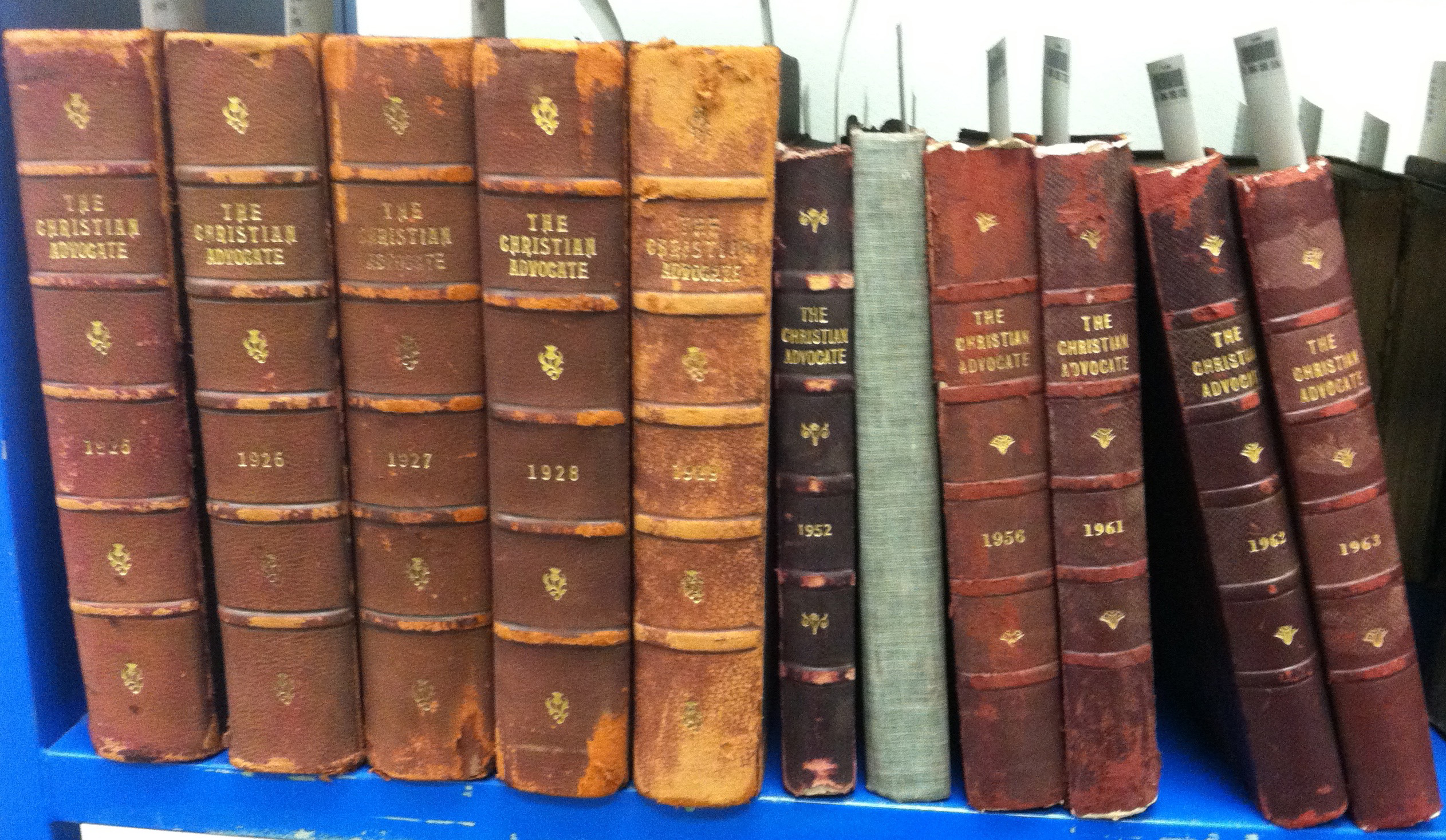

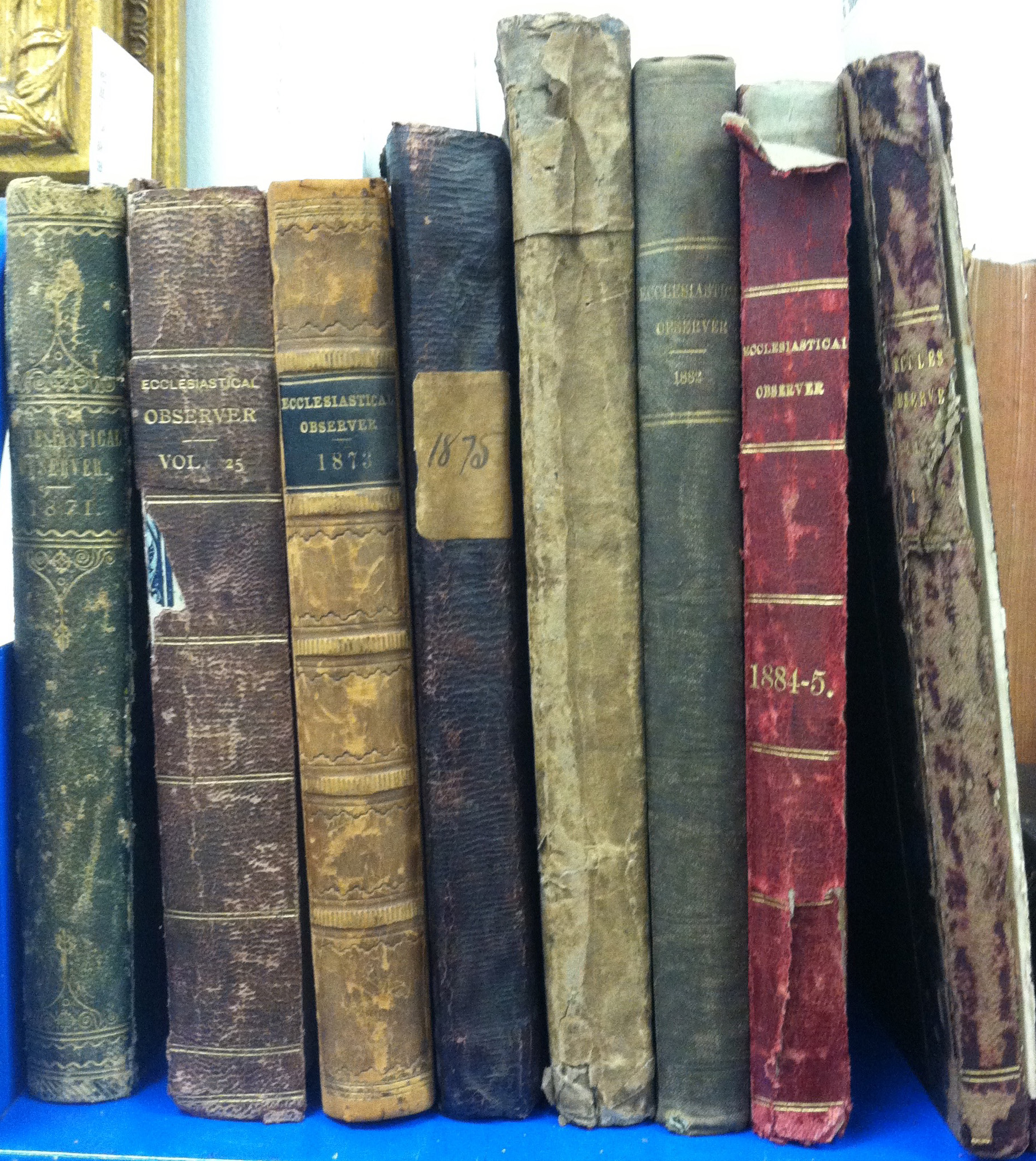

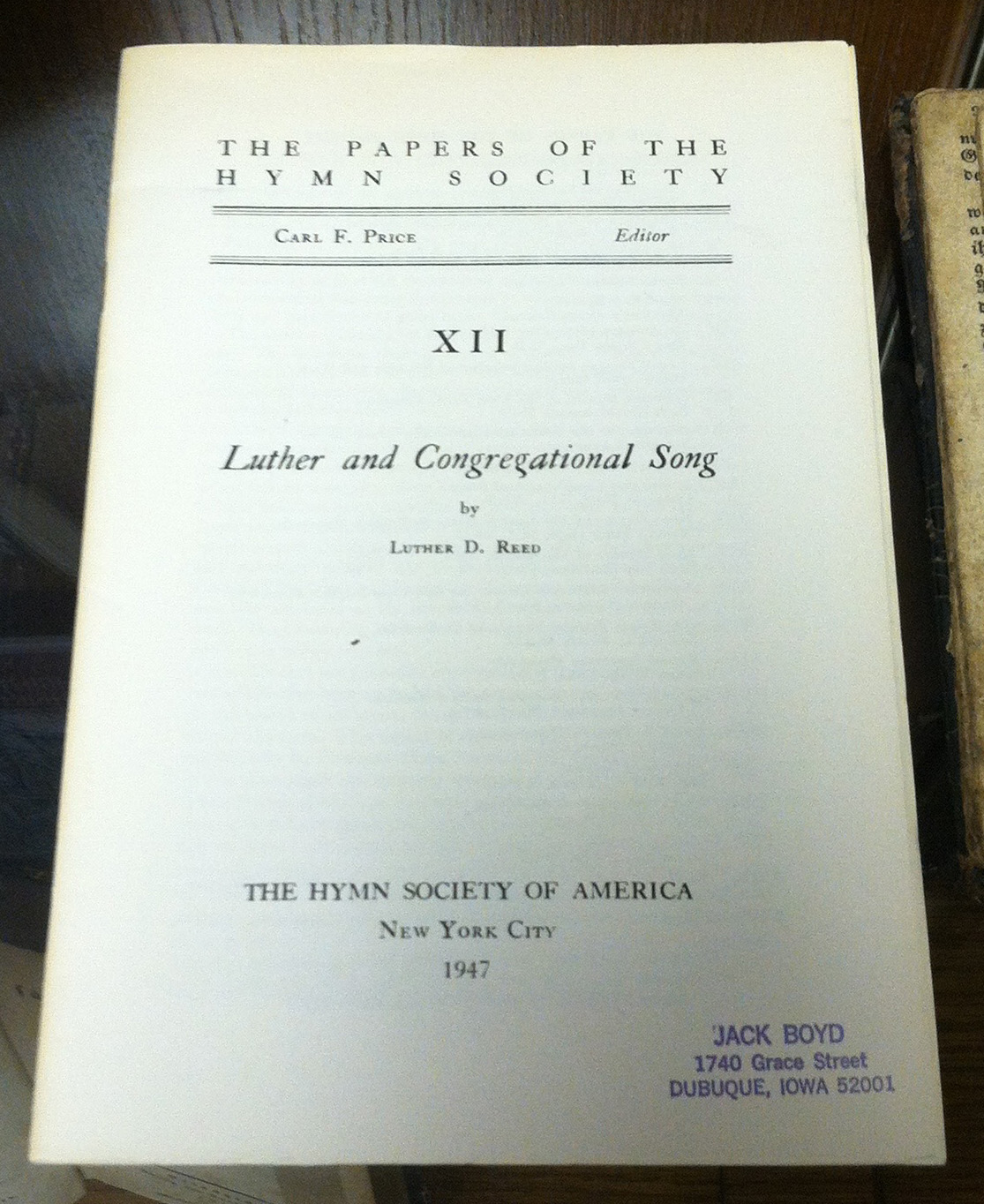

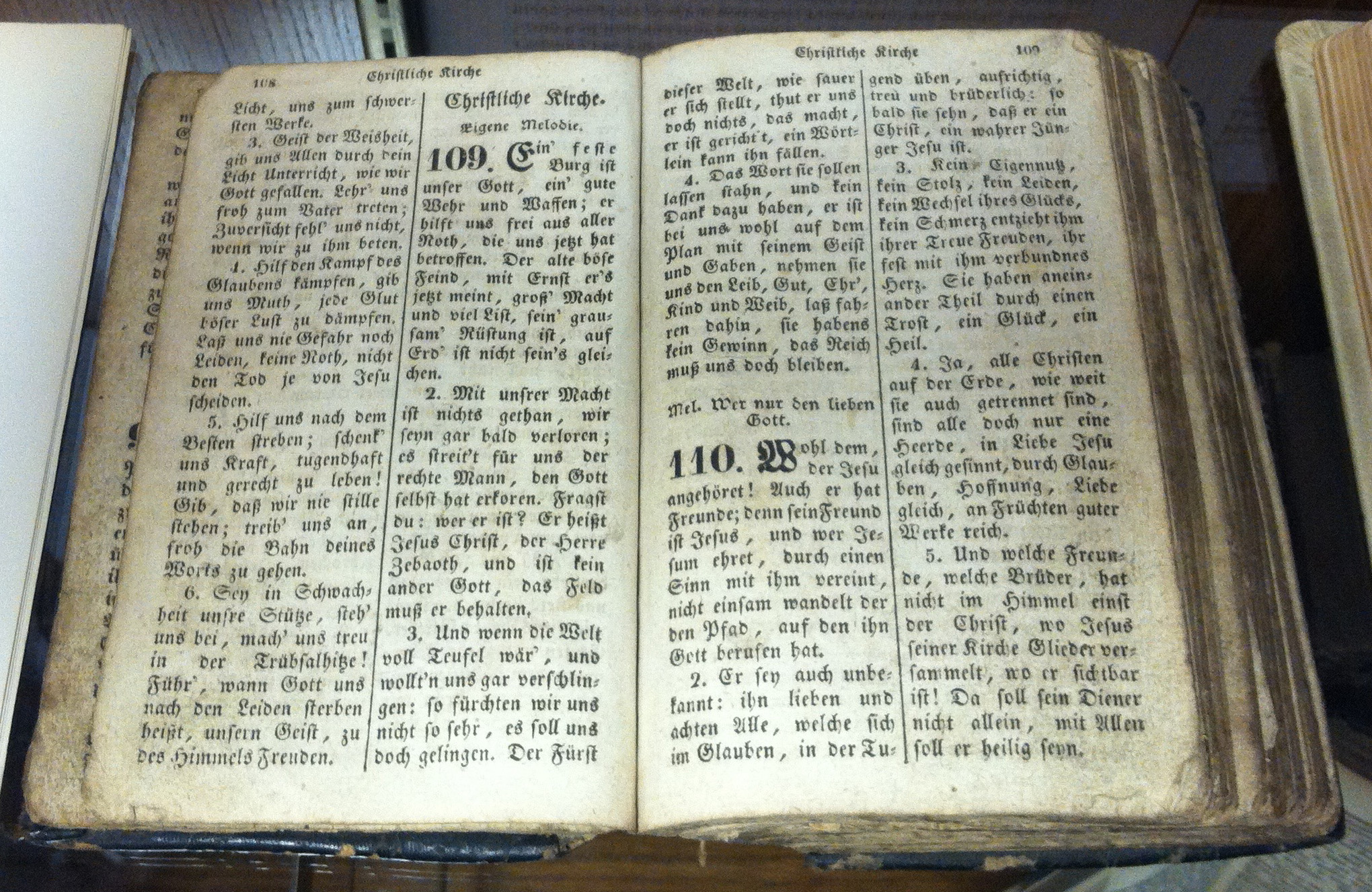

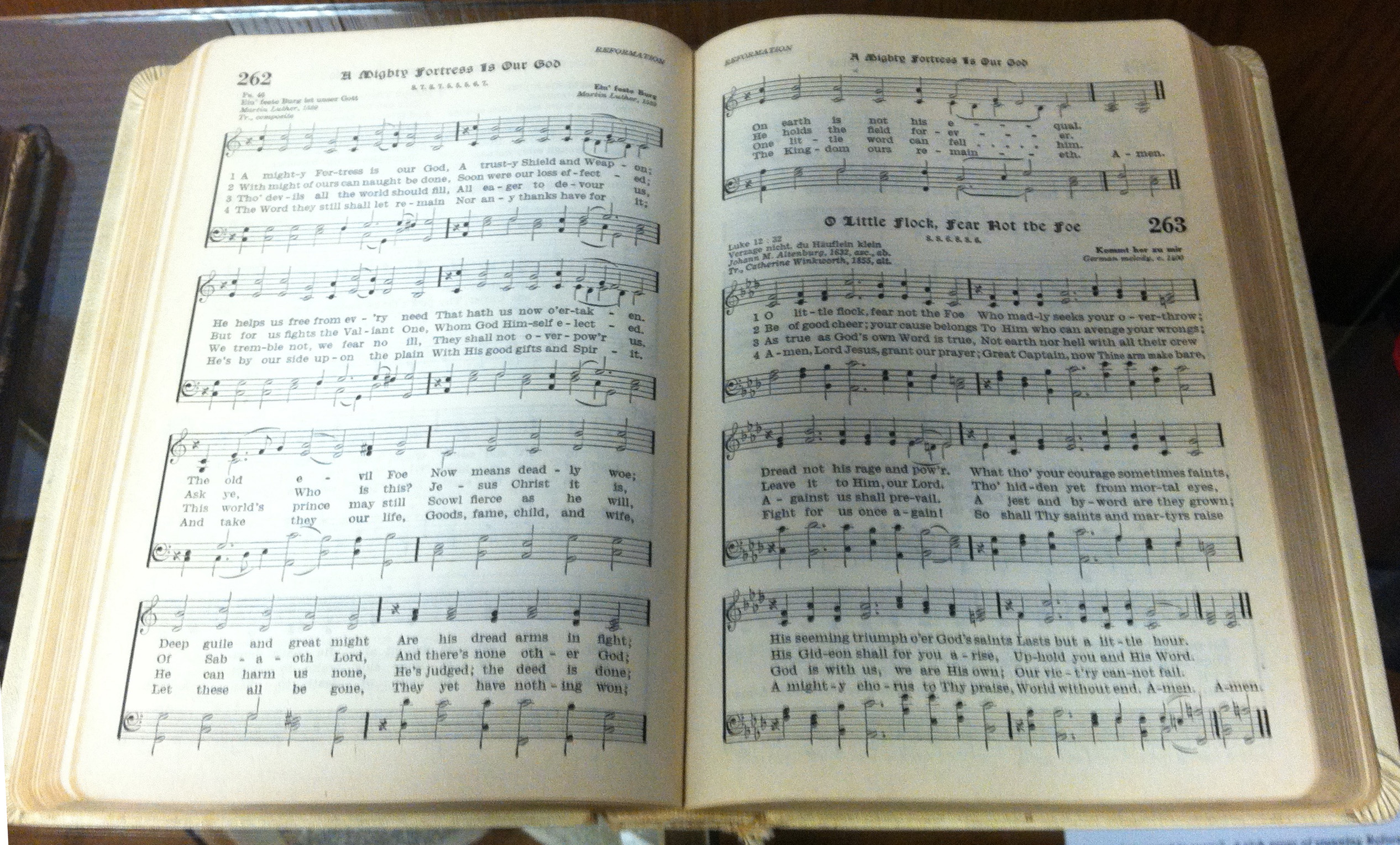

Hymnals, ca. 17th c. – 1973

Besides his closely-argued and carefully-reasoned theological works, Luther composed a number of hymns which became an enduring feature of Christian worship within Lutheranism and beyond. Perhaps his most well-known hymn is ‘A Mighty Fortress is Our God.’ Penned when the Lutheran reforms were in full-swing ca. 1527-1529, it draws the singer’s attention–and hope–squarely to the great work of God. It remains one of the most widely-known and used hymns across the Protestant denominational spectrum.

Luther Reed, in the off-print displayed here, says “Luther’s influence [in hymnody] cut deep, travelled far and continues to this day.” Luther’s enduring contribution to the practice of worshipping assemblies was profound. His revised liturgy informed the practice of worship for both Lutherans and the Reformed traditions. It also prepared the way for the Book of Common Prayer (employed by the Church of England which in turn formed early Methodism). He made Scripture reading accessible to the common people through his German-language translation of the Bible. Finally, he promoted participatory congregational singing.

Displayed here is an undated hymnal (probably 17th c.) opened to Ein feste burg (A Mighty Fortress) #109, along with 20th century editions of the Lutheran Hymnal from the Austin Taylor Hymnody Collection. The older hymnal is on loan from Special Collections Librarian McGarvey Ice. The Reed off-print is from the collection of longtime ACU music professor Jack Boyd.

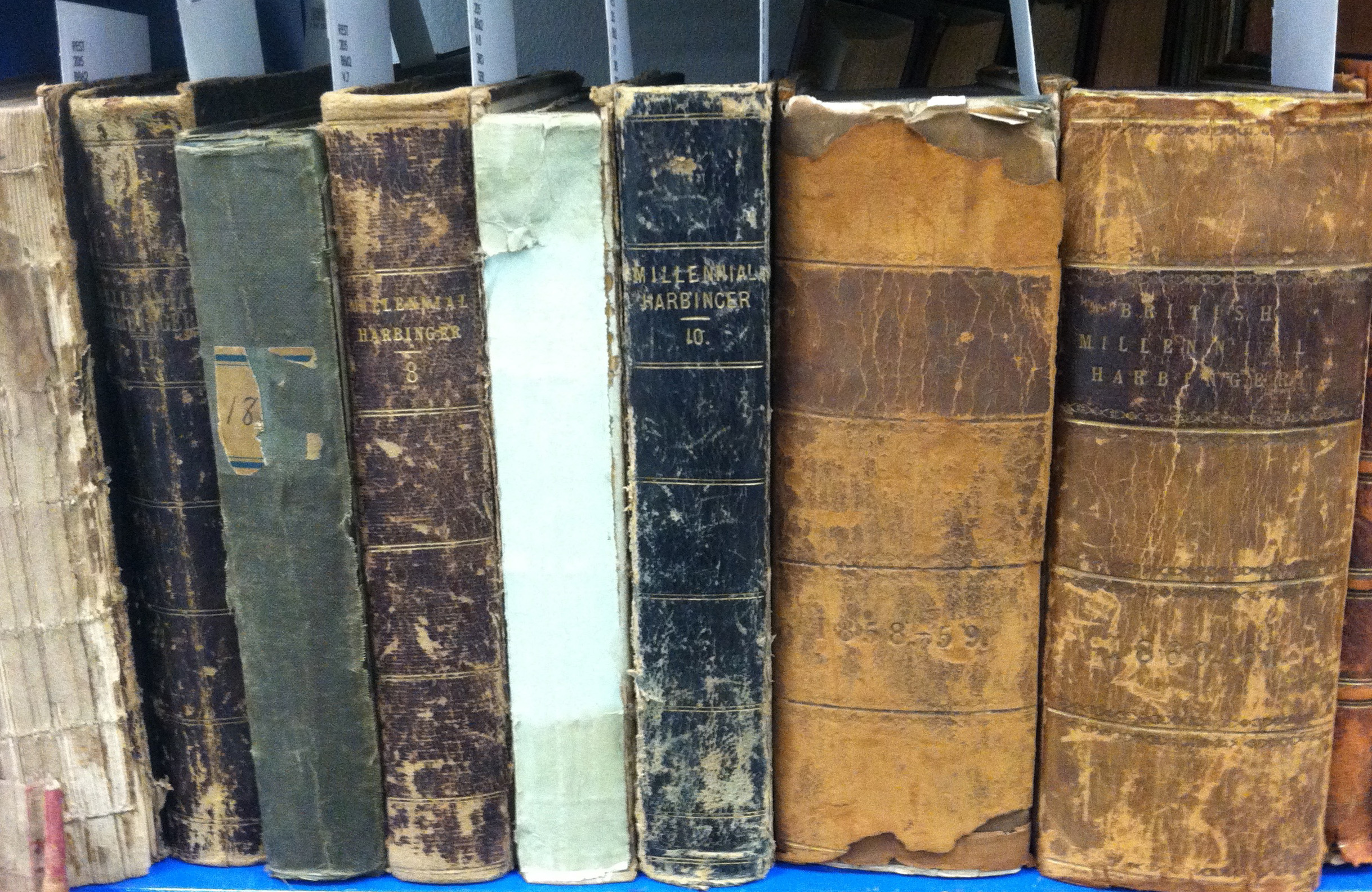

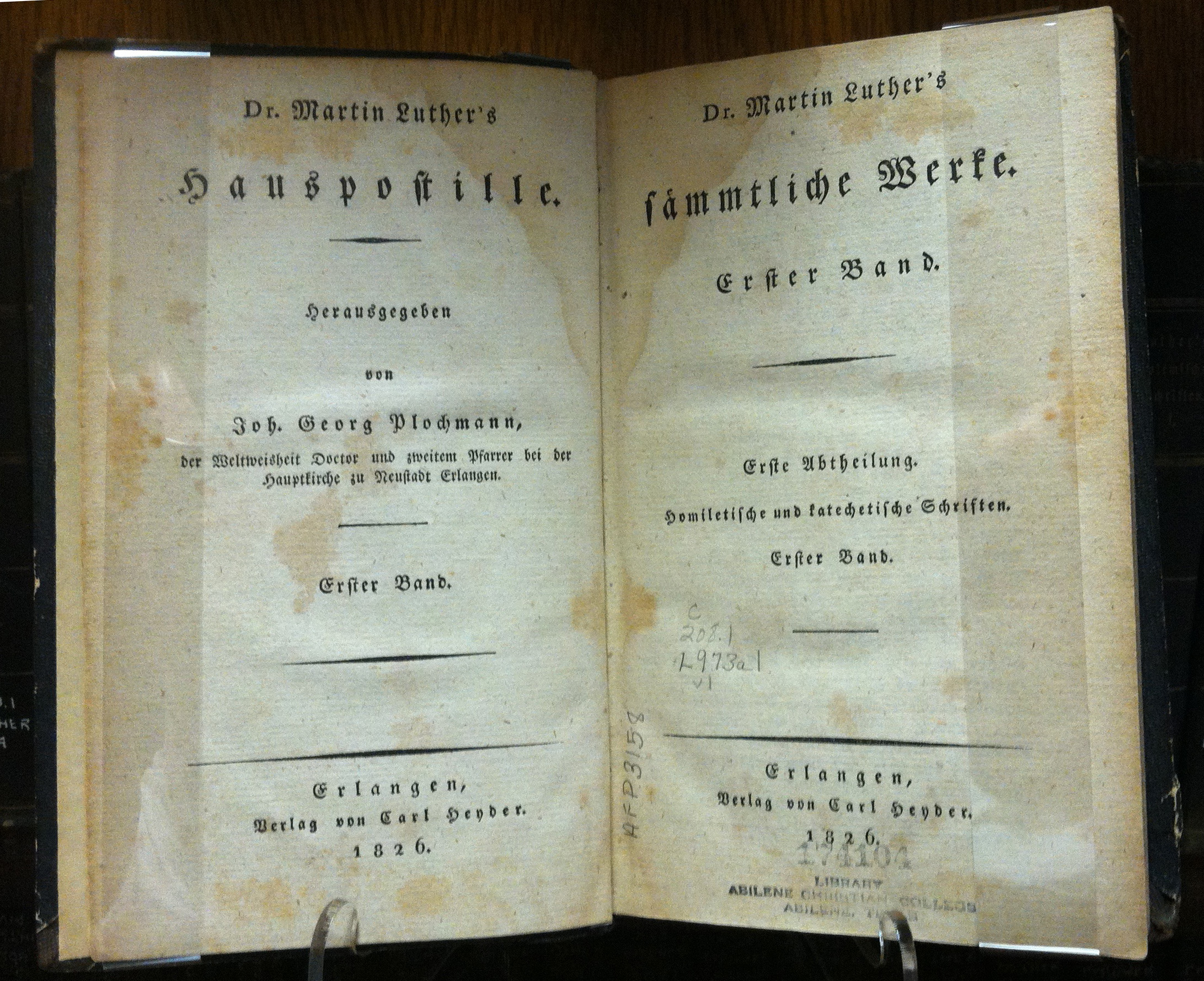

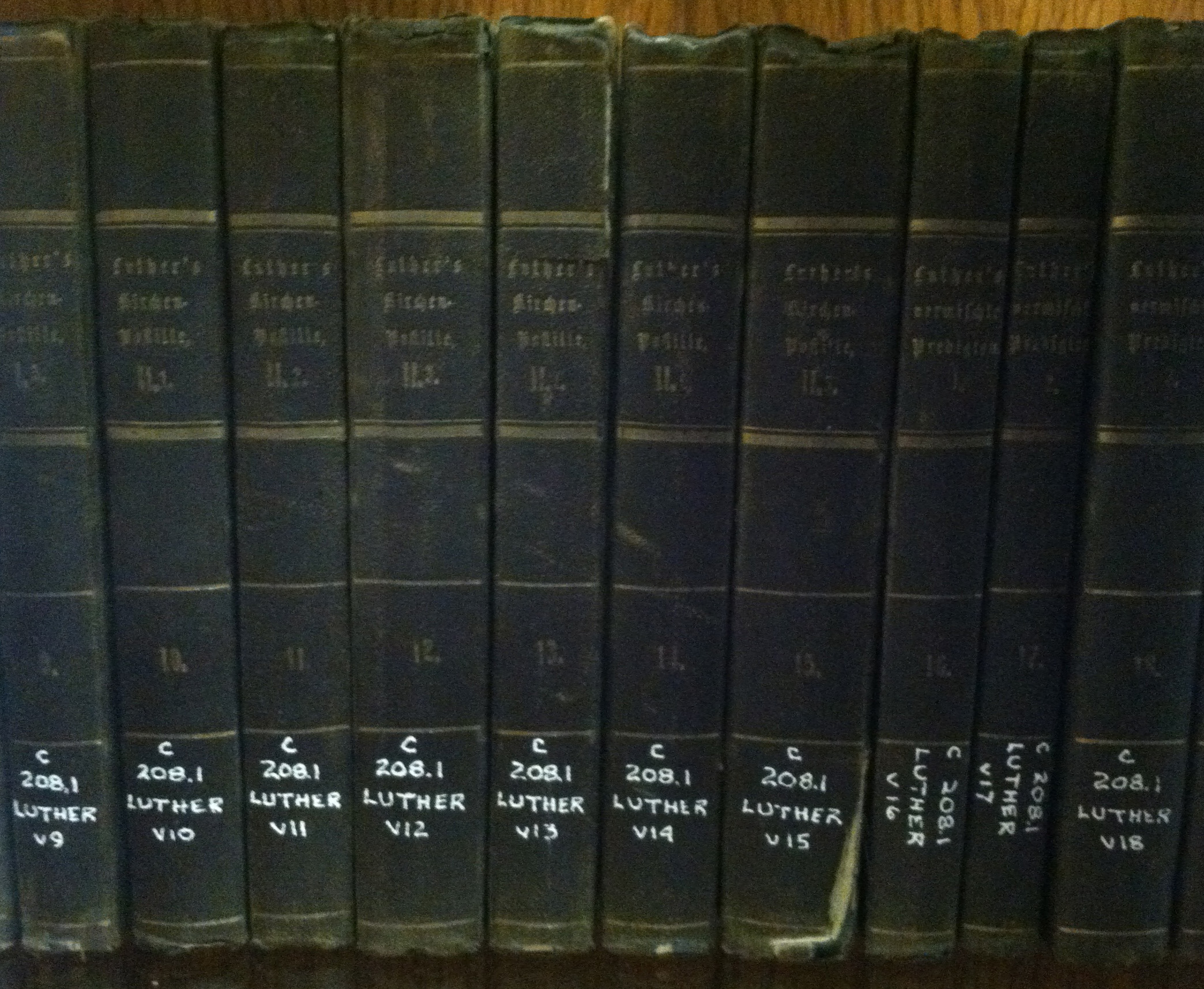

Dr. Martin Luther’s Sämmtliche Werke, 1826-1845

Dr. Martin Luther’s Sämmtliche Werke, 1826-1845

This set of Luther’s works was owned by longtime ACU professor of languages Howard L. Schug who taught Spanish, French, and German. After retiring in 1952 he spent several years in mission work in post-War Germany, continuing a lifetime of interest in missions. The set was published in Erlangen, Germany by Heyder & Zimmer between 1826-1845. Each book contains around 400 or more pages of closely-set type. The six-foot shelf of books indicates the breadth and depth of Luther’s prodigious literary output:

Books 1-15. Hauspostilles and Kirchenpostiles, or commentaries in the form of homilies

Books 16-20. Vermischte Predigten, or miscellaneous sermons

Books 21-23. Katechetische deutsche Schriften, or his catechetical statements and writings

Books 24-26. Reformations-historische deutsche Schriften, or his history of the Reformation

Books 27-32. Polemische deutsche Schriften, or polemic writings

Books 33-52. Exegetische deutsche Schriften, or exegetical writings

Books 53-65. Vermischte deutsche Schriften, or his mixed writings

Books 66-67. Alphabetisches Sach-Register, or indices

Right case:

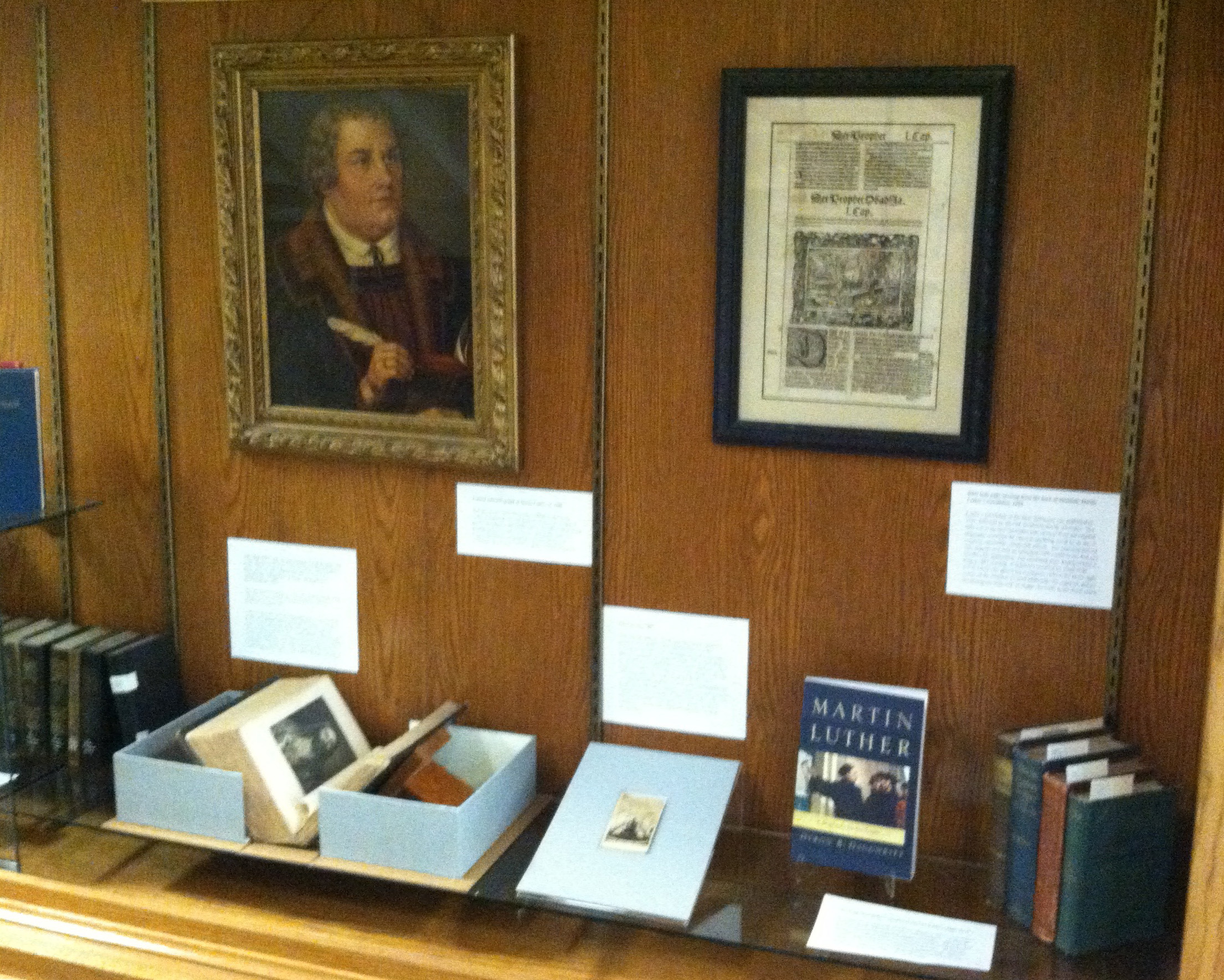

Framed color lithograph of Martin Luther, ca. 1900

With pen in hand and holding either a Bible or other book, Luther is portrayed here with readiness in his eyes. Produced for the mass-market, lithographs such as this reflect the enduring populist interest in Luther. Portraits such as this could have hung in universities, congregations, private schools and academies, as well as in ministers’ studies and private homes.

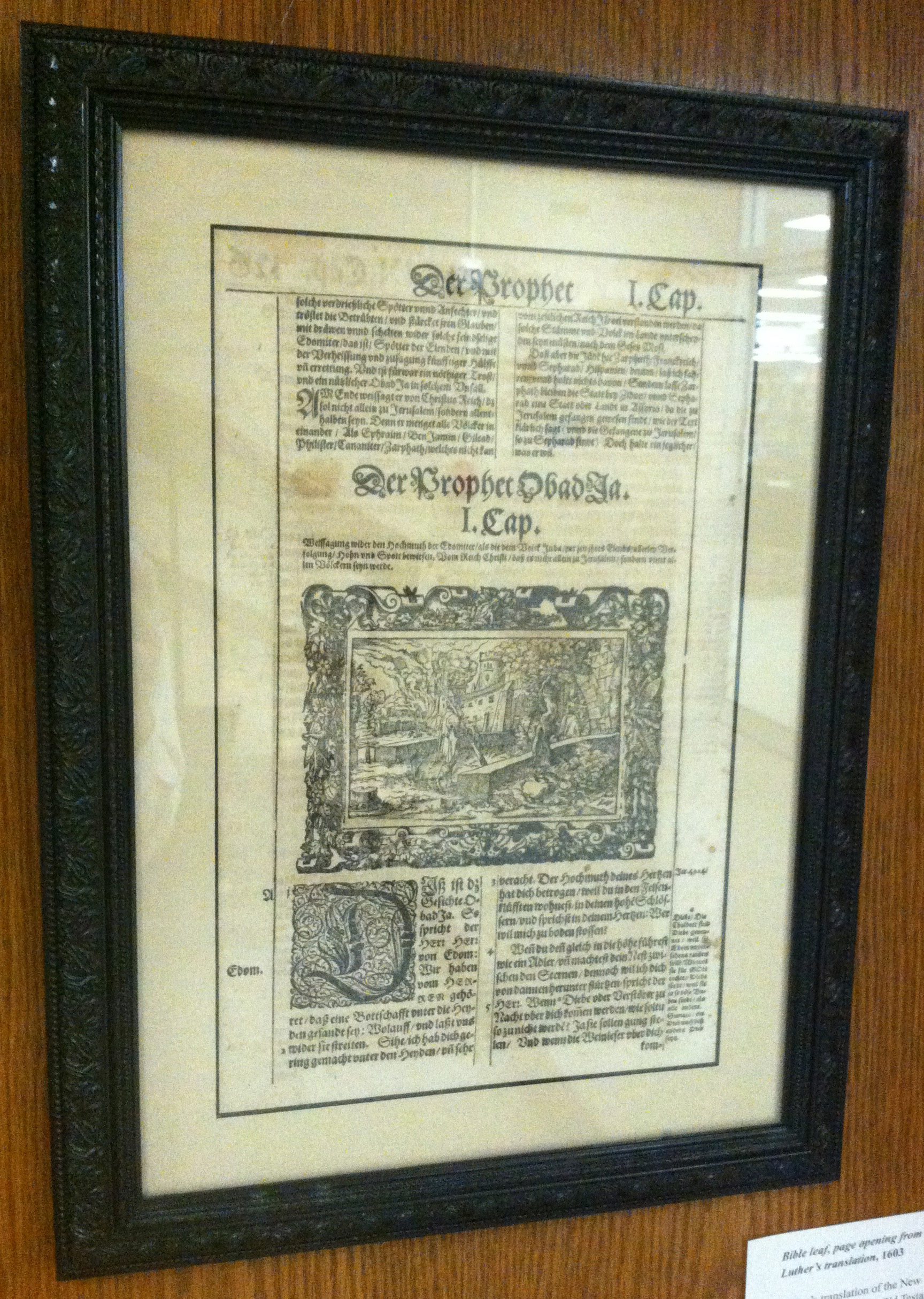

Bible leaf, page opening from the book of Obadiah, Martin Luther’s translation, 1603

Luther’s translation of the New Testament was published in 1521, followed by the Old Testament shortly thereafter. Not only was it the first translation into German from the original languages, it unified the German-speaking world by its use of common, accessible, vernacular speech. The approach proved very popular as it sold an estimated 5000 copies in the first two months after publication. The illustrated page displayed here is from a 1603 printing. It features a woodcut by Virgil Solis (1514-1562) who placed his monogram (VS) in the lower right corner of the woodcut. Conrad Saldoerfer, the engraver, placed his monogram (CS) with an image of a knife in the lower center.

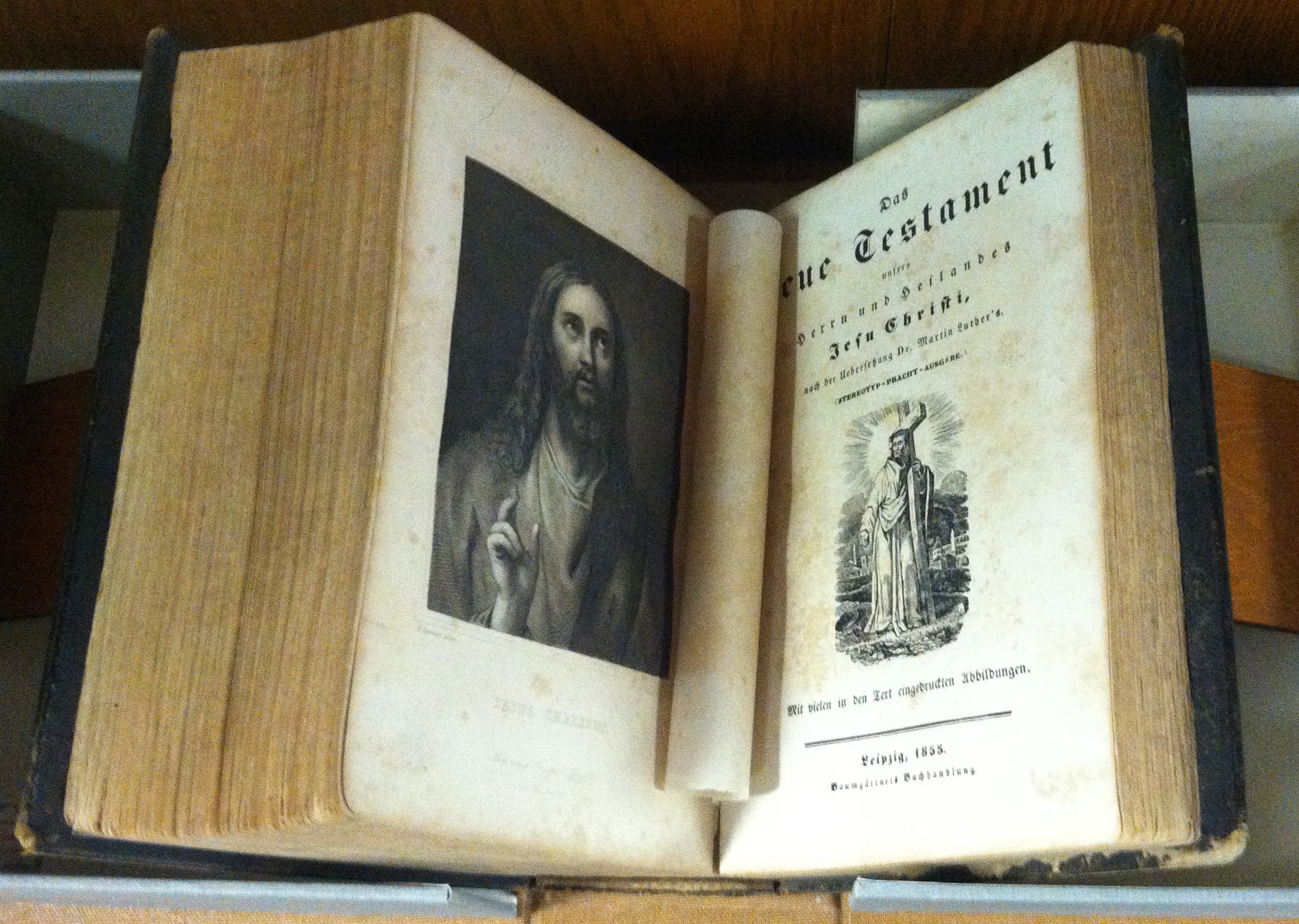

Volks-Bilderbibel, oder, Die ganze heilige Schrift des alten und neuen Testaments/nach der Uebersetzung Dr. Martin Luthers; achter Abdruck, mit 6 Stahlstichen und 532 in den Text eingedrucken Abbildungen. (Leipzig : Baumgärtners Buchhandlung), 1855

The People’s Picture Bible, or, The Entire Holy Scripture of the Old and New Testaments, from Martin Luther’s version. Published in Leipzig, 1855.

Luther’s translation proved an enduring presence well after the Reformation gained solid foothold across Europe. This family Bible is richly illustrated with 6 steel engravings and 532 pictures printed within the text. Displayed here is the title page to the New Testament. This volume is held in the O. C. Lambert Collection. A minister and author among Churches of Christ, Lambert specialized in the critical study of Roman Catholicism.

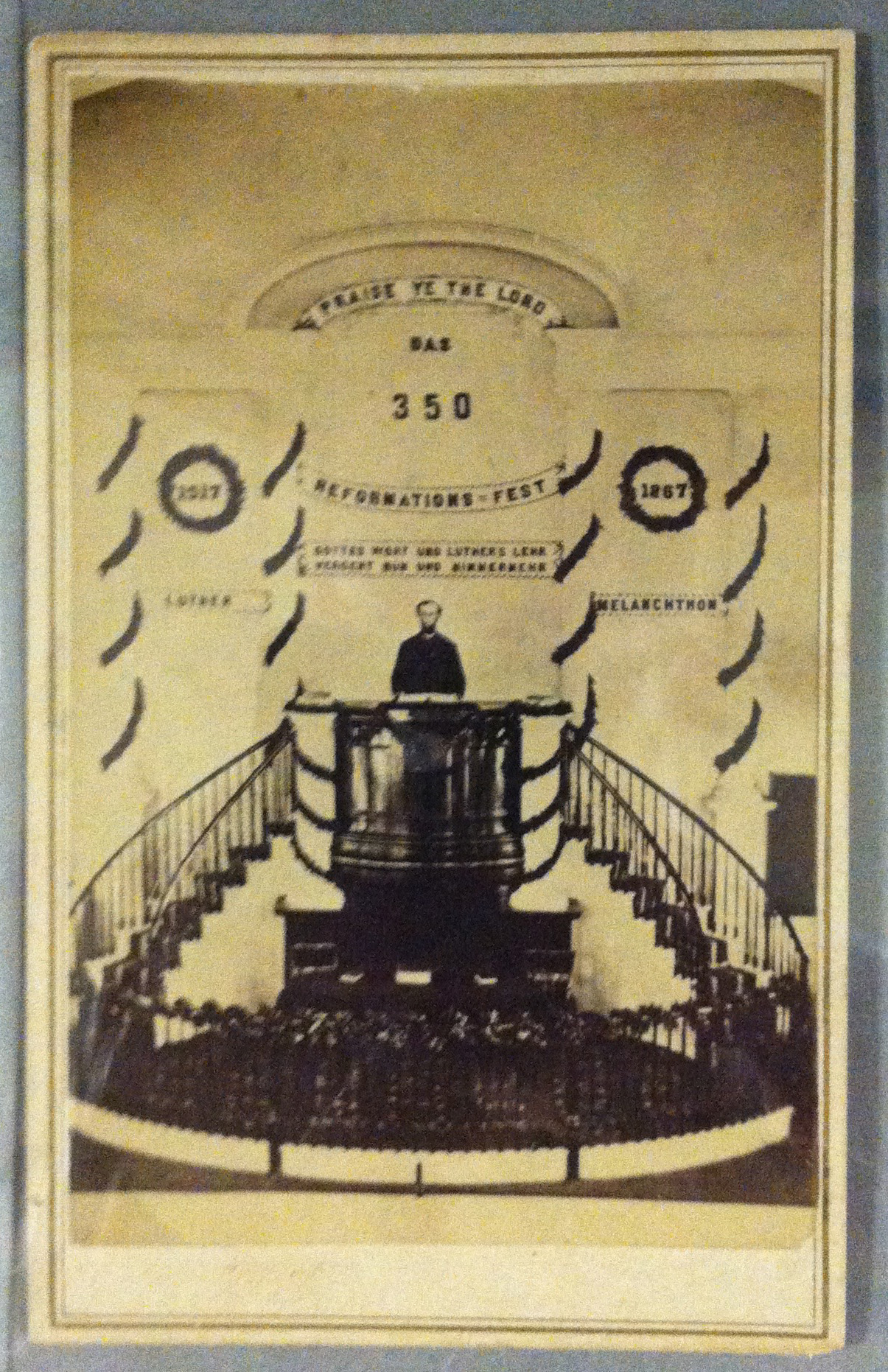

Carte de viste, 1867

This carte de viste (or visiting card) photograph captures a preacher in his pulpit on the 350th anniversary of the Reformation in 1867. The high pulpit, flanked by staircases, is decked in garland. The preacher stands with an open Bible on the stand in front of him; Bibles or hymnals flank him at the pulpit with others on the table below. The banner on the wall behind and above him reads “GOTTES WORT UND LUTHER’S LEHR VERGENT NUN UND NIMMERMEHR” (God’s Word and Luther’s teaching, endure now and ever more). Visiting cards were popular, affordable and widely used. This CDV was published in Belvidere, New Jersey by Peter D. Ketchledge. On loan from Special Collections Librarian McGarvey Ice.

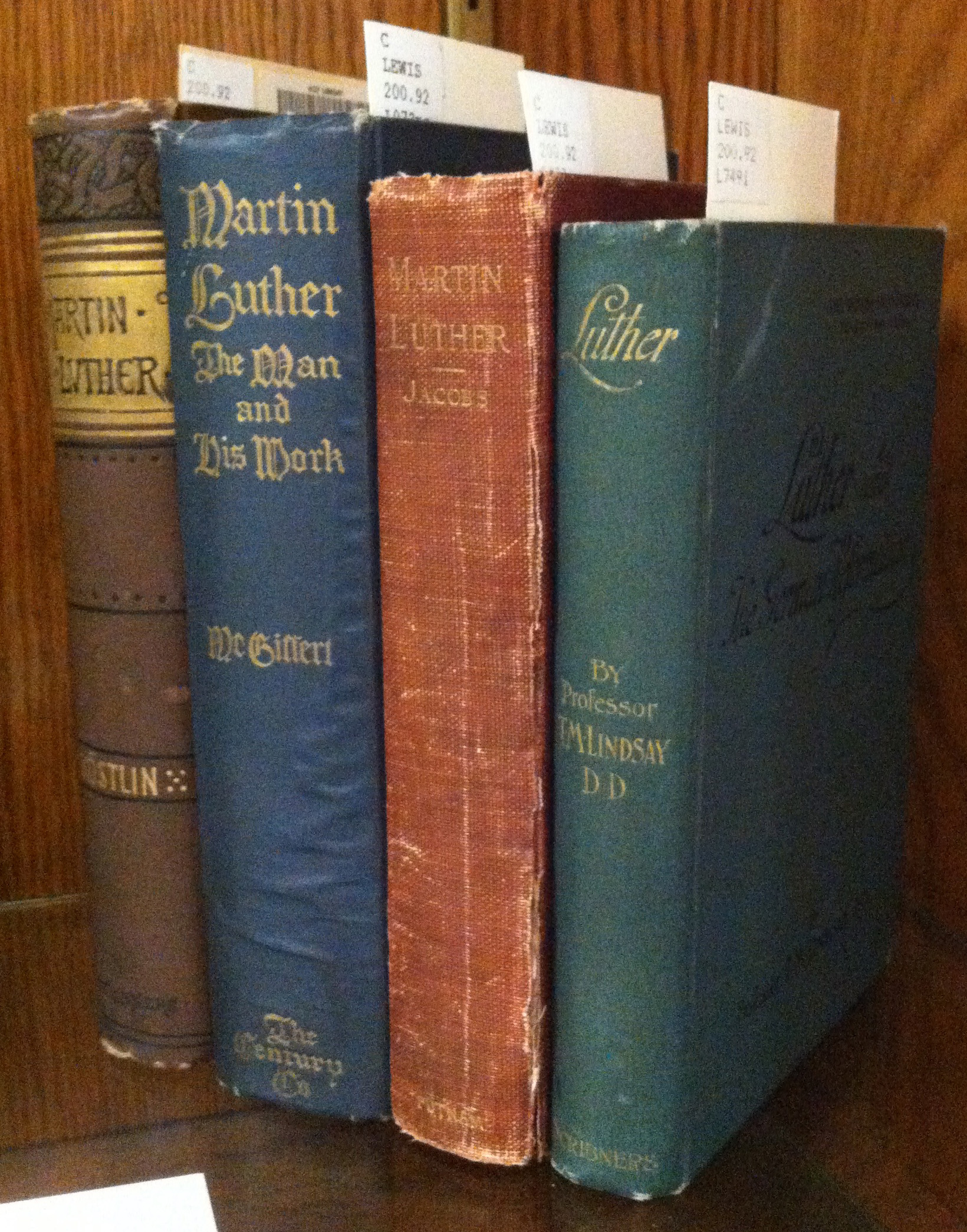

Assorted biographical studies of Martin Luther, 1883-2017

A Worldcat.org keyword search for ‘Martin Luther’ will return upwards of 210,000 items in over 100 languages. Displayed here are selected biographical studies of Luther’s life and work. These items held by Special Collections are from the private libraries of long-time ACU professors Howard L. Schug and LeMoine G. Lewis. The newest biographical study, Dyron Daughrity’s Martin Luther, A Biography for the People was published in September 2017 by ACU Press.

Interested in more? A rich array of stunning Reformation artifacts, artwork, and documents is available online at here-i-stand.com

Interested in more? A rich array of stunning Reformation artifacts, artwork, and documents is available online at here-i-stand.com