We’ve been busy writing finding aids for recent acquisitions and revising finding aids for sets of papers already in our holdings. You can browse all of our collections on DigitalCommons. See something below that piques your interest or could be useful for your research? Get in touch and let us know what you’re thinking about; we’d love to help!

Paul C. Witt Papers, 1908-1970, MS#34 [Revised Finding Aid]

Paul C. Witt was born in 1898. He received his A. B. from Abilene Christian College, his M. A. from University of Texas, and Ph.D. from University of Colorado. He served as chair of the Chemistry department at Abilene Christian College and elder at the 16th and Vine Church of Christ in Abilene. Witt was not a vocational preacher, but he consistently preached throughout his career as an educator. He also published a series of booklets on studying the Bible in English and Spanish. This collection contains notes, outlines of sermons and Bible class lessons, and transcripts from sermons and speeches by Witt and others. It is housed in one box in three series.

Jim Bevis Papers, 1966-2004, MS#63 [Revised Finding Aid]

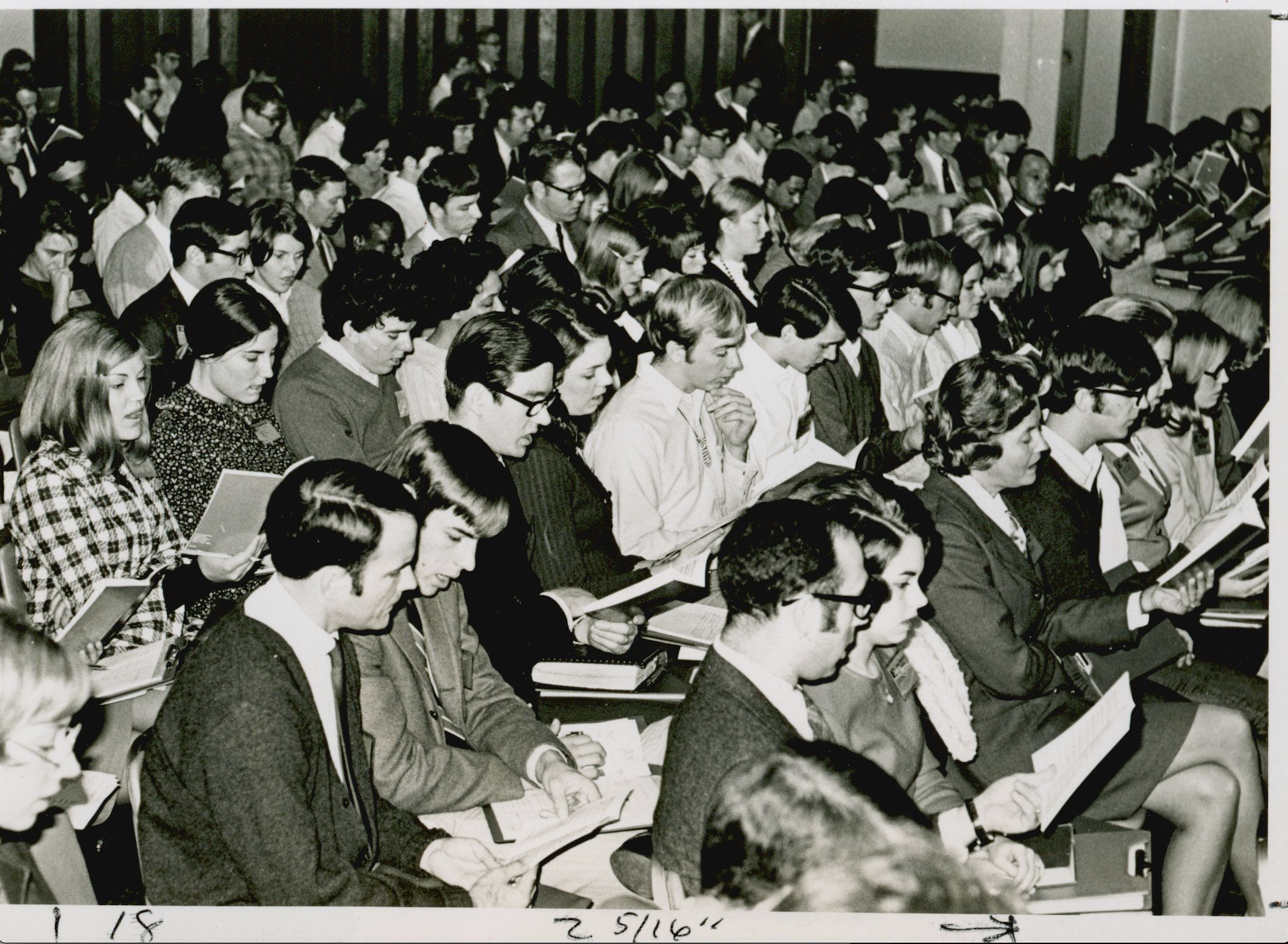

Jim Bevis has been a minister of the gospel for 44 years and has served churches in Lubbock, Houston and San Angelo, Texas, Atlanta, Georgia, Nashville, Tennessee, Indianapolis, Indiana and Sheffield, Alabama. Bevis was a major leader in the Campus Evangelism movement from 1966-1970. With Rex Vermillion he co-directed the Campus Evangelism movement under the oversight of the Broadway Church of Christ in Lubbock, Texas. The movement put forth major evangelical efforts on campuses nationwide, holding conferences with thousands of students in attendance. Despite the support of church leaders, such as E.W. McMillan, M. Norvel Young, Frank Pack, Tony Ash, Reuel Lemmons, the leaders of the movement came under withering criticism. Having lost support from their biggest supporters, and the movement that had focused on teaching about the Holy Spirit, grace, and spreading faith ended in 1970. This collection contains correspondence, photographs of Campus Evangelism events, spiritual renewal conference papers, and newsletters produced by Campus Evangelism movements.

Campus Evangelism photograph from box 4, folder 1 of the Jim Bevis Papers, 1966-2004. Center for Restoration Studies MS #63.

Fowler Family Papers, 1943-1992, MS#495 [New Finding Aid]

Thomas Gideon Fowler, Sr., was an evangelist for more than 50 years mainly in the San Antonio, Texas, area. He was the father of Thomas Gideon Fowler, Jr. (1917-2001) and James Franklin Fowler (1919-1979). James Franklin Fowler preached in Churches of Christ in Temple, Texas; Dallas, Texas; College Station, Texas; Irving, Texas; and Birmingham, Alabama. The papers include correspondence, biographical materials, radio sermon scripts, prayers, newspaper articles, church bulletins, mimeographed and manuscript materials from Thomas G. Fowler, Sr., of San Antonio, TX, and James F. Fowler of Irving, Texas, and Birmingham, Alabama.

Central Church of Christ (Birmingham, AL) Records, 1961-1969, MS#508 [New Finding Aid]

These materials include three folders of correspondence, pamphlets, and other print material related to segregation and integration events at Central Church of Christ in Birmingham, Alabama. Central Church of Christ and West End Church of Christ merged to form Palisades Church of Christ. For more information on the history of these congregations please visit their website.

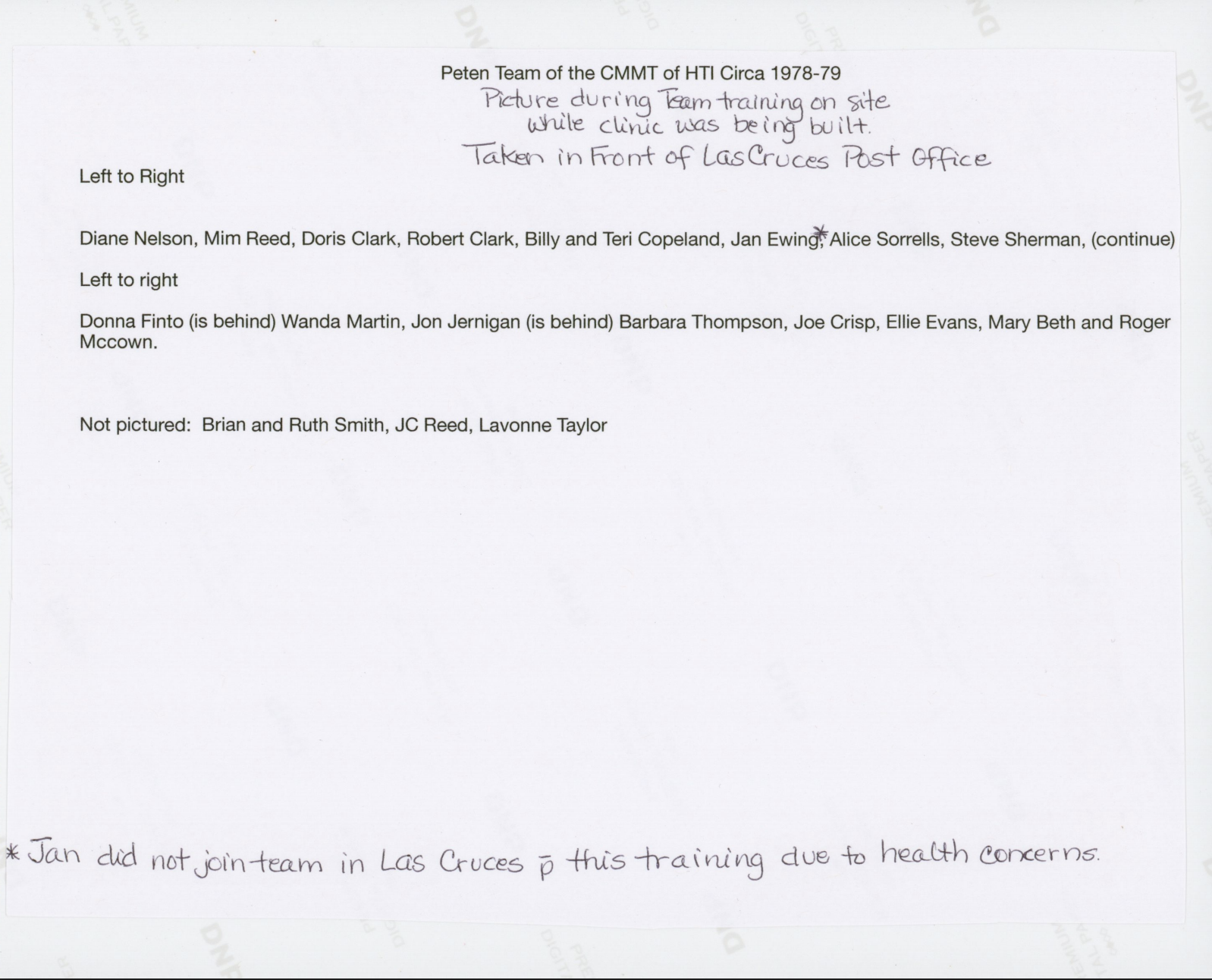

Alice Sorrells Bush Papers, 1976-2013, MS#509 [New Finding Aid]

Alice Sorrells Bush is a registered nurse who is involved with Health Talents International and was a member of the Medical Missions Team in the Peten of northern Guatemala. She currently sits on the board of Health Talents International as part of the nursing committee. These papers include one box of correspondence, training booklets, print materials, and photographs.

Photograph from the Alice Sorrells Bush Papers, 1976-2013. Center for Restoration Studies MS #509.

Back of photograph from the Alice Sorrells Bush Papers, 1976-2013. Center for Restoration Studies MS #509.

Stay tuned for more installments of Finding Aid Round Ups!